South America's cocaine pipeline is always adapting, particularly when the pressure is on.

That pressure, applied in Colombia through an American-backed anti-drug campaign, has had an unintended effect: Colombian traffickers have set up shop in neighboring Venezuela.

This has helped make Venezuela a major platform to ship drugs on to Europe and the United States.

American and Colombian counter-drug officials say that cocaine is increasingly crossing into Venezuela, doubling in the last decade to an estimated 200 metric tons this past year.

Much of it gets into Venezuela through dozens of unpatrolled rivers flowing between the two countries, like the long, Tachira River. Or it travels on short flights from clandestine airfields in Colombia's vast jungle to airstrips just 50 or 100 miles away in Venezuela.

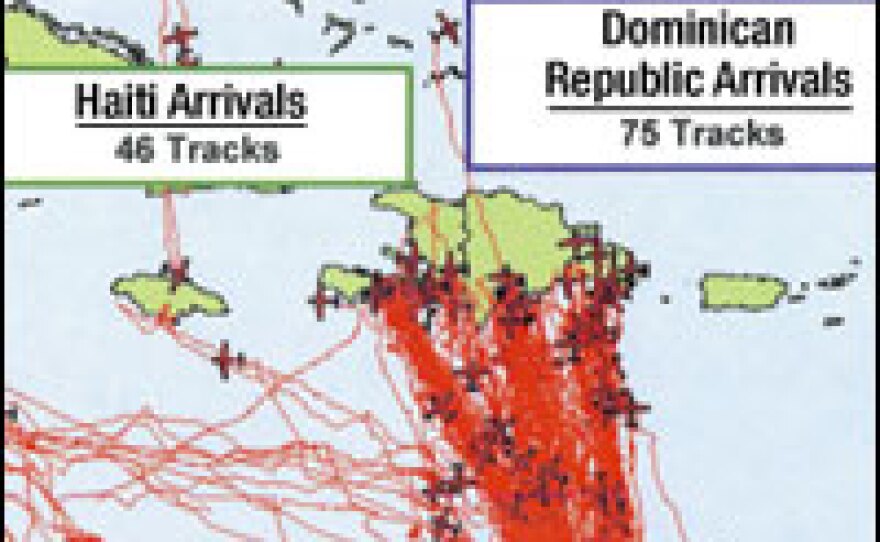

Once in Venezuela, the merchandise is flown out in small planes to the Dominican Republic or Haiti — before the drugs hit American cities. Or they go by plane and shipping container to Europe — and increasingly the first stop of those shipments is West Africa.

The Drug Frontier

A narrow bridge over the Tachira River joins Venezuela with Colombia. The music played on this bridge is all about the frontier — a jagged, porous, violent 1,300 mile border that, for all intents and purposes, exists in name only.

In Urena, Venezuela, people cross the bridge by the thousands, on foot and on rickety motorcycles, past vendors selling chilled juice and listening to radios. They pull suitcases and carry over-sized boxes.

Trucks roll in by the thousands. The inspections are usually perfunctory.

Those lax inspections have permitted tons of cocaine to make its way from Colombia — where most of the world's cocaine is produced — and onto the first leg of an indirect, multi-nation journey.

Gen. Oscar Naranjo is chief of Colombia's National Police. He's a man who has been chasing traffickers since the days when the merchandise of choice were bales of marijuana.

"What we've seen in recent years is a proliferation of routes from Latin America to Africa, Africa to Europe," Naranjo said. "That signifies that the corridor they've tried to use to move drugs goes through Colombia, Venezuela, some African countries and some European countries."

Venezuela's Exacerbated Drug Problem

Anti-drug agencies say complicity by Venezuelan officials has exacerbated the problem.

Venezuelan Attorney General Isaias Rodriguez, in a rare interview, acknowledges that a problem exists.

Two institutions that have had members linked to drug trafficking include the DISIP, Venezuela's intelligence service and the National Guard, which is omnipresent on the border.

"There is complacency or participation in drug trafficking [by those agencies]," Rodriguez says. "And not just them, but civil authorities in airports."

Indeed, one of the key jumping off points for Colombian cocaine is the airport in Venezuela's capital, Caracas. American and Colombian officials say bribes are regularly paid out to airport workers.

They then look the other way. Up to a ton of cocaine is shipped out each month in small planes traveling to the Caribbean or on the many commercial flights to Europe.

Lack of Cooperation

Washington has pumped billions of dollars into Colombia's battle against narcotics trafficking, but the country hasn't won such cooperation from Venezuela's President Hugo Chavez — a populist who is not a fan of the Bush administration.

Chavez frequently derides President Bush on his weekly broadcast. In a recent show, he called him a donkey.

Chavez's government says that the Americans are tarnishing Venezuela by accusing it of being soft on traffickers.

He stopped American anti-drug flights over Venezuelan air space long ago. He also ended cooperation with the Drug Enforcement Administration, accusing its agents of spying.

John Walters, the White House drug czar, denies such charges. He says the lack of cooperation has been a boon to the drug trade.

"When you don't keep the pressure on, it dwells like a cancer where it's not effectively challenged," Walters says. "Right now, that cancer is growing in Venezuela."

Tackling Latin America's Drug Problem

Walters says the pressure by Colombian authorities on Colombian traffickers has been fierce. It's led to some recent raids, like the one in Colombia that led to the arrest of Diego Montoya, who was on the FBI's top ten most wanted list.

Such raids have forced other traffickers to seek refuge in Venezuela. Colombian intelligence believes that Wilber Varela, considered by some anti-drug agencies to be the top trafficker in South America, is hiding out in Venezuela.

One of the most knowledgeable people in Venezuela about the drug trade is Mildred Camero. Until 2005, she was the drug czar for Chavez's government. Though well-regarded, she was abruptly removed.

She now is a consultant on drug issues to the United Nations, the United States and private businesses.

"The problem of drugs has gotten out of the hands of Venezuela," Camero says. "Now the big deals are not done in Bogota. They're done in Caracas because there's an open door. Since Colombia has a defined policy of fighting drug trafficking and the guerrillas, well, they come to Venezuela and do business here in Caracas."

Venezuela's Anti-Drug Efforts

One of the biggest traffickers in Venezuela had been Farid Feris Dominguez — now jailed in Colombia.

Since his capture last year, he's become a major font of information about other Venezuelan traffickers and the officials who help them.

At Combito Prison in Colombia, Dominguez spoke of traffickers being in league with authorities. He recalled how he operated with a Venezuelan diplomatic passport.

Dominguez's disclosures have been passed on to Venezuelan officials. And it has prompted some ousters. The most significant has been of Luis Correa, the country's drug czar until Chavez removed him earlier this year.

Camero says she still sees little commitment in the fight against trafficking.

"There is no political commitment. Why? Because they're not interested because they're getting rich," Camero says. "Now the situation in Venezuela is grave, grave, grave. At some moment, we're going to collapse."

Venezuelan officials counter critiques by saying that they work closely with their British and Dutch counterparts. They say Dominguez, after all, was captured on Venezuelan soil.

Increased Violence in Venezuelan Cities

What everyone does seem to agree on is that drugs and violence have whipsawed Venezuela's urban centers, making some neighborhoods in Caracas among Latin America's most dangerous.

El Valle in Caracas is one of the toughest neighborhoods. By day, vendors crowd streets. Music wafts from boom boxes. By night, 15 violent gangs take over, vying for control of the drug trade.

Mercedes Eloisa Caraballo lost a son on a recent night.

She talks and cries. She recalls with anguish how Deivi Alexander Batista had hoped to play professional baseball. Then gunmen pumped eight bullets into him.

"They called me and I ran out to where he was. I said, 'Don't kill him. Don't kill him,'" Caraballo says. "He tried to get up with the first shot, and one kid said he has to die. And so they killed him."

Colombian officials say there's a lesson in the violence.

Colombian investigators interrogated a leading trafficker, Luis Hernando Gomez, before he was extradited to the United States. Gomez called Venezuela a "temple" of narco-trafficking and said that the Venezuelans had no idea how bad it was going to get.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))