The Mingyong glacier on the Tibetan plateau is shrinking.

Scientists say the plateau is warming almost twice as fast as the rest of China. And the glacier is retreating ever faster, now around 150 feet a year.

These climate shifts are changing the lives of the villagers there — and threatening their futures.

The ethnic Tibetan residents of the small village at the foot of the snowcapped Kawakarpo peak are Buddhist. Nowadays, they may listen to morning prayers on CDs, rather than visit the temple, but belief is still strong. And Kawakarpo, or Meilixueshan as it is known in Chinese — where the Mingyong glacier lies — is one of the holiest peaks of all.

"Kawakarpo is an important god in this Tibetan region," village chief Da Zhaxi explains. "Our forefathers said if this god doesn't exist, we can't survive. If it wasn't for this snow mountain, we'd never have achieved this level of economic development."

That's certainly true. About 50,000 tourists visited the village last year, many of them riding ponies up the steep, rocky trail to snap photos of the glacier. The locals are cashing in: Their incomes have increased 15-fold in recent years.

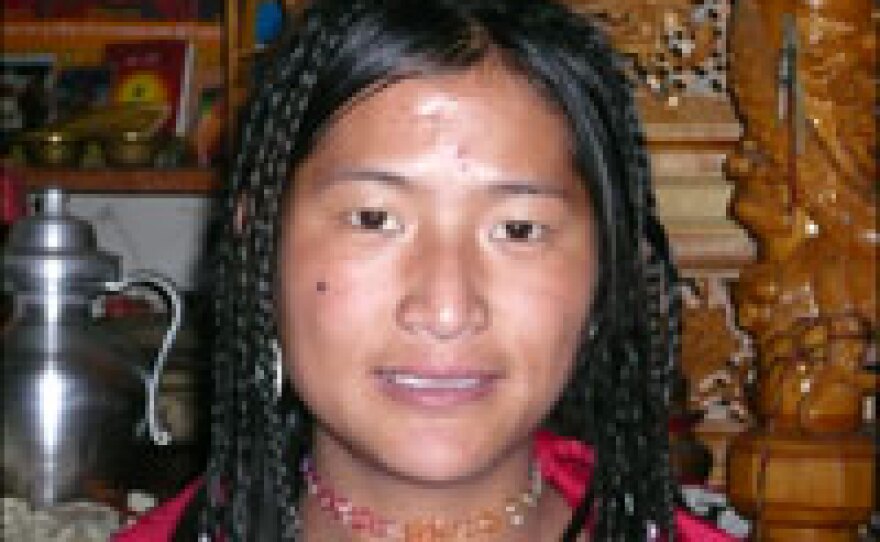

Tibu Zhuoma, 18, works as a guide, but given the glacier's dramatic retreat, she fears for her future.

"I'm very worried," she says. "If the glacier continues to melt like this, the number of visitors will shrink dramatically and that will affect our incomes, and maybe we'll be poor again."

Some Pin Blame on Outsiders

But some of the village's older residents blame those outsiders for the glacier's retreat. Squinting in the sunlight and surrounded by his grandchildren, Anni Zhilei, who is in his 80s, says the glacier's retreat is foretold in legend.

He relates the story of how a visiting foreigner made a model of Kawakarpo and then melted it, thus disrespecting the mountain god. But Zhilei has other ideas. He voices a popular village superstition:

"In the past, there was no electricity. Now we use electricity, which destroys the glacier. Electricity is hot and the glacier is cold, so the two can't coexist," he says.

Extreme Weather Patterns

Livestock is still kept on the ground floors of the village's sturdy wooden houses, but older residents say their lives have been transformed — and climate change has played a part. The river rarely freezes over anymore. They can collect two harvests a year, instead of just one. But warming temperatures have brought pests that ravage their crops — pests never before seen at this altitude. They have also seen more extreme weather patterns, and many, like Kanjug, believe it's a message from above.

"The gods are unhappy," Kanjug says. "We've had floods, storms, mudslides and all sorts of disasters that never happened before. Our crops don't grow well. It's a disaster for farmers."

That view is shared by the area's highest-ranking religious figure, the 14th reincarnation of the Zhaba Buddha, who also sits on a number of government advisory bodies.

"People should respect this holy mountain. But many people shout and laugh upon seeing it, which disrespects the sacred mountain. So there's a problem," he says.

At the Nexus of Change

With the influx of tourists, age-old practices are being neglected. Traditionally, certain areas of the mountain were off-limits to everyone, and the glacier could not be touched. The belief was so strong that the villagers tried to prevent a Sino-Japanese expedition from climbing the glacier in 1991. They failed — and an avalanche buried the climbers, killing 17 people.

The locals believe that this was the revenge of the gods.

Designating no-go areas on the mountainside had benefits for biodiversity and conservation, too. But now, as the glacier shrinks, the sacred mountain's power to protect the villagers is waning.

Ma Jianzhong, a Tibetan working for The Nature Conservancy, says the locals think they are partially responsible.

"One of the reasons, they think, is ... the so-rapid change of the culture, the so-rapid change of the social structure, the so-rapid change of their belief system, especially the young generation," he says.

The small, picturesque village is at the nexus of change, with global warming and economic development transforming the rhythms of life. The glacier's shrinkage could cause ecological catastrophe downstream, and it also threatens the villagers' economic survival and endangers the area's distinctive culture.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))