With food prices soaring and more people going hungry, many developing countries are trying to boost their food production. But it's not enough to grow more food; farmers also need better ways to sell it. Small farmer, meet Wal-Mart.

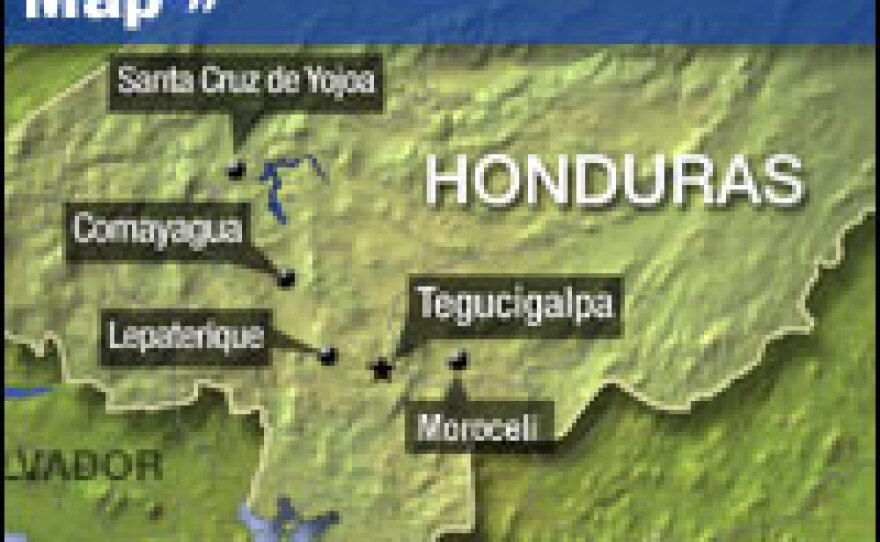

If somebody says "developing-world food market," what comes to mind? Maybe a street filled with fruit, vegetable and meat stands, like one in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras. But another kind of market is taking over in Honduras: the supermarket.

Paiz, one of two supermarket chains in Honduras owned by Wal-Mart, is as bright and clean as any in the U.S. The number of Paiz stores is growing fast. Supermarket sales in Honduras have been increasing by about 20 percent a year.

Luis Alfonso Andino, who's in charge of vegetable shipments at one Paiz store in Tegucigalpa, says the growth is because customers know the food from the supermarkets won't make them sick.

The supermarket revolution, or the rise of national chains selling food with machine-like predictability, is an old story in the U.S. and in wealthier Latin American countries.

But Mark Lundy, a researcher at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture in Cali, Colombia, says in the U.S. the supermarket revolution took about 40 or 50 years to complete. In countries where it's occurring now, he says the time is compressed to 10 or 15 years.

The revolution is happening in China, India and elsewhere, driving big changes that reach all the way back to small farming villages.

Remaking The Model

Increasingly, the key for small farmers' success is to sell to supermarkets. But this means that farmers have to meet some tough new standards.

High in the hills, near the town of Lepaterique, Vicente Sanchez ticks off the crops that his farmers cooperative grows: carrots, lettuce, cauliflower, cilantro. They all go straight to Wal-Mart. Sanchez's cooperative signed a deal with the chain, with the help of a Swiss aid organization called Swisscontact.

"Whatever we plant, we know that it's already sold before we plant it," he says. "Before, we'd plant things without knowing whether we had a buyer, and we used to lose out."

The small farmers have to be careful, because Wal-Mart rejects vegetables that test positive for bacteria or high levels of pesticides.

Ivan Rodriquez, who grew up in a small Honduran farming village, is in charge of Swisscontact's programs in Honduras. He says the safety standards can be a big problem.

"They have difficulties here to meet these standards, because they need specific facilities," Rodriquez says. "For example, to package things here, the best way would be to have a facility that's protected ... against flies, you know, but here we don't have that."

So Swisscontact may help these farmers build a clean, fly-proof packaging room. It's an example of an increasingly popular development strategy to help small, isolated farmers by connecting them to expanding markets.

Developing An Infrastructure

Edward Bresnyan, an agricultural economist at the World Bank office in Honduras, says the deals between farmers and supermarkets help fuel the economy. That translates to better roads and cell phones, so that farmers can find out where they can get the best prices.

For the farmers in Lepaterique, it's working pretty well so far.

Some of them arrived at the Wal-Mart supply center in the outskirts of Tegucigalpa driving a pickup truck loaded with broccoli, green beans and carrots. Wal-Mart manager Gabriel Chiriboga looked pleased.

Within 24 hours, shoppers will see those vegetables on supermarket shelves. And some of the money that they spend will flow back to the small — but well-connected — village.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))