Hours after Pervez Musharraf announced his resignation as Pakistan's president, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice praised him as "one of the world's most committed partners in the war against terrorism." But the former general leaves office in disgrace with most of his own people, narrowly avoiding impeachment after nine years of often heavy-handed rule.

Musharraf now faces an uncertain future. Even when he had the protection of the presidency, the 65-year-old leader was the target of multiple assassination attempts by Islamic extremists. Now that he's out of power, he may be forced into exile for his own safety.

The resignation avoids a politically volatile impeachment on charges that Musharraf illegally suspended Pakistan's constitution and imposed emergency rule last November, firing dozens of judges who disagreed with him.

Some Pakistani officials feared an impeachment trial would produce embarrassing revelations about corruption in the government — and about connections between Pakistan's intelligence agencies and Islamist fighters in the country's tribal areas bordering Afghanistan.

Most of Musharraf's power derived from his control of Pakistan's army. As army chief of staff, he seized power in a 1999 coup, and he held on to his position as the country's top general until November 2007. He finally resigned his military post in the face of domestic and international pressure that painted him as a military strongman with no legitimacy as a civilian ruler.

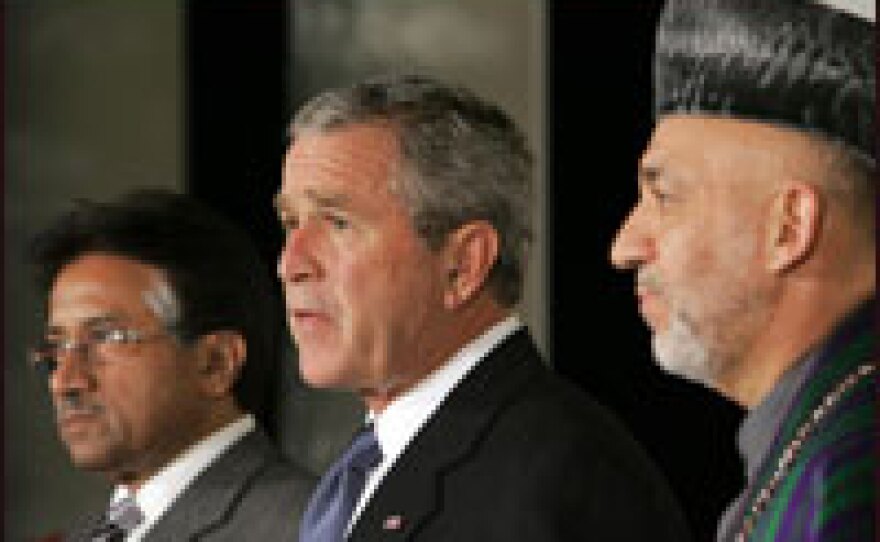

Musharraf ultimately proved unable to control the resurgence of the Taliban and al-Qaida in northwest Pakistan. But he succeeded in convincing the Bush administration that he was the "indispensable man" – the only one who could do it.

'Indispensable' Ally

Few leaders outside the United States have seen their destinies as intimately tied to the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks as Musharraf.

Two years before the attacks, Musharraf had seized power in a bloodless coup. He was largely viewed in the West as just another ambitious general who had muscled his way to the top in Pakistan, a nation that had seen more military rulers than civilian ones in its short history.

But Sept. 11 changed all of that. Suddenly, Musharraf was on the frontlines of America's war on terrorism, with President Bush frequently invoking his name as a key ally in the fight against the Taliban and al-Qaida.

This new role, however, put one of Musharraf's leadership challenges into sharp relief: namely, how to square growing demands from the country's Muslim fundamentalists with Pakistan's tradition of nominally secular government.

This balancing act has not been an easy one for a man whose skills were honed in the military rather than political arena.

A Military Man's Rise to Power

After graduating from the Pakistan Military Academy, the country's equivalent of West Point, Musharraf was commissioned in the elite Artillery Regiment in 1964 and saw action the next year against India in the second of three full-scale wars between the rival nations.

By 1971, when India and Pakistan would come to blows again, Musharraf was a company commander in the Special Service Group "Commandos."

In the coming years, he commanded both infantry and artillery divisions and filled various staff positions. As army chief of staff, Musharraf played the lead role in orchestrating a conflict with India in the rugged mountains of Kargil, Kashmir, in 1999. The handling of the conflict, which brought the two nations to the brink of a fourth all-out war, led to disagreement between the military and the government of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.

The tension between the government and powerful military prompted Sharif to dismiss Musharraf as army chief of staff in October 1999, while Musharraf was out of the country. On Musharraf's return to Pakistan, Sharif refused to allow his plane to land, forcing it into a holding pattern above Karachi airport. But a coup led by generals loyal to Musharraf toppled Sharif's government and allowed the plane to land.

Sharif and his predecessor as prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, were widely viewed as corrupt, and many Pakistanis initially believed Musharraf's power grab marked an opportunity to put the country on the path to stability.

Musharraf also seemed eager to shed the outward appearances of military rule, preferring to appear in public in a western-style suit rather than his medal-clad general's uniform.

Despite Musharraf's early efforts to downplay the authoritarian nature of his rule, it took the nation's Supreme Court, in a May 2000 ruling, to force a return to parliamentary elections. Even so, President Gen. Musharraf maintained a firm hand on the reins of government.

From Pariah to Ally

During the 1980s, Pakistan had been a key U.S. partner in efforts to drive Soviet forces out of Afghanistan. Islamabad was enlisted to funnel American-funded weapons and technical support to mujahedeen fighters, some of whom went on to form the Taliban and al-Qaida, in the fighters' battle to end Moscow's decade-long occupation.

As the Cold War drew to a close, however, Pakistan was increasingly seen as an economic basket case with little promise of political stability. The Musharraf-led coup reinforced the notion. Meanwhile, the economic clout of Pakistan's bitter rival, India, was increasingly on the radar screen of Washington policymakers.

But Islamabad's fortunes were revived by the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and almost overnight, Musharraf went from pariah to ally. Pakistan's cooperation was imperative for any U.S. intervention in Afghanistan, and Musharraf was quick to oblige.

An attack on the Indian parliament building in December 2001, which India blamed on Pakistani militants, brought relations with New Delhi to a new low. The attack was quickly condemned by Musharraf.

The whereabouts of Osama bin Laden also presented continuing headaches for Musharraf's government. Despite intelligence reports that the al-Qaida leader is being sheltered by locals in western Pakistan — a hotbed of Muslim extremism — Pakistan's army has been unable to find him.

Musharraf's alliance with the United States angered religious fundamentalists in Pakistan, some of whom wanted a Taliban-style Islamic government in Islamabad and viewed their president as a puppet of Washington.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))