Scientists have been worried about the West Antarctic Ice Sheet for decades. A new study finds that if it were to collapse, global sea level would rise drastically, though not as much as predicted 30 years ago.

Much of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is vulnerable because it rests on ground below sea level. If warm ocean water gets under it, the ice could start flowing off the continent and into the sea. That ice, and ultimately water, would increase sea levels by a substantial amount. A landmark research paper published 30 years ago concluded that the ice sheet contains enough water to raise global sea level by 20 feet.

"The strange thing about that study is that nobody has really reevaluated the number since then," says Jonathan Bamber, from the University of Bristol in the U.K.

In a study published Thursday in Science magazine, Bamber's group now concludes that if West Antarctica does collapse catastrophically, global sea level would eventually rise by about 11 feet, not 20.

Bamber and his colleagues used new data about Antarctica's geology and were able to refine how much of the ice sheet is actually vulnerable to a runaway collapse. Using radar and gravity data, they have a much better idea of the shape of the ice cap — and the shape of the rock below.

"And what we found was that it's not the whole of West Antarctica. It's about 70 percent of the area that would melt away into the ocean, according to this hypothesis."

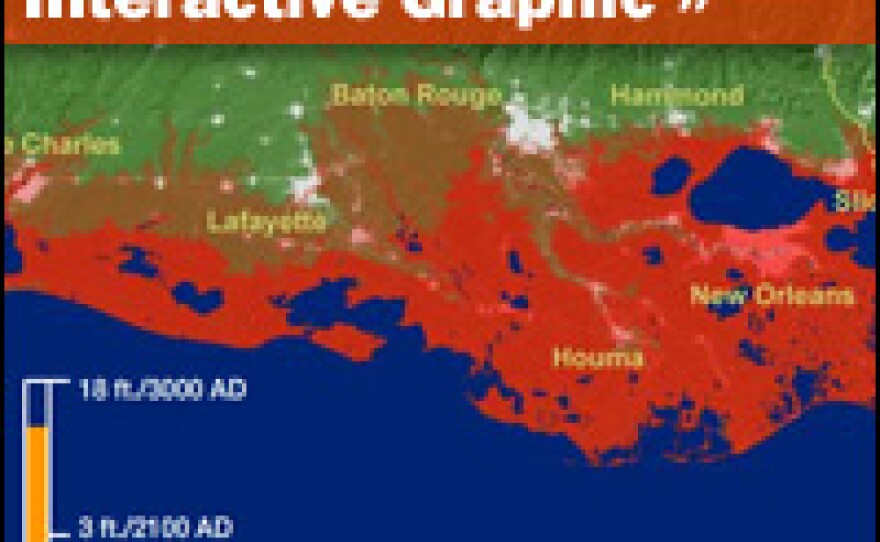

But, sea level doesn't go up the same everywhere. The West Antarctic ice sheet weighs a lot, and that mass creates a gravitational pull that currently piles up ocean water in the southern ocean. If the ice sheet melts, the earth's gravity field will shift and water will flow north. So sea level will rise more on some coastlines, less on others, says Bamber. Still, coastal cities around the world would gradually find themselves under water.

"Global sea level rise is 11 feet. But in some places, it's about 25 percent more than that," he says. "And unfortunately it looks like the Pacific and Atlantic seaboards, of North America at least, are areas where the relative change in sea level is going to be greatest."

A Changing Coastline

So in the long run, U.S. shorelines could retreat more than coastlines elsewhere. But that's the long run, and Bamberg says the "$64 million question" is: How much of sea level rise could occur in the coming decades?

And Bamber has no answer. Neither does any other glaciologist, including Robert Bindschadler at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. But what Bindschadler does say is he doesn't want the new research on the long-term fate of the ice sheet to distract people from the more immediate worries.

"Because it really doesn't change the picture. Decision-makers, the public, they have to worry about this century, or maybe if they're really visionary, the next century. This paper doesn't change that picture one iota."

If the West Antarctic Ice Sheet does collapse, it is likely to take hundreds and hundreds of years. And Bindschadler says the global changes in gravity, which would redistribute ocean water around the world, would take even longer.

"Those won't come into play for many centuries, if not millennia down the road," he says.

Small Changes Could Have Big Impact

And even then, Bindschadler can think of scenarios in which the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could still melt entirely away and still raise global sea level by 20 feet.

Twenty feet or 11 feet, Bamber says, in either case, we can't breathe easy.

"Seventeen million people in Bangladesh alone would be displaced for about a 4-foot sea level rise. So, yeah, 11 feet is just unthinkable," Bamber says.

There are signs that we could be heading gradually in that direction. Two large streams of ice that flow from the Antarctic continent into the ocean have been speeding up for the past few years. Scientists are wondering if this could be the first signs of an ice sheet collapse.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))