India has some stellar educational institutions. The government-supported Indian Institutes of Technology churn out thousands of world-class engineers every year.

The fields of medicine and business have similar elite colleges. Hundreds of thousands more young men and women graduate from colleges and universities just a rung or two below in terms of excellence.

Yet as students toil in classrooms and coaching centers, desperate to get into these elite institutes, even larger numbers of Indian youths barely get a start. Last year, UNICEF estimated that about 8 million Indian children between the ages of 6 and 14 were not in school.

And those that do attend are educated at government-run primary schools like the one in Nandpur Pala, a village just outside the city of Aligarh on the Grand Trunk Road. We visited the school as part of NPR's series of stories on the lives of people living along the route that crosses India and Pakistan.

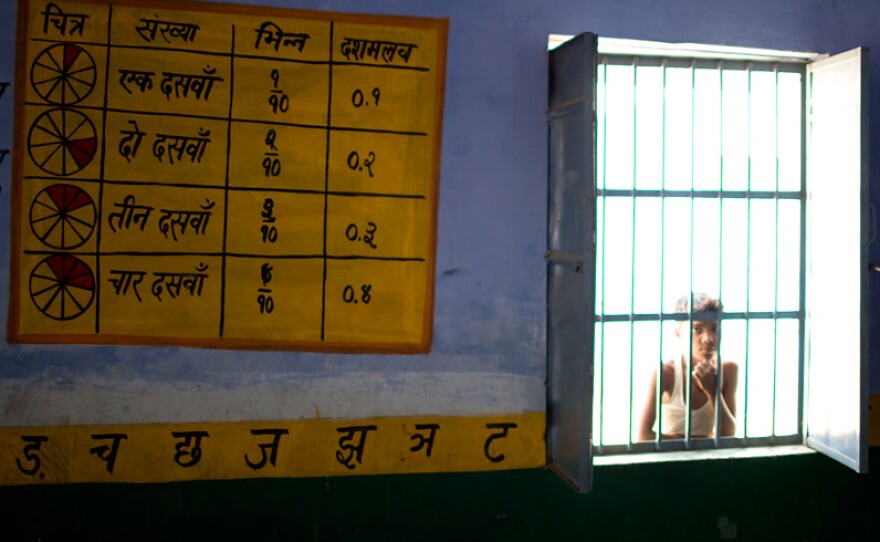

The school has four rooms with blackboards, but no desks, chairs or books. A small courtyard serves as a playground, but no sports equipment is visible. The toilets never had sewage pipes connected to them, so most children defecate in the nearby fields.

There is no electricity. The power line to the school was stolen 10 months ago, and despite repeated complaints, no one has replaced it.

The school's four overworked and underpaid instructors teach 176 students from Nandpur Pala and a neighboring village. The principal, Harswaroop Sharma, a small, wiry man with gray hair, teaches two grades -- fourth and fifth, a total of 62 children -- and runs the school.

He has trouble keeping up attendance, despite the promise of a free daily meal for the students. Only 35 of his fourth- and fifth-graders showed up the day we visited the school.

"They're children of poor farmers. They help out in the fields. Most disappear during harvest season," Sharma says.

Given the often desperate state of government schools, a lot of parents -- even poor ones -- are increasingly enrolling their children in private institutes. Tuition for the private schools is often outside the reach of most poor Indians -- 1 in 5 Indians lives on less than $1.25 a day. But many want their children to have a better life than the one they have led.

Sam Singh runs a private, all-girls institute called the Pardada Pardadi School, just a few miles from the government-run village school.

It is a world apart. The Pardada Pardadi School has a few dozen classrooms, a playground and a computer lab. Some 80 teachers help educate about 1,200 girls.

Singh, a U.S. citizen, spent his career working for the American chemical giant DuPont. He put all his savings into this school in his ancestral village and says his family thought he had "gone cuckoo" when he set it up a decade ago.

It is not a typical private school. It doesn't charge tuition -- instead, it pays each student the equivalent of 20 cents a days. The students can access the money once they graduate.

The older girls are taught how to sew. The income earned from the sales of the cushions, table mats and bedspreads they make helps cover some of the costs.

Singh admits the condition of the government-run schools inspired him to start his own. "There are no teachers there. It's pathetic," he says. "Hardly anyone goes."

The government school principal, Sharma, agrees. But he believes attitudes are changing.

People in the villages are beginning to realize that education is perhaps the only way out of a desperate future for their child. "They think that if the child eventually ends up with a good job, it'll improve their lives as well," Sharma says.

India's Right to Education Act, passed in August 2009, will also make a difference, he says. The law makes it a right for children up to 14 years of age to get free education.

"Now teachers and administrators have to work harder to make sure everyone is educated. It is the law, after all," he says.

But huge challenges remain: Schools lack basic infrastructure; teaching standards are poor; child labor remains common in India, as does discrimination against girls.

Passing the law is a promising start, but for many living along this stretch of the Grand Trunk Road, change will not come soon enough.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))