A smattering of Yiddish words has crept into the American vernacular: Non-Jews go for a nosh or schmooze over cocktails. Yet the language itself, once spoken by millions of Jews, is now in retreat.

But you don't have to be Jewish to love Yiddish. In Japan, a linguist has toiled quietly for decades to compile the world's first Yiddish-Japanese dictionary — the first time the Jewish language has been translated into a non-European language other than Hebrew.

It was in the hills of Kyushu Island in southern Japan where Kazuo Ueda carried out his impressive and quixotic quest, devoting his life to a language few Jews understand, and even fewer Japanese have even heard of.

Now Japan's leading scholar of Yiddish, Ueda was originally a specialist in German. He stumbled upon the Jewish language while reading Franz Kafka, himself a fan of Yiddish theater.

Ueda was immediately smitten with the language that is written in Hebrew letters, but is a hybrid of German, Hebrew, Russian and other languages.

"Yiddish was full of puzzles for me," Ueda says. "That's what I love about it. Reading sentences in those strange letters — it's like deciphering a code."

A Price For His Passion

Ueda made several trips to Israel, but most of his research was a lonely, solo affair. Isolated from actual speakers of the language, he taught himself, with the help of Yiddish newspapers and literature.

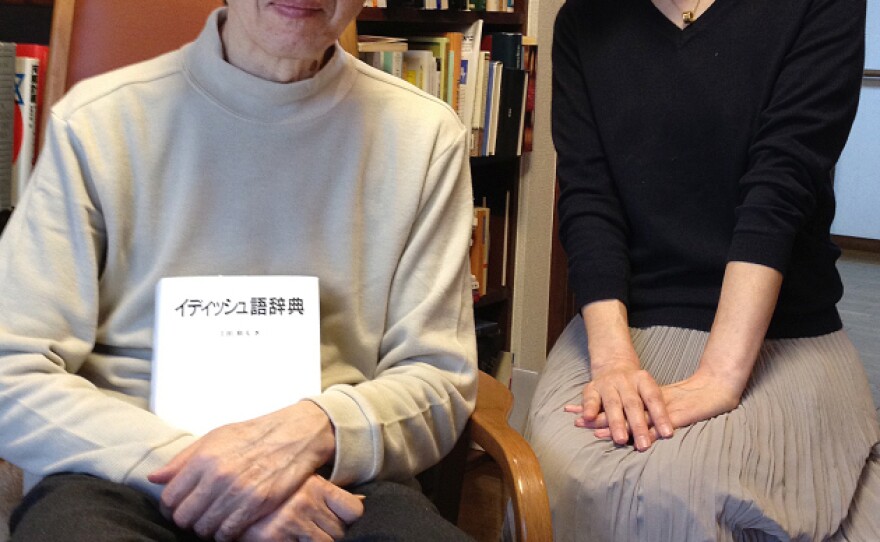

Ueda would later publish a series of books on the Jewish language and people, but he considers that a prelude to his magnum opus — the 1,300-page, 28,000-entry Idishugo Jiten, or Yiddish-Japanese dictionary, published several years ago. His publisher wouldn't release details but conceded sales are most likely tiny for the dictionary, which costs more than $700.

"I actually think $700 is pretty cheap, considering," Ueda says.

Cheap, considering it took 20 years to finish the volume — and that Ueda's doctors say the project may have shortened his life. As his dictionary neared completion, Ueda began to show signs of Parkinson's disease. Now 69, he was forced to retire from the faculty of Fukuoka University in March and struggles to walk and speak.

Ueda's wife, Kazuko, blames years of desk-bound devotion to the dictionary for aggravating his disease.

"Every day, he would sit down to work on his dictionary right after breakfast. He never took any time off," she says. "But for him, this wasn't work but sheer joy. So I thought, this is the way things had to be."

Jack Halpern, a Yiddish-speaking resident of Japan, admires Ueda but says his passion often baffles Jews.

"When Jews hear about Professor Ueda, they say, 'Why?' It's beyond their understanding," he says.

Defying Easy Translation

Just as Japan's population of 120 million is big and affluent enough to support exotic tastes like klezmer music — performed by Japanese musicians — Yiddish has perhaps a few dozen devotees, mostly those who discovered the language via Hebrew or German, like Ueda.

Halpern, himself a linguist and a publisher who used to teach Yiddish in Japan, describes taking a group of his young students on a field trip to New York, where they tried to mix at a traditional Hasidic wedding.

"They saw the Hasidim with black hats and coats, dancing away, and they're all speaking Yiddish to each other. So I approached one of the rabbis there, and I introduced him to this young man who's speaking Yiddish, and he just couldn't understand what's going on; it seemed so out of place for a Japanese person to be in a Hasidic wedding, speaking Yiddish," Halpern says. "It's always amazing to them."

By taking on Yiddish, Ueda grappled with a language that defies easy translation because of its many culturally specific words, like shlimazel, or "unlucky person."

"You can translate it, but you can't translate the connotation, the feeling, around the word," says Halpern. "There's something about shlimazel, that when you say it in Yiddish, it's the right language to say it in."

As for Ueda, who pats his dictionary every night before going to sleep, there are no regrets.

"I wrote it purely for the pursuit of learning," he says. "I don't expect a wave of people to start learning Yiddish."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))