A renowned drug and alcohol treatment program, heralded as a national model for addressing veteran homelessness, is now confronted with widespread drug use and unsafe living conditions that are harming vulnerable residents who come to the campus seeking help with their addiction.

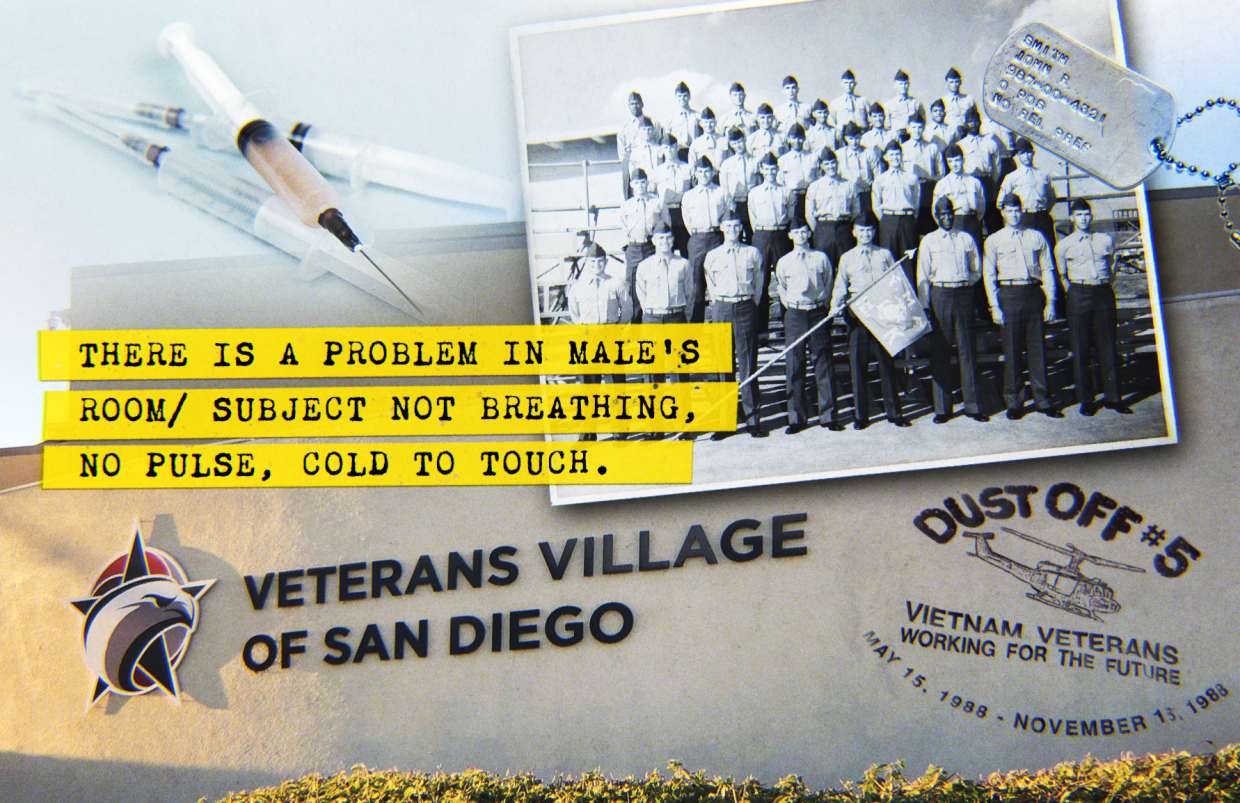

Following several overdoses, San Diego County probation officials took the unusual step last month of pulling clients out of the treatment center and cutting off referrals. The Drug Enforcement Administration is investigating a suspected fentanyl overdose death on the campus. And people who work with other institutions, including the San Diego VA and the county’s Veterans Treatment Court, have expressed concerns about the quality of care provided at the rehab program.

Veterans Village of San Diego has provided counseling, employment, housing and other services for more than 40 years, and it has been lauded by dignitaries and presidents for its approach to tackling addiction and homelessness. In 1988, it founded Stand Down, a multiday event that connects homeless veterans with public services and community support. The event has been replicated in hundreds of cities, endorsed by the Department of Veterans Affairs and featured on “60 Minutes” and National Public Radio.

Employees, as well as residents themselves, have called on public officials and government agencies to address their growing concerns about Veterans Village. There are six complaints about the organization under review by the state health care department. Two lawsuits were filed last year, and two complaints were sent to the Veterans Affairs inspector general’s office in April.

Inewsource spoke with 44 people who have lived or worked at Veterans Village. Almost unanimously, they said they love and support the organization — they continue to believe in its mission and credited the institution with making “miracles” happen — but they are troubled by the conditions at the nonprofit’s flagship 224-bed treatment center on Pacific Highway.

Staff and residents say Veterans Village has deteriorated over the past few years as leadership has prioritized filling beds over providing high-quality care, admitted too many clients during a severe staffing shortage and failed to establish enough oversight to keep the campus drug-free. Photos obtained from residents show unsanitary conditions in the mess hall and bathrooms, and the quality of the food — once a hallmark of the program — plummeted last year.

Big changes occurred in 2018, when Veterans Village started accepting Drug Medi-Cal funding, which now brings in more than twice what the VA pays per day for treatment. It has allowed the rehab center to enroll nonveterans, who are a growing part of the campus population.

The shift has fueled concerns that the organization is disconnecting from its core purpose: to provide a home and community for veterans in need.

As for staffing, a complaint filed with the VA inspector general estimates that more than 55 workers have left the nonprofit — which used to maintain a roster of about 120 employees — over the past 18 months. Many have not been replaced. As of Tuesday, there were 31 job openings listed online.

Emails show Veterans Village continued to admit clients against the advice of VA staff who warned that “service delivery will be negatively affected” by the shortage of workers.

Staff members, as well as residents, said they didn’t feel safe at Veterans Village.

Data analysis by inewsource found that police calls at the rehab center’s address have more than doubled in recent years, from five per month in 2018 to 12 per month in 2022. Reports of violent incidents, mental health incidents and disturbances rose during that time.

According to a police report, an employee was caught last year selling methamphetamine and exposing himself inside the treatment facility. When he was confronted, the staff member took his belongings and left the building. He was not allowed to return.

One resident said the rehab program was a “minefield” for people with addiction. Another described it as “Club Med” because of frequent drug use, or as a third resident put it: “It’s easier to get heroin here than Advil.”

“It’s open here with drugs,” former resident Kevin Huttman said. “You can get them really easily.”

Clients reported seeing fentanyl, heroin and methamphetamine inside the treatment center, and several said they were regularly offered drugs by others in the program. One resident said he found shards of methamphetamine in his room on the day he arrived.

The environment has left residents struggling to stay sober in the face of frequent triggers. A client told inewsource that he smoked methamphetamine for the first time when his roommate at Veterans Village offered it to him. Another said he relapsed on heroin when his roommate snuck out and brought it into the building in the middle of the night.

The VVSD that I was taught (about) and what it was supposed to be was completely different from what I experienced.

The treatment center run by Veterans Village is a closed campus, and clients must stay on the grounds unless given a pass to leave.

Former resident Seth Walters said he managed to stay clean by leaning on the strength of his roommates who were dedicated to their sobriety. But he worried about other residents who don’t have that support — who could be “easily manipulated into using the drug that they’re trying to get away from.”

Walters said clients who use illegal substances on the campus “almost prey on” other residents.

“You’re helpless against this addiction, and you’re sitting here and putting it in front of their face,” he said.

Walters is grateful to Veterans Village for the hard work of the staff and the lifelong friends he has made in the program, he said, but he wished there were more resources available to help residents struggling with addiction.

“The VVSD that I was taught (about) and what it was supposed to be was completely different from what I experienced,” he said.

Former resident Huttman said some clients left the treatment program early, before their housing vouchers were ready, because they “can’t stand it” at Veterans Village. He said the nonprofit had many caring staff members, but high turnover made it hard for him to get the support and services he needed.

“What they promised was we would be going to rehab, given the tools to stay sober and clean, and we would get housing,” Huttman said. “Obviously they’re not fulfilling that promise.”

Employees said the worker shortage had been driven by a lack of support from leadership and concerns about the quality of care provided to residents. Several called the work environment “toxic.”

The day after inewsource and Veterans Village leadership were scheduled to have an interview, the nonprofit’s human resources department emailed a media policy to employees, which stated they could not speak with reporters. Staff were expected to date and sign the policy and turn it in.

“As with any policy here at VVSD, if they are not followed, disciplinary action may be taken, up to and including termination,” the email said.

Akilah Templeton, the chief executive officer of Veterans Village, told inewsource that drug use and being under the influence are not permitted at the treatment center. Despite the staffing shortage, she said, services have not suffered as a result and the nonprofit is providing high-quality care to residents.

The San Diego VA and county employees in Behavioral Health Services have recently performed inspections of the campus and did not find evidence that Veterans Village was out of compliance with its contracts, the agencies said.

County spokesman Mike Workman said Behavioral Health Services is aware of concerns about drug use and overdoses at the campus, but he pointed out that these concerns “are not unique to VVSD in light of the services provided.”

After a recent visit, inspectors found ways for the treatment program to “improve their operational oversight,” Workman said.

“We have worked very closely with them to develop a plan to address concerns related to VVSD’s staffing/vacancies, while also identifying opportunities for more thorough documentation and communication protocols,” he added.

Meanwhile, the county probation department — a frequent source of referrals to Veterans Village — removed eight residents from the property in May after a death on the campus. According to spokesman Chuck Westerheide, the step was taken because “we believed it was in the clients’ best interest.”

The department is no longer sending probationers to Veterans Village, Westerheide said, and is evaluating their remaining clients on the campus “to determine if they need a different level of care.”

Templeton took the helm of Veterans Village in August 2020, amid multiple crises and epidemics facing San Diego and the nation. Opioid overdoses and deaths are on the rise across the U.S., the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact the delivery of public health services, and the homeless population in the region is still climbing.

The CEO said she had worked closely with the San Diego Housing Commission and other partners to face these challenges.

“I’m sad that there are individuals who don’t agree with our decision to be a better partner in the community,” Templeton said. “That means housing more homeless veterans. It means providing services to those who have historically been denied access. It means helping the most vulnerable in this community.”

“There are people who do not agree with that, because it’s not always safe,” she continued. “It’s not always pretty. There are risks attached to that. So if I could see anything change, it would be that people would open their hearts and minds to caring for the least of us.”

Accountability

April was a trying month for Veterans Village.

On April 8, emergency responders came to the rehab center’s address to help a man under the influence of crystal meth who was complaining about a fast heart rate.

A week later, police were called to the campus’s address when a man was lying on the ground unconscious next to drug paraphernalia. The incident was classified as an overdose, according to a police report. Minutes later, a second person was found unconscious nearby. Both survived.

Two days after that, former Navy SEAL Nathanael Roberti was found unresponsive in his bathroom at Veterans Village. He was revived with the emergency opioid overdose drug Narcan.

On April 24, police returned to the area following reports of narcotics activity and possible prostitution. An emergency responder wrote that a woman engaging in drug use and soliciting clients was a “CHRONIC PROBLEM TO NARCS.”

Five days later, Veterans Village resident Brandon Caldera, 29 years old, died in his room of a suspected fentanyl overdose. The DEA’s Overdose Response Team quickly launched an investigation.

The DEA could not provide details of the investigation because it is ongoing, a spokesperson said. Typically, the task force tries to determine fentanyl supply sources and collect evidence that can be used for prosecution.

It was four days after Caldera’s death that the county probation department started pulling clients out of the rehab center.

It’s easier to get drugs here than if you’re on the streets. It’s a safe place to use.

Then, a VA staff member advised Veterans Village that one potential client might not be a good fit for the rehab center, “given concerns with that program,” an email shows. The veteran was hospitalized for substance use, and trying to connect with community services after their release.

Former resident Jarrod Brooker said he understood why clients were being redirected away from the campus.

“I don’t blame them,” he said. “These guys are trying to save their lives.”

The former Navy aircraft mechanic wrote an email to a Veterans Village director in December, warning that the program was jeopardizing the well-being of its residents.

“It's been my experience that this is a life or death situation and we are being hung out to dry,” Brooker wrote.

“There's drug use and drug dealing on this campus for 22 hours a day,” he continued, “there was no accountability, no check up and no structure for the clients here trying to help themselves or at least thought they would at one point. Structure is what VVSD had built its reputation on for many years.”

Brooker, who stayed at Veterans Village from June 2021 to January 2022, said he barely interacted with staff, and he relied on support groups outside the program to help him. He considers himself an advocate trying to help other veterans by speaking out about his concerns.

“It’s easier to get drugs here than if you’re on the streets,” Brooker said. “It’s a safe place to use.”

Overdoses and deaths are on the rise inside and outside drug treatment programs, driven by the opioid crisis and the dangerous potency of fentanyl.

In 2016, San Diego County reported 33 deaths from fentanyl toxicity. Last year, there were an estimated 817 fentanyl deaths in the region, though the final data has yet to be released.

According to the California Department of Health Care Services, there were a total of 63 deaths at licensed drug and alcohol treatment programs in the 2021 fiscal year across 1,727 facilities. None of those deaths — which include overdoses, natural deaths and those from other causes — occurred at Veterans Village.

But three deaths have occurred at Veterans Village this year. The first was from natural causes, and the second is still under review by the county medical examiner’s office.

The third was Caldera, the suspected fentanyl overdose case, in April.

If I went through that program now, there’s no way I would’ve made it. That’s what worries me.

The health care department, which provides Veterans Village with its treatment license, said there were six open complaints against the nonprofit, but did not provide details.

State and federal regulations require Veterans Village and other programs to keep their rehab centers free from drugs and alcohol for the safety of residents and staff.

But treatment programs are not expected to be flawless. Like with any rehab center, staff at Veterans Village said there have always been clients who relapse, as well as clients who bring substances into the facility.

The difference now, according to staff, is that a severe employee shortage has made it difficult to conduct the monitoring and room searches needed to keep the campus clean.

“Because of the staffing, one of the big things is you end up so many times just running around, putting out fires all day,” said Steve Duff, who worked at Veterans Village for two years as an office monitor, handling drug tests and room checks. He left his job in August.

“I think it just gets so overwhelming, you can’t hold people as accountable as you did before,” he said.

Duff, who graduated from Veterans Village in 2018, said his life was a “complete miracle” because of the nonprofit. As a resident, the program set him up with clean clothes, a job and legal support that enabled him to live a sober life.

But the program has “completely changed” since then, he said. By the time Duff became an employee, drugs and violence on campus were “the norm.”

“If I went through that program now, there’s no way I would’ve made it,” he said. “That’s what worries me.”

Residents and staff said they have asked supervisors to bring in drug dogs and conduct impromptu campuswide searches — efforts that Veterans Village used to take when drugs were suspected at the facility — but those didn’t happen.

John Laidlaw, Veterans Village’s chief operating officer, said the nonprofit does not remove people from the rehab program without proof that a rule violation occurred, which ensures that there is a fair process for residents. He said staff perform bed checks and monitor the campus, and leadership is discussing best practices for using drug dogs.

“We are monitoring absolutely the best that we can,” Laidlaw said.

Templeton, the CEO, said the nonprofit had embraced harm reduction tactics like offering medication-assisted treatment, which is proven to reduce the risk of overdose. Narcan, a nasal spray that helps reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, has been placed in residents’ bedrooms.

Templeton also questioned whether the firsthand accounts shared with inewsource describing drugs on the campus were truthful.

“That may not be fact,” she said. “Those sound like very extreme examples, and certainly if those types of situations were brought to our attention, is it not reasonable to assume that we would address that?”

A continuum of care

Inewsource obtained the drug test results of one resident before and after they joined the rehab program at Veterans Village. Within two weeks of enrolling, the resident went from having no methamphetamine in their system to testing positive, and the levels of fentanyl in their urine skyrocketed.

The client’s fentanyl levels were even higher when they took a third test two weeks after that.

The results of both tests taken in the resident’s first month at Veterans Village show that norfentanyl — the substance the body breaks fentanyl down into — was listed as greater than 500 ng/milliliter, the highest range the test could detect.

“In a residential program, the levels in their system should be dropping over time because people aren’t supposed to be using in the program,” said Scott Silverman, the CEO and founder of Confidential Recovery, an intensive outpatient treatment program in San Diego. “The environment is controlled.”

In an interview, Veterans Village leadership said 22% of residents tested positive for substances in a point-in-time count conducted in April.

A county spokesperson confirmed that the rate, gathered from a sample of residents, was consistent with the average found across drug treatment programs in the county.

Experts said point-in-time counts didn’t provide clear information on the extent of drug use in a rehab program, because substances can remain in the body for days or weeks after they are used. Plus, some clients who are under the influence find ways to submit clean samples, which can result in undercounts.

“Just Google how to beat a (drug) test and a ton of advice will pop up,” Silverman said.

Silverman, who recovered from drug and alcohol addiction himself, has spent the past 35 years helping individuals and families address substance use. In honor of his work, the city of San Diego declared Feb. 19 as Scott Silverman Day.

The substance use expert said drugs could interfere with a treatment program’s services.

“How do you run a residential treatment program when there are people using drugs while going through the program?” Silverman said. “You can’t. They contaminate the milieu for everyone else. How could you move the curriculum forward?”

Residential programs are designed to help people learn coping skills and practice new behaviors that reduce the chance of relapse. They are one kind of program offered in a “continuum of care” for people experiencing addiction.

That continuum also includes inpatient programs at hospitals for the highest-needs clients and outpatient programs that allow people to live at home and attend regular counseling.

Each type of program comes with its own expectations and requirements.

Historically, residential treatment centers like Veterans Village discharge clients who relapse. In recent years, government agencies and researchers have discouraged that approach, recognizing that relapse is common and those who experience it still need support.

About five years ago, Veterans Village added a new feature called “Back to Basics,” which allowed residents who relapsed to remain in treatment. But using drugs on the campus still resulted in removal from the program.

“I think using on the campus is usually a hard stop,” said Carla Marienfeld, a psychiatrist at UC San Diego who studies best practices for substance use treatment.

“That would be a reason that that person might not be able to continue in treatment,” she added, “not because of their own relapse, but because their use is significantly impacting the recovery of other people.”

But, Marienfeld said, that doesn’t mean they should be removed from all forms of treatment.

“It just may mean that they might do better or it might be more appropriate for them to have individual treatment or have other types of treatment,” she said.

At Veterans Village, the program director of the veterans rehab center used to have the discretion to remove people who posed safety concerns.

But Shellie Bowman, the former program director who worked at Veterans Village for eight years, said leadership took that ability away from her last year. She was no longer able to discharge residents for rule violations without getting approval from higher-ups who don’t work directly with clients, she said.

Templeton, the CEO, said management was taking a thoughtful approach toward residents who use drugs or are under the influence on the campus.

“Every situation is different,” Templeton said. “Some people are motivated to keep trying. Some people are not. We have to balance health and safety with a desire to see each individual succeed.”

Adjustments

In response to concerns about its finances and vacancy rates, Veterans Village started accepting Drug Medi-Cal funding in 2018. This allowed the treatment center to enroll a wider range of people, including nonveterans, who have become a substantial portion of the rehab center’s population.

Last year, amid a staffing shortage, Veterans Village nearly doubled the number of Drug Medi-Cal beds from 56 to 101. Despite its growing prominence at Veterans Village, the program is not mentioned on the nonprofit’s webpage for its rehab center, and neither is its enrollment of nonveterans.

As Drug Medi-Cal admissions increased, a reduced staff struggled to keep up.

We could howl to the moon until we were purple in the face, and nothing would get done.

Brittany Phillips Hunt, a former associate clinician who provided mental health services to Drug Medi-Cal residents, said she was told that she would never have more than 12 clients at once, but she regularly had more than 15 assigned to her — and at one point she was responsible for as many as 22 residents.

“I made it clear from the very beginning that I needed to be doing therapy in this position, and it was quickly evident that it’s just not possible,” Phillips Hunt said.

Because she was tasked with filling out lengthy paperwork for the Drug Medi-Cal program, residents were only able to meet with Phillips Hunt individually once every three weeks, she said. And that time was spent on conducting required assessments rather than therapy.

Phillips Hunt said she offered regular group sessions to residents, but, without one-on-one therapy, she believed that her clients weren’t getting the support they needed. When she went to her supervisors with her concerns, nothing changed.

“We could howl to the moon until we were purple in the face and nothing would get done,” said Phillips Hunt, who quit after four months of employment.

Clinicians have long been considered central to the work at Veterans Village, because they provide a safe space for residents to address the trauma and mental health issues that may emerge as they tackle their addiction. They are also required roles at Drug Medi-Cal treatment centers.

But therapists, case managers and other employees at Veterans Village have scrambled to fulfill their duties during an intense staffing shortage. At the same time, the nonprofit has also been admitting clients with greater physical and mental health needs.

Kurt Phillips, a former resident, said he was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and spent most of the past seven years in a mental hospital. But at Veterans Village, staff caseloads were so high that he was only able to see his therapist about once every six weeks, he said.

“He was very, very dedicated, but he was also very, very overworked,” said Phillips, who described the staffing shortage as a “major problem.”

Many social service providers are facing high turnover, a problem that has been exacerbated by low pay and burnout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I am not sure what the answer is in the short term, but, in the long term, addiction needs to be treated as a public health issue, rather than a criminal one, and (substance use) counselors need to be paid higher wages, so that we keep people doing this hard work,” said Wendy Wiehl, director of the alcohol and other drug studies program at San Diego City College.

“And treatment facilities need to make sure their employees are practicing self-care to avoid compassion fatigue and job burnout,” she said.

Marienfeld, from UC San Diego, said treatment programs can make adjustments in response to staffing challenges that ensure quality care is still being offered, like by reducing enrollment or cutting back on programming.

“We do our best to maximize things with what we have,” she said.

In April, the VA asked Veterans Village to start an admissions waitlist so case managers wouldn’t have to take on more clients, but the nonprofit declined.

“Service delivery will be negatively affected by going over the client case manager ratio,” a VA employee wrote.

David Skonezny, the nonprofit’s senior director of transitional housing, disagreed.

“We will need to stretch the capacity out of our (case managers) in order to fiscally support the addition of new staff within the program,” he wrote. “I have done a terrific job directing this aspect of the work ... and I would ask for some latitude to direct our staff in the midst of caring for our veterans, which we are clearly doing.”

Veterans Village leadership said they had adjusted enrollment to account for the staffing shortage, and the VA has not mandated an admissions freeze.

Records show that the nonprofit asked the San Diego Housing Commission to permanently remove 40 beds from the rehab program last year “to ensure quality care and positive outcomes for program participants.” The commission approved the request.

Alyce Fernebok, chair of the board of directors for Veterans Village, said the nonprofit continued to operate within required staffing ratios. She said the organization has tried to keep enrollment up, because empty beds are missed chances to help people in need.

“We are looking for opportunities to serve,” she said.

Fernebok, a former Marine, said a board member recently told her about drug use on the campus, but she wasn’t able to track down where the complaints originated.

“Obviously, when it was brought up to me, it’s a concern of mine, too,” she said.

Residents and staff told inewsource that the lack of case managers has made it especially difficult to connect people with housing and employment services. Some clients wait months for seemingly simple tasks to be completed.

When one employee resigned, she sent an email to management that said she was “gravely concerned about the executive team’s prioritization of numbers over people,” adding that she had “seen the quality of the treatment at (the veterans rehab center) experience a noticeable decline due to these poorly set priorities.”

The employee wrote that she had “personally witnessed the pressure to increase numbers affecting staff morale, and firmly believe that this pressure has been the main contributing factor in the increased number of resignations VVSD has experienced.”

Last year, two former employees filed lawsuits against Veterans Village. One accused the nonprofit of denying workers overtime pay and is ongoing. In the other, a former vice president claimed she was fired for requesting family leave. That case was sent to arbitration outside the court system and then dismissed.

The CEO of Veterans Village said she could not comment on the lawsuits, adding that “VVSD does not terminate people for requesting leave.”

In April, a former staff member and a current resident each filed complaints with the VA Office of the Inspector General about conditions at the rehab facility. The office did not confirm if the complaints are under investigation.

“Since the fall of 2020, the quality of the treatment provided to veterans at the agency has deteriorated to the point that it is a dangerous environment for residents and staff,” one of the complaints states.

“The VA needs to stop sending veterans to VVSD,” it says.

Quality of care, quality of life

Those who have lived or worked at Veterans Village said the organization is not fully prepared to meet the complex needs of its residents.

According to the inspector general’s complaint from April, the VA-funded rehab program had not had a nurse since August. The nonprofit’s VA grant states it should have a nurse for nearly 28 hours per week.

The treatment center is not licensed as a medical facility — meaning that it doesn’t offer a full slate of medical services to residents — but a nurse can help with medications, education, infection control and basic health needs.

Danelle Harrington, warehouse donations coordinator at Veterans Village, said the nurse was crucial for the well-being of the residents.

“I don’t think they could run a place without having a nurse,” she said.

In her prior role as an intake coordinator, Harrington said she watched the treatment center enroll people with more complicated medical histories and needs over time who had to be closely monitored.

If I was there right now, do I think I would’ve made it through? No, I think I’d probably have some heroin problem now.

A former firefighter in the Navy, Harrington started working at the treatment center in 2018, a year after she graduated from the program herself. She said she had a life-changing experience as a resident that enabled her to reconnect with her children and address her alcohol use, and she wanted to help offer that experience to others.

“It was a joy to come to work,” Harrington said. “I would come to work and know that God was there with me. It was a purpose and a reason for me to be there.”

Then, residents started coming to Harrington asking for help, because their therapists and case managers were too busy, she said, and drug use was a growing problem.

After she accepted the job in the warehouse, located a block off campus, one client volunteered to help her as much as possible, Harrington said, because he feared he would relapse if he spent too long in the treatment center.

“If I was there right now, do I think I would’ve made it through?” she said. “No, I think I’d probably have some heroin problem now.”

To help fill the gaps left by the staffing shortage, employees said they’d been asked to fulfill new responsibilities that they’re not equipped to handle.

Turquoise Teagle was hired as an outreach coordinator in February, but she said she was quickly told to take on other tasks like performing intakes of new residents and assisting with drug tests. She was expected to train herself, she said, and wasn’t given clear guidance on how to comply with grants or health privacy laws.

“It started to become a snowball, and I was like an avalanche was gonna happen,” Teagle said. “And I didn’t want to be there when it happened.”

Teagle said substance use on the campus was common during her time there, and she has watched clients leave the program because the environment was hurting their chances at sobriety. Residents under the influence of drugs also added a layer of risk for the staff and other clients in the program, she said, because they sometimes acted out aggressively.

According to records and interviews, some staff feared coming to work because they felt unsafe, and at least one person called out sick to avoid being threatened by residents. Hate speech became a repeat problem. And safety measures like adding locks to office doors and installing panic buttons weren’t taken when employees asked.

In May, a resident under the influence of methamphetamine attacked three staff members and left a security guard bleeding from the face, according to a police record.

Teagle, who witnessed the attack, said she “absolutely” felt unsafe at the campus and worried about the safety of the residents, too.

In May, after three months at the job, Teagle quit.

“I truly wanted to do something that made me sleep better and made me feel better inside,” said Teagle, a former member of the Navy.

“My fear is that I’m doing something wrong,” she added.

Residents and staff said they wanted to see Veterans Village succeed, and they hope leadership will take steps to help clients thrive — steps like providing proper training, reducing admissions, supervising the campus more closely and listening to feedback from the veterans community.

“If they would just sound the cry, there would be people coming to the rescue, but you gotta ask for help or think that you need help,” said Ron Stark, president of the San Diego Veterans Coalition and co-chair of the One VA Community Advocacy Board.

Stark said Veterans Village gave him his first job after leaving the Navy, and, without that opportunity, he probably wouldn’t have ended up where he is today. He said he is alarmed by the concerns that have been raised with him about the nonprofit, and he wants to do whatever he can to help.

“I just don’t want it to crumble, because who loses, you know?” Stark said.

“The veterans, who are they gonna lean to? There’s not another VVSD here.”