The San Diego elected official who said the city should stop unfairly targeting low-income and unhoused people when towing vehicles is now pumping the brakes.

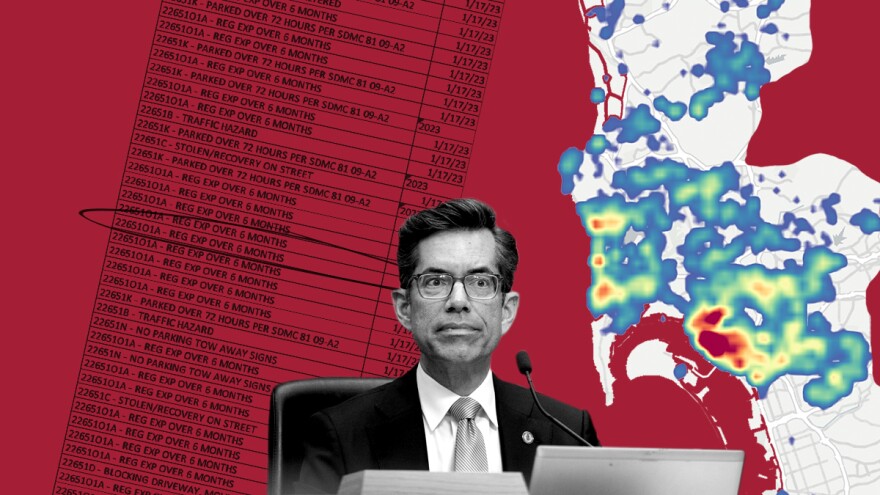

City Councilmember Stephen Whitburn said he would champion changes to the city’s towing program after an internal audit found the most common reason San Diego police impound cars is for what researchers have called “poverty tows.” That includes towing for expired registration, 72-hour parking violations and unpaid tickets — offenses commonly applied to low-income and unhoused people.

But Whitburn recently changed course. He said he wants to await the outcome of a state bill that focuses on ending tows solely for unpaid parking tickets. Two of the three most common towing reasons by far in San Diego are expired registration and 72-hour parking violations.

San Diego’s towing program is costly in more ways than one. The city loses at least $1.5 million a year on these tows because people often can’t afford to retrieve their vehicles. And when people lose their vehicles, they could also lose their jobs, access to education or medical care and, sometimes, their homes.

An inewsource analysis last month found San Diego police continue to order these poverty tows at roughly the same rate — averaging about 650 tows per month — even after the audit raised concerns.

Whitburn, who asked for the audit last year after hearing about financial struggles from people who lost their vehicles for minor violations, called it a “lose-lose proposition” and told inewsource that he would propose changes at a committee meeting late last month. But less than two weeks after the analysis published, he backed off.

In a statement, Whitburn told inewsource that he wants to wait and see what happens in the state Legislature with Assembly Bill 1082. He said it would address some of the concerns he has expressed.

“I want to track the progress of that legislation as a statewide solution would allow for consistency rather than a city-by-city approach,” Whitburn said.

Whitburn represents a district that has seen record highs in unsheltered homelessness in recent months, and he has received criticism as well as praise for ushering in a new ordinance that bans encampments on public property.

He and his spokesperson did not answer questions about what the decision to hold off on local changes to the towing program means for those who face losing their cars in the meantime. Instead, his office encouraged people who qualify to take advantage of state and local assistance programs.

Janis Wilds, an advocate who volunteers with Housing for the Homeless, said Whitburn knows firsthand the struggle of unhoused people living on the street because he accepted her invitation last year to put together and hand out bags of essentials. But she worries that he is allowing politics to come before people.

“I think that he’s very flexible in what he wants, depending on what the mayor wants him to do and what the housed people who have money want him to do,” she said. “There’s the right thing and then there’s the thing that he’ll do if it’s expedient for his future.”

Towing is an important service that ensures public safety, traffic flow and equitable parking. But two out of every five cars impounded in San Diego are related to poverty tows, which have nothing to do with public safety or access.

Struggling to keep your car?

Here are state and local programs, recommended by Councilmember Whitburn’s office, that aim to help low-income residents keep their vehicles current and pay city bills, including parking tickets:

Poverty tows are often linked to higher fees — owners wind up having to pay $1,500 on average to retrieve their vehicles. A recent federal report found one in three Americans don’t have the money to cover a $400 unanticipated expense.

When owners don’t pay up, their vehicles are sold at auction to recoup the costs for towing and storage, but that money rarely covers even half of the expense. The personal loss, coupled with the public cost, is why the city auditor recommended changes to the program.

A spokesperson for the San Diego Police Department, which manages the program, has said towing is largely complaint-driven, coming from high-density housing areas where parking is a premium. The department disagreed with a recommendation in the audit that called on police officials to consider policy changes.

Assemblymember Ash Kalra, a Democrat from San Jose, is sponsoring AB 1082 to prohibit towing or immobilizing a vehicle due to unpaid parking tickets, increase the number of tickets required before the state can place a registration hold on a vehicle and improve guidelines for parking ticket payment programs.

Lawmakers have until Sept. 14 to pass the bill and the governor will have until Oct. 14 to sign or veto it. If adopted, it would take effect Jan. 1.