Dasan Lynch, a junior at San Pasqual Valley High, clearly envisions his future: He wants to go to college, play sports and pursue a career in law enforcement, like his great-grandfather.

That’ll be the easy part. The hard part will be saying goodbye.

“It’ll be like leaving a piece of my body behind,” said Lynch, a member of the Quechan tribe in the southeastern corner of California. “But I know I have to leave if I want to help my community.”

Leaving home can be wrenching for any student going off to college, but for Native Americans like Lynch, the decision can be especially fraught. Not only are they moving out of the family home, they’re leaving behind their unique culture, which in some cases depends on their presence to survive. Yet staying home has repercussions, too: Native communities typically have high unemployment and few opportunities.

The challenges are reflected in the data. Native American students have a college-going rate that’s about half the rate of their peers in other racial or ethnic groups, and only 42% graduated from college within six years, compared to 64% for all students, according to the Post-Secondary National Policy Institute. Among K-12 students, Native Americans significantly trail their peers in nearly every educational indicator.

California is trying to reverse that trend. It funds early childhood programs for Native children and two dozen education centers that provide tutoring and other services to ensure Native students are ready for college. And under Assembly Bill 167, passed in 2021, the state is creating a Native American studies curriculum for K-12 schools, focusing on the unique culture and history of California tribes.

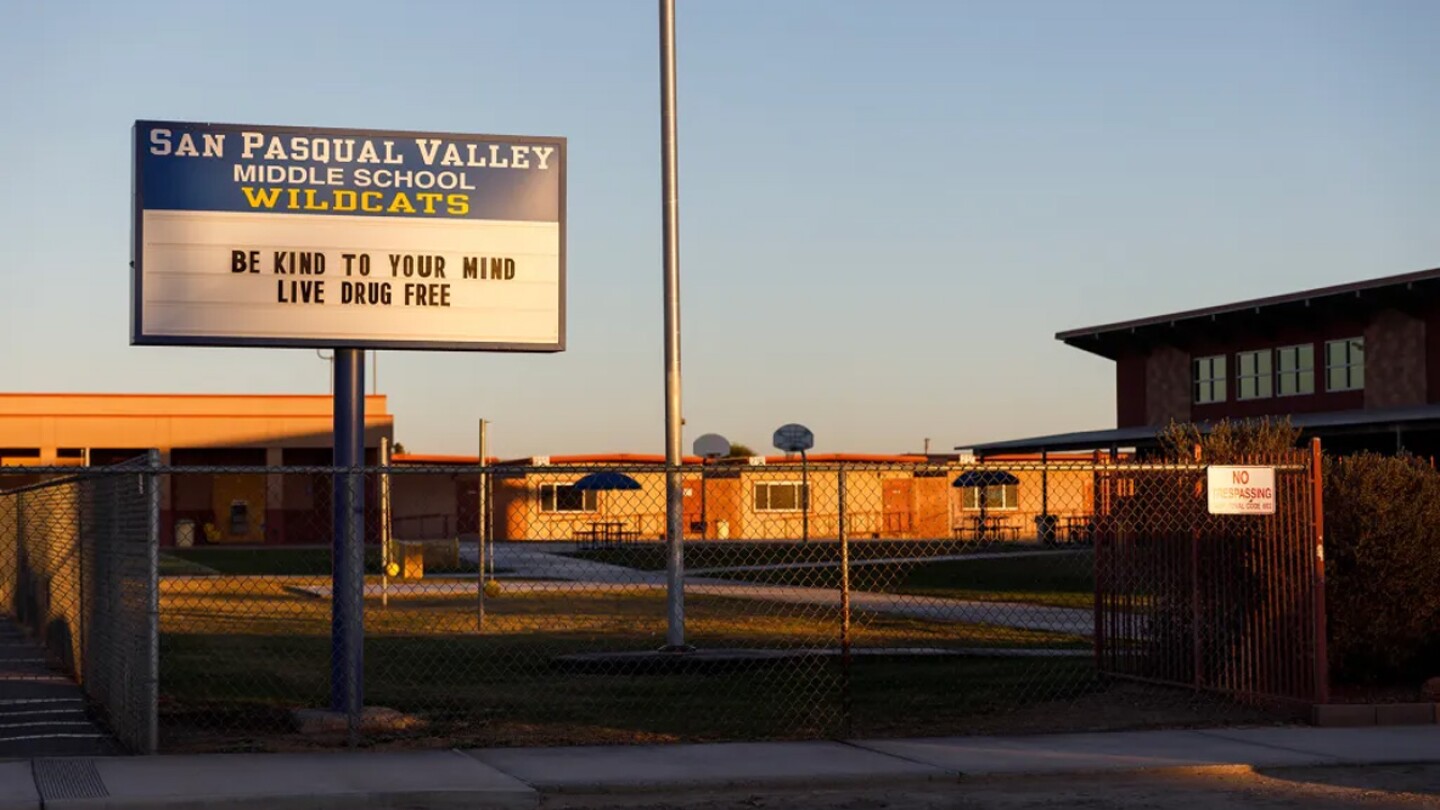

Colleges, tribal education advocates and school districts such as San Pasqual Valley Unified are also working to strengthen support for Native students and build trust with tribal communities. They’re bringing tribal elders to classrooms to teach Native language and traditions, they’re weaving Native American curriculum into subjects like math and art, and they’re encouraging students to go to college — and then return.

“The burden should not be on the students. It shouldn’t be on the families, either. The burden is on us,” said Rachel McBride-Praetorius, a member of the Yurok tribe and Chico State’s director of tribal relations. “We all know the issues and barriers. We need to do our best to remove those barriers so students feel supported. … It doesn’t matter if a school has one Native student or 100, all schools need to do this.”

Building relationships and trust

At San Pasqual Valley Unified, located on the Fort Yuma Indian reservation in Imperial County, about half of its 591 students identify as Native American, one of the highest percentages in the state. That shapes the campus atmosphere, where Native celebrations are part of the school culture, and tribal history and traditions are taught in school. Signs around campus identify numbers, objects and colors in three languages: English, Spanish and Quechan.

District counselors also reach out directly to families to build relationships and address their needs — whether it’s help finding work, getting children to school, finding help for substance abuse or any other impediment to students’ success.

“We listen without judgment, we try to be consistent, we do what we say we’re going to do. If families are upset, we’re willing to take it,” said Rose Meraz, a counselor at the district. “We try to be culturally sensitive, and always stay focused on the child.”

For many parents who are tribe members, those efforts have made a difference.

“They say we have to rely on our elders, but I don’t have many elders. So I’m glad my daughter is learning about our culture in school,” said Venisha Brown, whose daughter is in fifth grade at San Pasqual Valley Unified. “It’s good for her. And now she’s teaching me.”

The school district spans more than 1,800 square miles of desert, scrub and agricultural fields. The daily school bus route stretches from the Colorado River to the Mexico border to the Gila Mountains looming dramatically to the north.

The Quechan are one of a handful of related tribes who thrived for millenia fishing and farming along the Colorado River. Spanish missionaries arrived in the 1700s, and in the mid-1880s, the U.S. military built Fort Yuma on a steep hill overlooking the river to safeguard a crossing used by emigrants. In 1884 the government turned Fort Yuma over to the Quechans, and the hill is now home to tribal offices, a cafe, a store and historic buildings. The town of Winterhaven is adjacent to Fort Yuma, and the three schools in the San Pasqual Valley Unified School District, a gleaming new health clinic and a pair of casinos are within a few miles.

But the injustices of the past are not forgotten. For more than a century, as part of an effort to “civilize” Native children, the U.S. government forced hundreds of thousands of Native children to leave their families and live in boarding schools, where they were not allowed to speak their language or practice cultural traditions. Many suffered abuse and neglect, and at least 500 died, according to the U.S. Interior Department.

Most were closed by the 1970s, but a handful still exist, including the Sherman Indian School in Riverside, which is now run by a local tribe. Still, distrust bleeds into the present day.

“Some families have no interest in supporting the school because their experience was toxic,” said San Pasqual Valley Unified Superintendent Katrina Leon, who is not a tribe member but grew up in the area and did her dissertation on the impact of Indian boarding schools. “We work really hard, and we need to continue to work hard, to rebuild that trust.”

The ‘trauma … is real’

Allyson Collins, a local parent and former financial analyst for the Quechan tribe, is among those who think the school can do more to support Native students — and the tribe should do more to support the school.

“People sometimes roll their eyes when you talk about trauma. But it’s real, it’s there,” Collins said. “There’s a lot of distrust of the government. The school and the tribe need to be partners. Sometimes it just feels like both sides are just checking the boxes.”

Pamela Manchatta, another local parent, would like to see the district weave Quechan traditions into more subjects and bolster academic opportunities for students, such as dual-enrollment in community college. As head of an after-school and summer program at the tribal community center, she tries to provide some of that support directly to Native students.

Working with children in pre-K through 12th grade, she teaches Quechan language and culture, helps with academics and leads activities like Native singing and dancing throughout the year. On a recent afternoon, she used flash cards to teach a dozen elementary students the Quechan words for colors and numbers. The children sat quietly at desks, following along.

Born and raised on the reservation, Manchatta is among those who left for college and work, then returned. It was important to her, she said, to raise her children on the reservation so they’d absorb the Quechan culture.

“Me and my husband knew that moving back was going to be a challenge. There’s less pay and fewer opportunities, but I grew up here knowing the language and culture, and I wanted my children to have that,” she said. “I didn’t want it to be lost.”

Her children and grandchildren all live nearby, and are active in tribal affairs. By passing on the traditions such as bird dancing and the tribe creation story to her family as well as the children in her program, Manchatta feels that no matter what they end up doing with their lives — whether they move across the globe or stay on the reservation — they’ll always know who they are.

“Being Quechan, it’s something you live and breathe. It’s a way of being. You carry it with you everywhere,” she said. “And hopefully, they’ll pass it on after I’m gone.”

Student Dasan Lynch’s great-grandfather is also among those who left the reservation and returned to help the community. Charles O’Brien, a one-time San Francisco police officer, returned to the reservation later in his career to serve as a tribal officer, inspiring his great-grandson to follow the same path.

Returning to the reservation

For Tudor Montague, returning to the reservation was always his plan, ever since he graduated from San Pasqual Valley High three decades ago. He knew he wanted to help his community, so after he moved away to attend University of Kansas and work on environmental policy for tribes in Arizona, he returned to Fort Yuma in 2017. He now runs a coffee roastery and cafe, employing five people and serving as a mentor to others.

The goal, he said, is to boost the local economy, create a healthy place for people to gather, provide job training to local young people and, of course, serve high-quality coffee in an area where it’s not easily available. He also incorporates Native practices into his coffee business by supporting Indigenous growers, using biodegradable materials and buying organic beans when possible.

His cafe, a cozy and clean space at the foot of a hill, is adorned with local artwork and historic photos of Quechan people. Native seed catalogs are scattered on the tables for perusal. An espresso machine hisses in the background, and customers, most of whom seem to be old friends, reminisce and catch up.

He’d like to see more, though. He’d like to see a community garden, where students can learn about Native plants and farming. He’d also like to see students work with tribal leaders to compile books of recipes for beans, squash, rabbit and other traditional foods, farming practices and other Quechan traditions for future generations.

“The language is dying. We have very few fluent speakers left,” Montague said. “But the culture is still here, and it can come back even more. The youth are hungry for it. They welcome it. It’s inspiring to see, and it gives me hope.”

Still, he knows the quandary that young people faces. The reservation might be home, but opportunities are scarce.

“It’s really hard for kids who grew up on the reservation to leave the reservation. It’s a total culture shock,” Montague said. “But it’s even harder for them to come back. … That’s one thing I’m trying to do: let them know it’s possible.”

Undercounted, under-enrolled

California has about 26,000 Native students in its K-12 schools, fewer than half a percent of the overall student population, although that’s likely a significant undercount. Native Americans are often undercounted in official tallies, according to the Brookings Institution, because most are multi-racial and often end up classified as another ethnic group. Some families are also reluctant to identify themselves on government forms.

In California, most Native students are concentrated in the northern end of the state. Schools and universities there are also trying to build trust with local tribes and support Native students academically.

At Chico State, McBride-Praetorius and the staff at the office of tribal relations work to ease students’ transition to college and encourage them to maintain their ties with home, so they feel less conflicted about leaving.

For local Native middle and high school students and their families, the staff arranges regular college visits, dinners and activities to meet current college students, and exposes them to college and career options they might not have known about, such as arts or gaming. The staff also arranges for a few dozen students to attend a weeklong American Indian Summer Institute, held in conjunction with Butte College and UC Davis, which introduces them to public college options in California.

For students already enrolled in college, her goal is to keep them there.

The office recently opened a tribal relations center where students can socialize, study and relax. Each year it hosts a Native graduation celebration and a Native American College Motivation Day featuring workshops and information about college life. Speakers, cultural events and activities with nearby Butte College are among the regular activities for Native students.

The efforts have paid off. Chico State’s six-year Native American graduation rate is 55% — about 10 percentage points higher than the rate for Native students throughout the Cal State system.

Still, generations of trauma create huge barriers, McBride-Praetorius said.

“For our community, education was literally used to take our children, our language, our culture. In a way it’s another genocide,” McBride-Praetorius said. “Given that history, there is a lack of trust. It won’t be easy to reverse that.”

Schools can help, she said, by hiring more Native staff, promoting positive contributions by Native people, and broadening curriculum in all subjects so it includes the history and culture of Native Americans, especially local tribes.

A new Native curriculum

Under a law passed in 2021, California is crafting a comprehensive K-12 Native American curriculum, apart from what’s already included in ethnic studies or U.S. history. The San Diego and Humboldt County offices of education are leading the effort and collaborating with tribes, teachers, curriculum experts and Native American studies professors.

When it’s released next year, the optional curriculum will integrate Native history and culture into all subjects, even math. Younger students, for example, can learn to count using acorns, and older students can learn geometry by studying Native basket patterns.

The curriculum is meant to complement the state’s new ethnic studies requirement, which includes a segment on Native Americans, and the updated fourth grade history curriculum, which focuses less on the Spanish missions and more on the history and contributions of Native Californians.

“While we have a long way to go, the model curriculum is a step in the right direction,” Smart said. “We intend on continuing this work well past 2025 in hopes of developing curriculum as comprehensive and unique as the cultures who are from here.”

San Pasqual Valley Unified’s recent efforts to prepare students for college have shown signs of success. Four years ago, only six students from the high school went on to community college, and none went to either the University of California or California State University. Last year, 22 students went to either two- or four-year colleges, with $136,000 in scholarship funds. This year, 35 students have applied to college and 98% completed financial aid applications.

Hard choices

Karra Johnson, a senior at San Pasqual Valley, is among those who hopes to go to college next year. She’d like to study psychology, inspired in part by the mental health challenges she sees in her community. But she’s reluctant to move away because she’s afraid of losing ties to the culture and her extended family.

“I feel this big responsibility. People are relying on us,” she said. “It can feel overwhelming.”

Henrietta Vasquez, also a senior, echoed Johnson’s sentiments.

“I’ve always wanted to leave for better opportunities. But if you leave, it can be a shock. People don’t always root for you because they don’t want you to leave,” she said. “That impacts me a little but my mother says the chance to overcome generational trauma outweighs the negative impacts. And seeing people come back gives me hope. Someone else did it, I can do it too.”

Their classmate, Dasan Lynch, was born and raised on the Fort Yuma reservation, surrounded by family. He said that leaving — gaining new perspectives and experiences, as well as an education — will be the best way to help his community.

But there is a wisp of doubt.

He’s a little nervous about leaving the reservation, where every road, every home, every vista is familiar and filled with memories. And he’s very close to his father, an undertaker at the local cemetery, who teaches him Quechan traditions and language.

“I’m going to worry about missing things, missing events, missing people,” he said. “I have a strong connection here. But I’m young and I want to explore the world, see what’s out there. Then come back.”

Fittingly, there’s no word in Quechan for goodbye. There’s only nyayu`untixa – “see you soon.”

Data reporter Erica Yee contributed to this reporting.