MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: We've all heard that people make sacrifices to cross into the United States illegally. It is dangerous to cross the border and can be life-threatening to trek across the desert. But migrants and their families often make bigger sacrifices than that. In hopes of making a better life, families are often split apart. An award winning novelist is out with a memoir called The Distance Between Us, about her childhood spent in Mexico away from her parents and feelings of abandonment lingers long after they were reunited. Reyna Grande, welcome to the show. Considering all of the talk about illegal immigrants crossing into the United States, we do not hear much about the families left behind. Is part of the reason that you wrote the memoir to tell that untold story? REYNA GRANDE: Part of the reason I wrote it ñ when we talk about immigration we talk about it as something that can only affect individuals. Immigration affects the whole family unit. That is something that I want to bring out. Telling my story about how immigration affected my whole family and how it broke apart and how my parents and my siblings were affected. The choice to immigrate and long-term consequences of that choice. It basically deals with everything that we gained and everything that we lost by coming to the US. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: The book opens with a scene of your mother meeting to make the trek to the United States. You were four years old? How do you remember that so clearly? REYNA GRANDE: I remember when my mother left it was one of the most dark periods of my life. My earliest memories did not include my father, he came here when I was two years old. His departure did not affect me that much. This is the way that things were. But when my mother left it was very devastating. I remember that. I knew that now, I was completely alone. I had already lost my father to the US and now it was taking my mother as well. It was a very dark moment, and one of the things that I write about in the book is how even though my mother eventually came back to Mexico, she was not the same person anymore. The mother that left me that day ñ I never got her back. She never came back to me. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: Your book does not remember your grandmother too kindly. Do you understand now why she was so stern? REYNA GRANDE: I do. My paternal grandmother was the one who got left with me and my siblings. She was 69 at the time and she was really not in a position anymore to want to be raising kids after she had already raised her own, and on top of that my aunt had also left her with her daughter. My cousin was already there and she was there since she was six years old. And when my aunt left she told my grandma I will not be gone for long, but when we showed up at her doorstep my cousin was already going on fourteen. When my mother brought more children for her to take care of, and my mom said I won't be gone for long, my grandmother knew what that meant. To be fair she was put in the situation where at her age, she was not one to be raising children anymore, but I do not have very nice memories of this grandmother because I felt that she was very unkind. She made us feel that we were a burden in her household. My siblings and I ñ having been left behind by both our parents ñ were suffering a lot emotionally. I think her unkindness made that situation much worse. We were in a very vulnerable place, where we really needed some love and some kindness from our relatives. We did not have that in this household and that just made the situation so much more painful. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: How did you come to the United States? REYNA GRANDE: I ran here from across the border. I was 9 and a half when I ran across the border thirty miles from here. My father was gone for eight years and when I saw him again I was almost ten. It was very traumatic to see my dad because for a long time ñ throughout the years that he was gone I only had a photograph of him ñ and he was in a black-and-white photograph, and when I saw him a remember being shocked that he was actually in color. Not black-and-white, he was brown! My father, he decided that he could not come back to Mexico because of the economy, and he'd found a stable job in LA so he decided to bring us here. At the time he was still undocumented, so the only way to get across was to come here illegally. At first my dad did not want to bring me because I was of the youngest of the kids. He said that we are going to be running across; I don't think you're ready for it. I did not want to be separated from my siblings. They were all I had, so I convinced him to bring us and we took a bus from my hometown and we got to Tijuana. My dad went out to look for us and the next day we set out to cross border. We did get caught the first time by border patrol and we went to TJ and then we tried to go back the second time. The second time is very scary because I actually found a dead man hidden in the bushes and that was when I became afraid of what we were doing, but I still wanted keep trying because that was the only way I could have my family back. By making a border crossing. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: I want to let everybody know that I'm speaking with Reyna Grande about her memoir called The Distance Between Us, in case anybody is just tuning in. You make the point that this book was just as much about being left behind in Mexico as it is about living in the United States without legal status. What is it about that experience that you think most Americans do not understand? REYNA GRANDE: About coming here and having to leave everything behind, I think for me one of the things that I really want people to understand is that coming here to this country is not the end of the journey. You come a long way and made a lot of sacrifices you now have to put your life in danger. It's not over once you get here. You still have to struggle so hard to adjust to your new life, and learn the language, and find a way in the world, and to make your way here. There are so many obstacles that you encounter. One of the things specifically that I address in the book is that the experience of the children and child immigrants does. When they start school a lot of times we focus on the needs in terms of the need to learn the language, and this and that, but a lot of times we forget that people come with ñ these children come emotional baggage. From that experience they are just being reunited with parents who they haven't seen in years, and they have so many things besides learning a language that they have to deal with. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: Make the point in the book about the consequences of leaving children behind, is separation ñ and after writing the story ñ what, it if anything, do you think your parents should've done differently? REYNA GRANDE: I wish they had left us other relatives. I had a very good, nice grandmother. My mother's mother was very sweet, and I wish we had stayed with her. When my mother left I wish it had been with her because she was very kind and loving and she would've made it easier for us to handle that separation. I think sometimes you know parents and a lot of times they don't not have a choice who they're going to leave their children with, but that is something that needs to be considered. Who you leave your kids with, and will they be able to give them that love that these kids need during this time. Another thing is that I feel that sometimes parents do not realize what the children go through during separation because the parents are here working so hard, dealing with so much, and they're working very hard to make money. They forget that it's not just about their struggles, and their pain, but their children are also suffering. One of the things that I hear a lot is that once parents bring the children over, once they try to unify this family, the children come with a lot of resentment. Then the parents say you know you're being ungrateful. They appreciate the sacrifice made but they're not really thinking about the stuff that the children have felt. And I think that just having some conversation in saying that I'm really sorry I had to leave you. I've know you've suffered, let's talk about your feelings. Let's try to understand what the kids have gone through. Instead of just focusing on the fact that well I suffered too, and I made sacrifices, but children do not understand it that way. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: With the current debate of immigration reform, I wonder what you're thinking the role of stories like yours play in that discussion? REYNA GRANDE: I think one of the things that one of my books does is to humanize the issue. A lot of times people hear about immigration, hear from the media or from politicians, and sometimes it can be one-sided. Sometimes they can be just focusing on the numbers and statistics, and for me humanizing the story and providing this story about a family, a family of immigrants and what they've gone through, I feel that kind of evens out the conversation. You can get information from all different angles so that you can have a better understanding of the issue. I think to be able to think about in true immigration in more ways than just the political or economical angles. Also think about the fact these are families that are being affected every single day by immigration. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: You had a troubled relationship with your father, and he died a year before this memoir was published. Did you get a chance to discuss this with him ñ the stories in your book? REYNA GRANDE: I did not have a chance to really talk too much about it with him about my writing. My father was the kind of person that every time I try to bring up the past, he would say why can't you just leave it alone. Why can't you just forget about it and move on, and he never understood that my writing was my way of moving on. He never understood that, and I wish that I had been able to share these things with him because there are some things that were very important to me. And all the writing it really helped me heal, and his way of coping with things was to forget about them. And pretend that they had never happened. My way of coping was to acknowledge them, and say yes this happened and they happened for a reason, and I am here now because of all those things that happened. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: My last question to you. Here in San Diego on Friday, an adventure of the book. Tell us about that. REYNA GRANDE: This is organized as an Old Town Mexican lunch adventure, with the author, which is me. Come have lunch with me at Barra Barra Saloon in Old Town at noon on Friday. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: I've been speaking with Reyna Grande. Her memoir is called The Distance Between Us. Thank you for joining us. REYNA GRANDE: Thank you.

Book Event

A lunch and book discussion with Reyna Grande will be held on Oct. 25, 2013 at noon at Barra Barra Saloon in Old Town. Register here.

We've all heard that people make sacrifices to cross into the United States illegally.

It's dangerous to cross the border, and it can be life-threatening to make the trek through the desert.

But migrants and their families often make bigger sacrifices than that. In hopes of making a better life, families are often split apart.

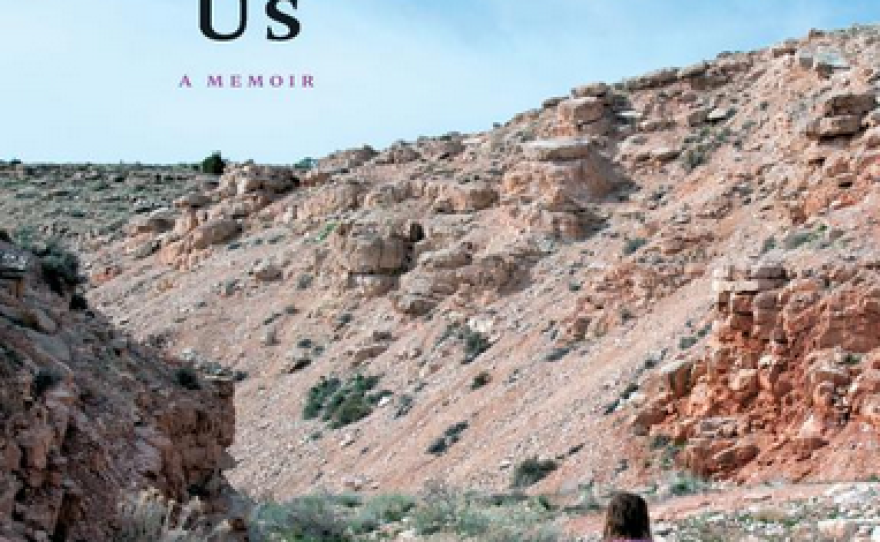

Award-winning novelist Reyna Grande is out with a memoir called, "The Distance Between Us," about her childhood spent in Mexico away from her parents and how feelings of abandonment lingered long after they reunited.

"When I finished the memoir, I felt that at some level, I could finally understand my parents — and forgive them — and that was very healing for me," Grande said.

Grande's father left the family in Iguala, Guerrero for the U.S. when she was just two years old. His dream was to earn enough money to build his family a house.

The reality in the U.S. was different than he expected. When he wasn't able to make the money he thought he could, rather than return home, he sent for his wife. Grande's mother joined him two years later leaving her three children with their paternal grandmother.

Grande is scheduled to discuss her memoir Friday, Oct. 25, at noon at Barra Barra Saloon in Old Town. The public is welcome and registration is required.