California’s middle class is reaching a breaking point. Especially when it comes to the high cost of housing. So says the state’s new governor, Gavin Newsom.

“Housing. This is the issue,” Newsom said at a press conference earlier this month, unveiling his first budget proposal as governor. “Unless we get serious about it, this state will continue to lose its middle class, and the dream will be limited to fewer and fewer people.”

Middle-class Californians could find some relief under Newsom’s $209 billion budget, which includes new spending aimed at getting cities to approve more housing. Other proposals could bring down the cost of health care and higher education for Californians who currently make too much to qualify for state help.

But middle-class California families won’t find much help shouldering other expenses, like the looming cost of caring for aging family members.

What does “middle-class” even mean in California?

In a state where families of four earning up to $117,400 meet the federal government’s definition of “low-income” in certain regions, there may be no definitive answer on what qualifies as “middle-class.”

But according to a recent Pew Research Center analysis of government wage data, families of four in California can be considered middle class if they make anywhere between $59,702 and $179,105 per year.

Direct subsidies in the governor’s budget tend to go toward Californians making less. Newsom noted that no state has a higher poverty rate than California. He wants to try to lower it by giving higher tax refunds to full-time workers earning up to $15 an hour through an expanded version of the state’s earned income tax credit.

He’s also proposing a large boost in spending to subsidize the development of affordable housing for low-income residents. His budget calls for increasing the state’s low-income housing tax credit from $80 million to $500 million per year.

The budget also includes a $500-million bump to the California Housing Finance Agency’s mixed‑income loan program, which finances developments that include units for moderate-income residents.

Housing

The governor’s budget doesn’t propose similar housing subsidies for most middle-class Californians. Matthew Lewis, director of communications for the pro-housing group California YIMBY, said that approach makes sense.

“As a matter of policy, you don’t provide subsidies to people who are making over $80,000 a year,” said Lewis. “But in California, that's the middle class.”

Lewis doesn’t think Newsom can subsidize his way toward a solution to the state’s housing crisis. Instead, he and other housing advocates like what Newsom’s budget does to push local governments to approve more housing in general.

“It appears that Governor Newsom is himself a YIMBY,” said Lewis.

Under Newsom’s budget, cities that meet housing goals set by the state would be rewarded with money from a $500 million state fund, and they could use that money for whatever they want.

“In other words, he’s starting to build funds that would actually financially encourage cities to build more housing,” said Chris Thornberg of Beacon Economics. He said that should help address California’s housing supply problems. “That’s really helpful for California's middle class.”

Newsom has also discussed punishing cities that fail to meet their housing goals by withholding transit funding. It’s an idea that has not gone over well with local governments.

In a statement on the governor’s budget, League of California Cities executive director Carolyn Coleman said her organization was concerned about proposals “that would raid local transportation funds that voters have repeatedly dedicated to local communities.”

Health care

The words “middle-class” only appear once in Newsom’s 280-page budget proposal. They show up under his plan to expand health care subsidies.

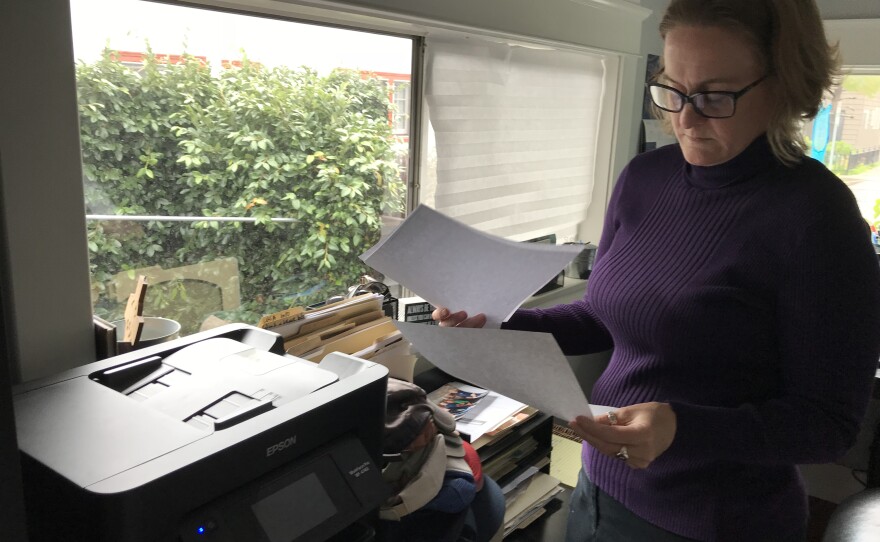

One Californian encouraged by that move is Heather Altman. She works as an environmental consultant out of her home in Long Beach. She gets to be her own boss, and she makes decent money.

“I guess I do consider myself middle class,” Altman said.

She would not have started her business back in 2014 without Obamacare. It meant she could finally afford her own health insurance. She no longer needed to get it through an employer. She has asthma, a pre-existing condition that made individual coverage unaffordable in the past.

Back in 2014, “My premium was $356 for a platinum plan,” Altman said. “I thought that was super affordable.”

Premiums for the same plan have more than doubled, to $761 per month. Altman has switched to a plan with a lower premium. But add in the routine costs of treating her asthma, and she’s spending more than $800 a month.

“That’s very difficult to budget,” Altman said. “And it certainly isn’t sustainable.”

Currently, individuals who earn up to $48,560 a year are eligible for subsidized premiums through Covered California. Altman makes too much to qualify. But Newsom’s budget calls for raising annual income limits for individuals to $72,840 and for families of four to $150,600.

“Had that subsidy bracket been in place when I started my business, there would have been years that I would have qualified,” Altman said. “I’m hopeful that some of these changes may make a meaningful difference in my financial bottom line.”

Altman has shared her story with the advocacy organization Health Access California. Executive director Anthony Wright said Newsom’s budget is promising for Californians like her.

“Current law has cliffs where the assistance runs out,” Wright said. “The extra help will allow some families to get coverage that otherwise couldn’t afford it.”

Newsom plans to pay for the expanded subsidies by creating a state version of the Affordable Care Act’s federal mandate to either buy health insurance or pay a tax penalty (which has gone to $0 under the Trump administration).

In a report on the governor’s budget, the California Legislative Analyst’s Office notes that this approach could create a funding conflict. If the state tax penalty works, it should drive more people to buy insurance. But then, “less funding would be available for premium subsidies.”

College

Higher education is another big drain on middle-class budgets. Newsom’s budget calls for a tuition freeze at state universities, earmarking $300 million for the California State University system and $240 million for the University of California system each year.

University of Southern California professor of sociology Manuel Pastor said middle-class families could also get a break under Newsom’s $40 million plan to make a second year of community college tuition-free.

“If you can make the first and second year free, you’re lowering the cost for a lot of middle class parents of a four-year education,” Pastor said.

The cost of caring for family members, young and old

Universal preschool and six months of paid family leave for parents are still on Newsom’s agenda. But this budget won’t pay for those goals.

Stanford University assistant professor of health research and policy Maya Rossin-Slater said California’s existing paid family leave law could be strengthened. Right now, many parents don’t use it.

Her research shows California workers at smaller, lower-paying companies are less likely to take paid family leave than higher-paid workers. That could be, in part, because workers fear that under existing law, their jobs won’t be protected while they’re out.

“Job protection, I think, is crucial,” Rossin-Slater said, “Especially for middle-class families that might worry about not having a job to return to after the leave.”

Longer paid family leave could help alleviate some of the high cost of child care, which often costs middle-class parents more than college tuition.

California’s population is aging. With more and more baby boomers retiring, the cost of caring for elderly parents will also start to stack up for more middle class families.

The governor’s budget includes a 15.2 percent increase in general fund spending for in-home supportive services. But USC gerontology professor Donna Benton said most Californians don’t qualify for the low-income program. So they’re stuck spending thousands of dollars a year on caregiving.

Out-of-pocket costs eat up 20 percent of caregivers’ income, on average. Some caregivers have to quit their jobs.

“Family members in general sacrifice a lot,” said Benton. “And then when they go to look for services for themselves, usually they’re not going to qualify.”

Benton was part of a state task force that issued a number of recommendations to help ease the cost. Among their ideas was a tax credit for caregiving expenses, as well as more funding for resource centers throughout the state that serve caregivers regardless of income level.

When Benton looked through Newsom’s budget, she said, “I didn’t see anything that, I would say, touched on any of the recommendations.”

Long Beach environmental consultant Heather Altman lives near her parents, who are now in their 70s. She said they’re in a good financial position right now. But she wonders if they’ll end up needing her help in the future.

“Should it come to that time, then yeah, that responsibility falls to me,” she said.

The same will be true for millions of middle-class Californians.