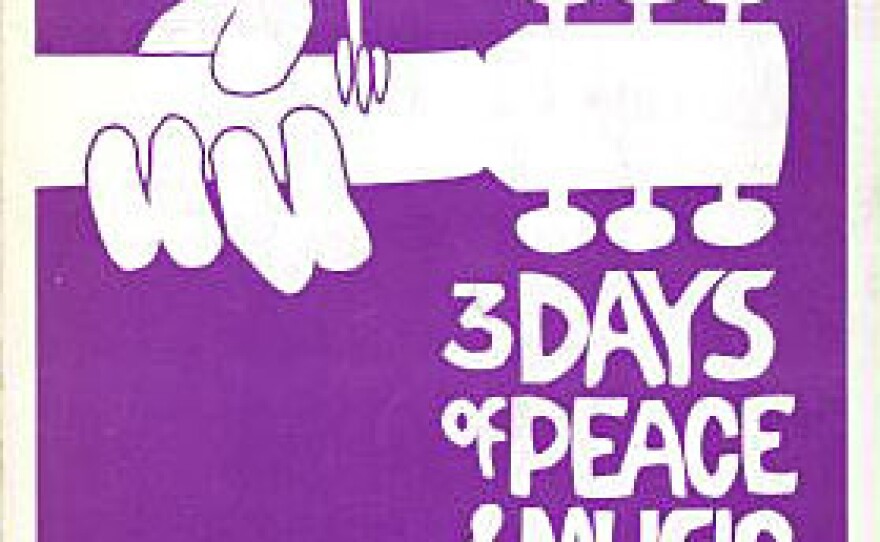

Forty years ago, the Woodstock Music and Art Fair was billed as three days of peace and music. Today, it's being marketed as — well, let's just say it's being marketed.

There's a crowded field of book and music releases. Director Ang Lee has a new film. Target was even offering a line of Woodstock-themed merchandise. The Woodstock name — or do we say brand these days? — has been an unlikely but potent marketing force since the moment the festival ended.

In fact, Woodstock was always intended as a for-profit venture. Though, of course, that's not exactly how it looked in August of 1969. The festival lost a couple million dollars. But the money started flowing pretty quickly. Warner Bros. offered the organizers enough to pay off about half of their debt, in exchange for the movie and soundtrack rights.

It took about another 10 years for the festival organizers to recoup their investment from royalties on movie ticket and record sales. The royalties have been flowing in ever since. The film alone made more than $50 million.

Madison Avenue Got The Message

The organizers of Woodstock weren't the only ones who cashed in on what they'd started, says music journalist Alan Light, a former editor of Spin and Vibe magazines.

"If that's your job, to pay attention to these kinds of trends of movements, this was now a movement you could not help but notice," Light says.

Before Woodstock, most journalists and advertisers had written off the counterculture as something that was mainly confined to the San Francisco Bay Area, Light says.

"I think there was a still a sense that those were those kids. It didn't seem like they were our kids. At Woodstock, that's where people started to think, this is what all those kids are doing, and what they're going to be doing," says Light.

So marketers immediately started using the style and music of young people to sell them stuff, according to Todd Gitlin, author of The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage.

"The conversion of the counterculture into a market was the holy grail of many marketers," says Gitlin.

Take Coca-Cola's 1971 "Hilltop" ad, as it was called. It featured a bunch of attractive, multiethnic, long-haired young people singing together on a grassy hilltop. The commercial was shot in Italy. But the reference to Woodstock is obvious.

Name Recognition

Wharton School marketing professor Steve Hoch says the festival had great brand recognition from the get-go.

"You say the word 'Woodstock,' people are not gonna be thinking about its location," Hoch asserts. "They think about that festival. It happened so long ago, but it's still fresh. It still has exactly the same meaning to people as it did before."

No matter how far you stretch it. This year, festival organizers licensed the Woodstock dove-and-guitar logo to Target for a line of plastic silverware, beach towels and reversible picnic blankets.

So, what accounts for this resilience? Maybe, says author and Columbia University professor Gitlin, it's because we want to remember Woodstock as a moment when Americans could coexist.

"Woodstock ever since has corresponded to that desire, the hope that Americans could quote, unquote come together," says Gitlin. "I'm not cynical about it. I'm not saying it's simply a shtick to sell stuff. What's been projected onto the event of Woodstock is this collective desire, which never quite goes away."

No matter how many times they repackage the soundtrack album.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))