First in a series

In recent years, natural gas producers in the United States have struggled, mostly in vain, to be taken more seriously in the energy world. Big oil companies like Exxon had concluded that natural gas reserves in the United States were not sufficiently abundant to warrant big investments in exploration and drilling. When small independent gas producers argued otherwise, they were often ridiculed.

"I once had to tell the Exxon people in front of a congressional committee that I respectfully disagreed with every single thing they had presented," recalls Robert Hefner, 74, a veteran gas producer from Oklahoma.

But the natural gas folks now have numbers on their side due to new successes in getting gas out of shale rock. Geologists have always known that shale rock, often found in combination with coal and oil deposits, holds substantial amounts of natural gas. If a piece of shale rock is broken and lit with a match, it will actually burn for a few moments with a small flame.

The shale gas was previously considered unreachable, but advances in drilling techniques have changed that assessment. The result is a dramatic increase in estimated natural gas reserves. The Potential Gas Committee, loosely affiliated with the Colorado School of Mines, reported in June that natural gas reserves in the United States are actually 35 percent higher than believed just two years ago, and some geologists say even that estimate is too conservative.

Drowning In Natural Gas

"I used to say the nation is awash in natural gas," Hefner says. "Now I say we're drowning in it."

One area getting new attention is the Marcellus basin, a 400-million-year-old shale formation stretching from New York to West Virginia. That basin alone is believed to hold as much as 500 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, the equivalent of about 80 billion barrels of oil. (There are also large shale gas basins in Texas, Wyoming, Arkansas and Michigan.) It is not clear how much of the shale gas is recoverable, but the new production techniques have boosted all previous estimates.

Shale formations are deep underground — 6,000 feet or more — and the rock is relatively impermeable. Deep drilling is expensive, and in the past the amount of gas that could be reached was not considered sufficient to justify the cost.

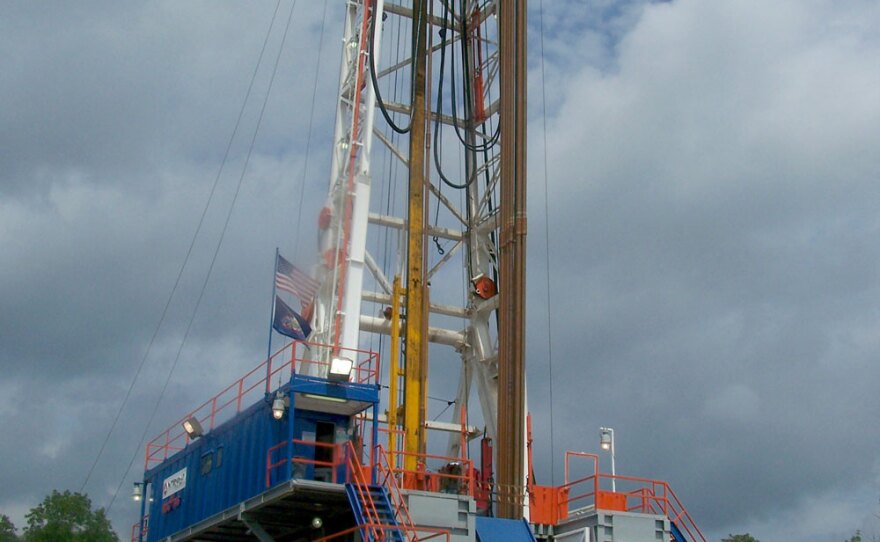

Horizontal Drilling

In recent years, however, gas producers expanded the use of "horizontal" drilling. After boring more than a mile below the Earth's surface to reach the shale layer, a drill operator will slowly "steer" the drill bit to one side, until it is heading sideways across the shale layer, thus achieving access to more of the shale than a traditional vertical well could provide.

Even so, the tightness of the shale rock would mean that relatively little of the trapped gas would seep into the pipeline. Gas producers therefore fracture the rock by forcing a water and sand mixture into the formation at very high pressure. This "water fracturing" technique opens millions of tiny cracks in the rock, enabling more of the gas to seep out.

Horizontal drilling and water fracturing are not new techniques in the oil and gas business, but only in recent years have producers used the procedures in combination to produce shale gas, and the results have been dramatic.

"It's the biggest thing I've ever even heard of," says Ray Walker, vice president of Range Resources, a gas exploration and production company. "It's huge. The ability to produce these shale reservoirs is going to revolutionize this industry all over the world."

Walker moved to Pennsylvania from Texas two years ago to direct his Fort Worth-based company's exploration of the Marcellus basin. Since then, Range Resources has dug more than 40 horizontal wells in Pennsylvania, and several dozen more are in preparation. In Texas, Wyoming and other areas, it's the same story.

Spreading The Word

"[Shale gas] is the most important energy development since the discovery of oil," says Fred Julander, founder and chief executive of his own Denver-based gas company, Julander Energy.

But the word has not yet spread as far as gas advocates would like. Ian Cronshaw, the top gas analyst at the Paris-based International Energy Agency, highlighted the jump in estimated gas in his most recent energy outlook report, but noted that the news had gotten little notice. "If that had happened in the oil industry, it would be a headline item," Cronshaw said at a recent meeting in Washington. "But because it happened in gas, nobody seems to be paying any attention."

As an energy source, natural gas is cheaper than oil, and when burned it produces only about half the carbon dioxide that comes from burning coal. As long as natural gas reserves in the United States were believed to be nearing depletion, the fuel did not get much attention, but with the upward revision of estimated reserves, that has changed.

"Natural gas is the fuel that can change everything for our nation," says Robert Hefner, who lays out his case in a new book, The Grand Energy Transition. Hefner argues that a big boost in the use of natural gas would dramatically lower greenhouse gas emissions and reduce the U.S. dependence on foreign oil. Much of the nation's electrical power now generated by burning coal could instead come from natural gas, and a switch to natural gas-powered automobiles would produce dramatic results.

"If we were to convert half of our existing vehicle fleet [to natural gas], we would eliminate a little over half our oil imports," Hefner contends. He and other natural gas advocates have been supported in recent months by environmental organizations.

"There's a huge capacity of natural gas that is lying idle," says Timothy Wirth, a former Democratic senator from Colorado who now heads the United Nations Foundation. "That makes absolutely no sense at all when what we're trying to do is clean up the atmosphere."

A 'Transition' Fuel

Natural gas is still a fossil fuel, and when burned it does produce greenhouse gases. Environmentalists working for the use of renewable energy sources nonetheless see natural gas as a transition fuel. One idea is to build mini-power generating stations, each connected to the natural gas pipeline infrastructure. A station attached to a hospital or a shopping mall could produce heat as well as electrical power, cutting energy costs dramatically.

"You can combine that with improvements in end-use efficiency and the development of renewable energy sources, and really see these as a partnership," says Christopher Flavin, president of Worldwatch Institute, an environmental research organization.

"Even the International Energy Agency is saying the path for oil is downward, and suddenly we've got this very different picture for natural gas," says Flavin. "I think it's unfortunately not fully percolated into the understanding of what's possible among policymakers. But I think as that takes hold in the next few years, it's really going to change the game."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))