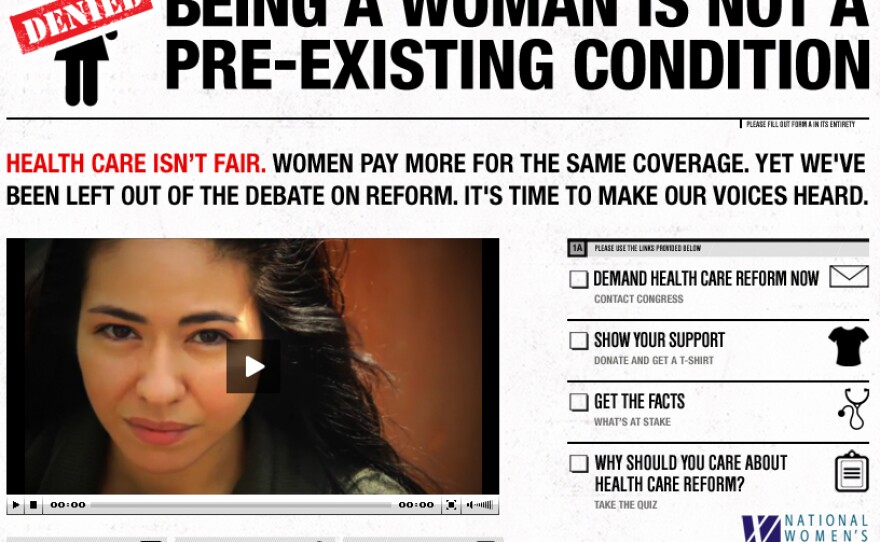

A photo of older white men in suits flashes on screen while a voice-over intones that "health care isn't fair: Men make the rules."

What follows are videos of a half-dozen women who, one after another, proclaim that they are "not a pre-existing condition."

A recent study by the National Women's Law Center found that 25-year-old women have been charged up to 84 percent more than their male contemporaries for individual health plans — plans that specifically exclude maternity coverage.

The online ad, part of a campaign launched this week by the National Women's Law Center, is more evidence of a stepped-up effort by women's health advocates and female Democratic senators to frame the health care overhaul debate, in part, as a battle of the sexes.

And Republicans like Sen. Jon Kyl of Arizona, who during a recent hearing asked why he should pay for a plan that covered maternity care when he didn't need it, have helped fuel the fight over whether women — during child-bearing years and into their 50s — can legally be charged more than their male contemporaries for the same health insurance policy.

"The health care debate has raised a lot of important women's issues and shined a spotlight on inequalities that still exist," says Alina Salganicoff, vice president for women's health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

"Women have a lot at stake right now — and great opportunity," she says.

Gender Disparities With Big Dollar Consequences

Overall, women in America are poorer than men, their health insurance is less secure, and, until they reach their mid-50s, they typically pay higher premiums, sometimes much higher, than their male counterparts.

A recent Women's Law Center study found that 25-year-old women have been charged up to 84 percent more than their male contemporaries for individual health plans that specifically exclude maternity coverage.

So as Democratic leaders from the Senate and the House continue to huddle with White House representatives to devise overhaul legislation, women's advocates have been targeting what they see as the main culprit in premium disparities: an insurance practice known as gender indexing or rating.

Already barred in 11 states, indexing is an insurance industry practice that factors in gender as one of many variables used to set insurance premiums.

Historically, it has disproportionately affected women who buy plans in the individual insurance market, and, to a lesser degree, those who participate in some group plans. Large employer-based plans are barred by federal law from imposing higher premiums based on gender.

In the open health insurance market, advocates argue, being a woman can be tantamount to a pre-existing medical condition.

Get Sterilized, Get Coverage?

During a recent Senate hearing on women and health care, Dr. Gerald Joseph of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists characterized the insurance coverage issues faced by women as "one of the most glaring reasons why we need health reform."

Not only are women charged higher premiums for individual coverage during their child-bearing years, but they also are typically required to purchase expensive riders for maternity coverage.

And there is a body of evidence that shows women have been denied coverage by insurance companies citing "pre-existing conditions" that range from having previously given birth by cesarean section to having been a victim of domestic abuse.

At the recent Senate hearing, led by Democratic Sen. Barbara Mikulski of Maryland, Peggy Robertson, a Colorado mother of two, testified that she was rejected by an insurance company that determined her previous cesarean constituted a pre-existing condition. Delivering a baby by surgical procedure increases a woman's chances of needing it again in future pregnancies.

The Golden Rule Insurance Co. told Robertson, 39, that if she had been sterilized, the coverage would have been hers. (Read part of a letter the insurer sent her.) Her story is now being featured in ads by the liberal advocacy group Americans United for Change.

Another woman told senators that premiums for her individual insurance policy and its $5,000 deductible for maternity care were so expensive that she had to drop the plan in order to have the money to pay for baby delivery bills that it did not cover.

"I don't know that women are disproportionately denied coverage for pre-existing conditions," says Judy Waxman, vice president of health and reproductive rights at the National Women's Law Center. Insurance companies, after all, aren't typically open about denial rates and targets.

"But there are many, many more ways that women can be turned down," Waxman says. "And the existence of gender rating has meant that women consistently pay more for their coverage, if they can even get it."

Simply Market Forces At Work?

Defenders of indexing say factoring in gender is no different from taking into account whether an applicant is a smoker or obese, or has pre-existing medical conditions.

For decades, the insurance industry has strenuously opposed so-called "gender neutral" rating proposals. It has argued that using gender indexing helps them more accurately assess the risk of the prospective policyholder, and that any law prohibiting the practice would be tantamount to government interference in the market.

But with more attention focused on the practice — and states like California barring the practice as a "discriminatory pricing scheme" — the industry has suggested that it could soften its opposition if the health care overhaul legislation requires that all individuals have health insurance to broaden and deepen the pool.

Both House and Senate overhaul proposals being considered would prohibit insurance companies from varying premium cost based on gender, as well as health status and occupation, and from denying coverage because of a pre-existing condition.

'Closer Than We've Ever Been'?

Karen Pollitz, a research professor at Georgetown University's Health Policy Institute, says insurers have proven a strong association between health care spending and demographic characteristics such as gender, age, occupation and even geographic location.

"Insurers are very sophisticated at detecting markers or risk, and, sure enough, women spend more on health care than men," Pollitz says. "They have all kinds of actuarial data to back up their rates.

"But that doesn't mean it's a good way to finance health insurance," she says. "It's not the same as car or fire insurance. Health insurance is life or death, and every single one of us, at some point in our lives, is going to use it."

Changes being considered in the health care overhaul would return health insurance companies to their role of paying claims, she says, and not so much selecting and sorting risk.

Women's health advocates say the prospects for a federal ban on gender indexing look promising, as does a proposed expansion of Medicaid, which would also affect more women than men.

Under proposals currently being considered, Medicaid would be expanded to Americans who earn the equivalent of 133 percent of the federal poverty level.

Three-quarters of those currently covered by Medicaid are women, Salganicoff says. And the earnings of half of America's uninsured fall below the 133 percent threshold, though some are legal and illegal immigrants who would not qualify for federal coverage.

The question of what benefits will be included in that expansion, and in a proposed public option or some variation, remains open. All are predicting a partisan debate around abortion and family planning issues.

But with the Senate and House nearing debate on their respective bills, Waxman — who worked on the failed Clinton White House health care overhaul effort in the early 1990s — says she's optimistic.

"We're closer now than we've ever been," she says.

As for Kyl, he's served as a rallying point, as has Sen. Debbie Stabenow. The Democrat from Michigan offered this quick response to the GOP senator's assertion that he doesn't need maternity benefits.

"I think," Stabenow said tartly, "your mom probably did."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))