Action on health care legislation now shifts to the Senate, where the process is expected to be slow and frustrating. In other words, business as usual in that chamber.

But experts on congressional process predict that the Senate will ultimately clear the health reconciliation bill that the House passed Sunday: Senate Republicans have the tools to slow the bill's progress, but not block it.

The Senate will take up the bill as early as Tuesday, at which point Republicans will try any and all strategies to delay and, if possible, derail this legislation. For anyone who follows the Senate on a regular basis, the process is going to feel familiar.

"In the Senate, all legislation is a mess. It's just that most people don't pay attention to it," says Donald Ritchie, the Senate's in-house historian. "This is a much larger case with more at stake on both sides, so everybody is going to use every tactic possible."

What Reconciliation Is About

The progress of health legislation looks particularly messy because it's turning out to be a multistep process. Shortly after passing the Senate's version of the health bill — clearing it for President Obama's signature — the House also passed a reconciliation bill that was, in essence, a package of amendments to the main bill.

The reconciliation process is used when Congress needs to make policy changes that affect spending or taxation in order to meet budgetary goals. Only items that directly affect either revenues or spending can be part of a reconciliation package. That's why there was no attempt to rewrite language in the main health bill having to do with the availability of insurance for illegal immigrants, for example.

The reconciliation bill does have several major tweaks on the earlier Senate bill, such as changing the penalties both for individuals who don't purchase health insurance and for companies that don't provide coverage to employees. It would delay the implementation of the so-called Cadillac tax on generous health care plans an additional five years, until 2018. And it seeks to answer complaints from states about Medicaid costs by increasing the federal share of coverage for those who enroll under the new law.

As everyone following the health debate knows by now, there's a big advantage for Senate Democrats in using reconciliation to move this legislation. It requires only 51 votes for passage, in contrast with the 60 votes required to bring filibusters to an end. Reconciliation measures are "privileged" and can't be filibustered.

A De Facto Filibuster

Senate debate on reconciliation will be limited to 20 hours. But that's sort of like reaching the two-minute warning in football. Real time is going to pass a lot more slowly because there will be plenty of timeouts called.

Votes don't count against the time limit, and there will be no limit on amendments. Republicans will be offering amendments by the dozens, if not hundreds. And reading the amendments out loud — something the GOP might insist on — doesn't count against the time limit, either.

A Test For The Democrats

From the Democratic perspective, the key thing is to stick together against any and all changes. If Republicans alter a single word, the bill would be sent back to the House for another vote — something House Democrats desperately want to avoid.

"Given the difficulty of crafting 216 votes for the first version, I'm sure leaders don't want to do that again," says Sarah A. Binder, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution.

That's why senators and aides from both sides of the aisle have been trooping in and out of the parliamentarian's office in recent days, double-checking which provisions will pass muster.

Senate Republicans know that if the parliamentarian upholds any of their challenges, Democrats would need 60 votes to overrule him — which they won't have.

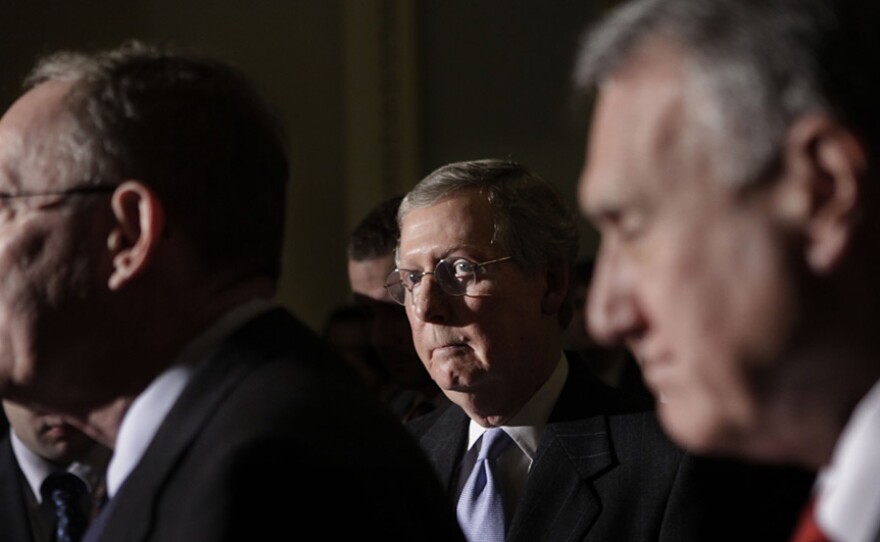

But with 59 votes, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) should be able to keep enough of his troops in line to prevail on votes against amendments. On Saturday, Reid presented a pledge from "more than 50" Democratic senators to his House counterparts that they will clear the House version for President Obama's signature.

So the test is really whether congressional Democrats have sufficiently scrubbed the measure to survive any procedural challenges.

Vote-Arama To Follow

The reconciliation process ends with what is lovingly referred to on Capitol Hill as a "vote-arama." The GOP will not be interested in reaching agreement on limiting the number of amendments that require a roll-call vote. Senate Republicans are not likely to offer their consent to anything that smooths this bill's process.

"The Senate does a huge percentage of its business by unanimous consent, and obviously there's not going to be unanimous consent for anything," says Ritchie, the Senate historian. "That's going to slow things down."

The End Of The Dance

All that delay will ultimately be for naught, predicts Bob Dove, who served as Senate parliamentarian for a dozen years under Republican majorities.

"You can expect a long, grueling process of amendments, but at some point that will stop," Dove says. "At some point, I think the Senate will pass the bill and send that bill to the president."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))