Baby cheetahs — fuzzy, grayish-gold cubs with dark spots on their legs and bellies and oversized claws — make a surprising noise: They chirp.

That is, unless they're trying to mark their independence.

"She was growling at me the other day, which is very cute," says cheetah biologist Adrienne Crosier at Smithsonian's Conservation Biology Institute, in Front Royal, Va. "She's 4 pounds of fury."

Earlier this month, the cubs were getting their daily weigh-in, plunked into a kind of measuring cup on a digital scale. They were a little over a month old.

"2.15 kilograms: She must have had a good lunch," says Crosier about the female cub.

These cubs were born 10 days apart. And here's what's unusual: Even though they're not siblings, these baby cheetahs are being raised by the same mother. It's called cross-fostering.

It "actually hasn't been done very often in North America. This is only the sixth time," Crosier says. She explains that if a cheetah gives birth to a single cub, she won't produce enough milk, and the cub will die. So when the first cub was born, a male singleton, they took him away from his mother and started bottle-feeding him.

"Really, there was not much of a choice in our minds that that was the best thing for the cub, because we absolutely wanted him to be able to survive," she says.

'She Took Right To The New Cub'

What was lucky was that another adult cheetah, 9-year-old Zazi, gave birth to her own cub, a female, soon after. So the Smithsonian staff decided to take a chance. They'd see if Zazi could be a foster mom, raising both cubs together. It was a gamble. The mom could have rejected the cub, maybe even killed it, says lead cheetah keeper Lacey Braun.

So the staff tried a few tricks.

"The night before, we did put the cub with her," Braun says. "We put the cub in shavings with her smells, so we did already introduce her smells onto the new cub. So we might have tricked her a little bit. And we rubbed the cubs together as well — just to get the other cub's smells on the new cub, so it's kinda like already her cub."

And it worked.

"[Zazi] was amazing," Braun says. "She took right to the new cub and just groomed it right away and accepted it willingly."

"She seemed to be just fine with having a second cub in there, and was nursing them both within about an hour," Crosier says.

The Smithsonian staff say it's better to cross-foster than to bottle-feed because cubs are easier to breed in the future if they were mothered than if they were hand-raised.

"A hand-raised cub just doesn't know how to communicate with the other cheetahs, basically, and is harder to breed," Braun says.

"I think a lot of hand-raised cheetah cubs — when they become adults — they're still very bonded to humans," Crosier says. "And the socialization that they have is stronger toward humans than to cheetahs, and they often don't show sexual interest in cheetahs of the opposite sex."

And breeding is the first priority. The wild cheetah population is designated as vulnerable to extinction. Over the past 100 years, the numbers have declined by almost 90 percent from about 100,000 to 12,000 — mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. So these cheetahs in Virginia are a hedge against extinction. The more research scientists can do on cheetahs in captivity — and the more genetic diversity they can build — the better equipped they are to save the wild species.

A Taste Of Independence

But for now, for these two young cubs, all that is far in the future. For now, it's all about small steps.

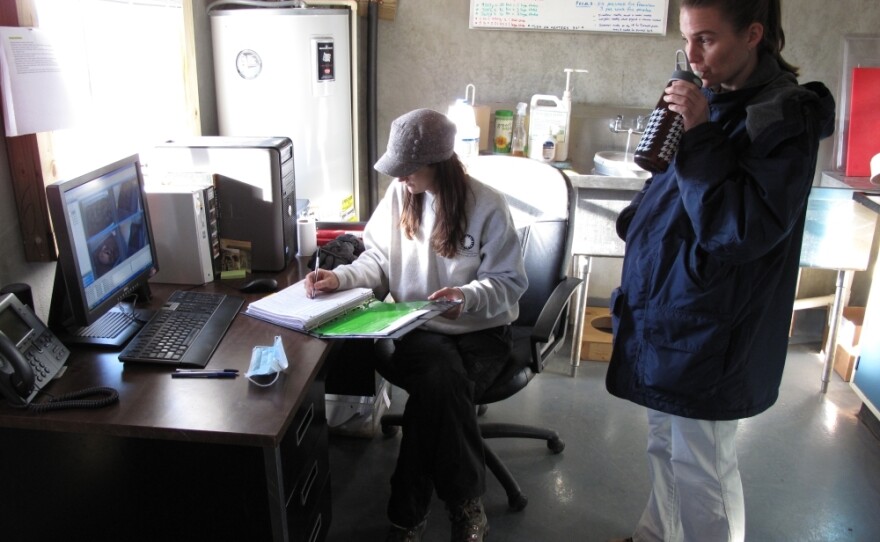

The cheetah cubs are living in a small shed with mom, who was put outside for our visit. Crosier and Braun only spend a few minutes a day inside the shed, but they watch over the cubs all the time through their cheetah cam. And on this day, as they watch on a monitor, the male cub thrills them. He toddles up to the edge of the nest box and steps out. It's his first taste of independence. Zazi, the mom, follows close behind.

"There she goes!" Crosier says. "She's trying to figure out where she wants him, as much as he's trying to figure out where he wants to go"

And where the baby cheetah wants to go is out.

"Oh, he's going again! Oh, he's such a stinker! Oh, give him up mom, let him go," Crosier says.

Since NPR visited, the female cheetah cub also made the big leap outside the nest box.

According to Crosier and Braun, they're both really active now — running around their shed and playing with each other a lot. Neither of the cubs have names as of yet.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))