Please hold your applause.

Hold it up to the light and examine it closely. At most large gatherings, ebullient clapping shows that there's approval and support. An event where there is round and raucous applause is considered a success.

But is that always true in politics?

Take the recent memorial service for the victims of the Tucson shootings. Applause for Obama's stirring words caused discomfort in some observers. They said it lent the affair an inappropriate pep-rally atmosphere.

And what about Tuesday's State of the Union address? If there is exuberant applause for the president's speech, will that really prove to be beneficial? If the speech is interrupted by repeated bursts of approbation, will that move the needle in a favorable way on the Obama barometer? Or does that simply show that Democrats are following the script?

Before watching tonight's spectacle, let's pause to consider — and take a brief historical look at — the politics of applause.

Clappers And Claquers

Clark McPhail studies applause. McPhail is a professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Illinois and author of The Myth of the Madding Crowd. He is fascinated by the phenomenon of clapping at State of the Union addresses and other high-profile events.

"There are some common features to applause across a wide range of religious, sport and political gatherings, not least of which is that you don't necessarily have to ask for applause to get it," McPhail says. "People clap to show approval of the utterances or actions that correspond to their preferences or biases."

For years, politicians have packed rallies and nominating conventions with partisan supporters, sycophants and claquers to applaud their speeches.

According to McPhail, neuroscientists have identified a "mirror neuron" phenomenon that explains "how the sights and sounds of another doing something that we already know how to do will trigger neurons in our brains that lead us to at least consider if not commence to do the same action ourselves."

Applause, he says, is not always spontaneous. And not always the result of pure free will. Sometimes applause is prompted by an emcee who encourages people by saying, "Let's have a big round of applause" or "Give it up." Other times, an ovation is sparked by "claquers." They're a subset of people in the gathering who are either shamelessly enthusiastic devotees of the person onstage or audience "plants" who have been drafted — sometimes even paid — to applaud a speaker or performer.

The practice of hiring claquers, McPhail says, is an age-old tradition among opera singers, actors and other theatrical performers. And, he adds, "for years, politicians have packed rallies and nominating conventions with partisan supporters, sycophants and claquers to applaud their speeches and support their nomination to high office."

In recent times, the president's partisan supporters —and opponents — have followed similar behavior when responding to the annual State of the Union address. "Advance copies of the speech are examined," McPhail explains, and "partisans pick those assertions with which they agree and arrange to respond with standing ovations. Opponents pick any assertion that even hints at a position they have advocated but which the president has virtually ignored and similarly arrange to respond with standing ovations."

William Safire noted the sea change in a 1987 column in The New York Times. He wrote that presidents once enjoyed bipartisan protection during the State of the Union speech. But "as opposition Congressmen began to take umbrage at being used as a passive backdrop, Speaker Tip O'Neill tried a little trick: passing the word to the Democrats to applaud wildly at some line that would give unintended meaning to what President Reagan said."

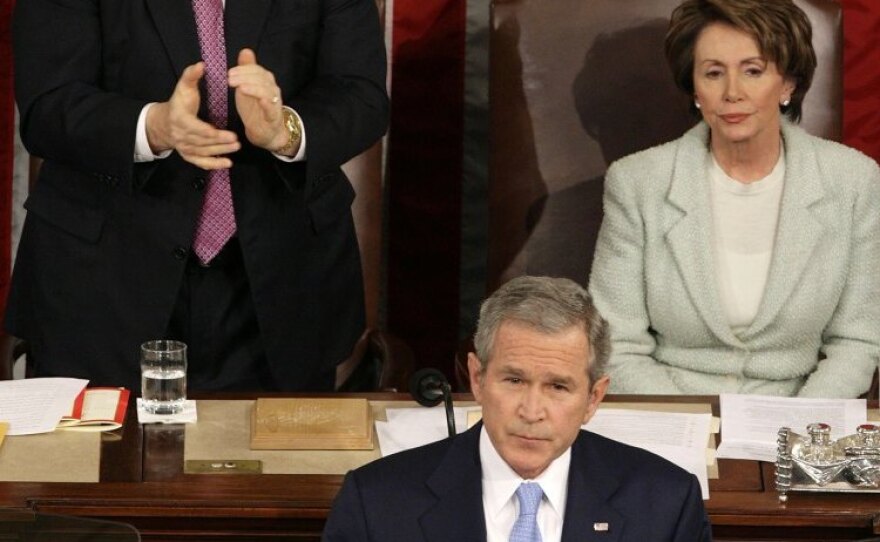

In the past quarter-century, audience response has become even more demonstrative. Last year the president's speech was interrupted by applause more than 80 times, according to several reports. Supporters jumped to their feet to applaud the mildest promise by Obama — resulting in a standing O for a smiling O. The president's detractors, meanwhile, looked glum and sat glued to their chairs.

Speaker Tip O'Neill tried a little trick: passing the word to the Democrats to applaud wildly at some line that would give unintended meaning to what President Reagan said.

Shocked By Applause

Sometimes the president knows when to pause and let enthusiasm erupt. And then there are times that the president is surprised, says Craig Smith, director of the Center for First Amendment Studies at California State University, Long Beach and a former speechwriter for Presidents Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush.

"The first time I wrote a speech for Ford," Smith says, "he was interrupted by applause and shocked by it. He lost his place, recovered and was interrupted many more times."

Among presidential wordsmiths, Smith says, "we don't know for sure when the applause is coming. On the other hand someone like Reagan always knew."

Smith recalls one instance in America's not-too-distant political past in which enthusiastic support for speeches did not translate into enthusiastic support at the polls. When John Connally of Texas ran for the Republican presidential nomination in 1980, Smith says, listeners were visibly more gung-ho for his campaign orations than those of Bush or of the ultimate nominee, Ronald Reagan.

But "after getting more applause lines than anyone else" in the race, Smith says, "Connally only got one delegate."

More than 30 years later, in this age of false promises, when good people get punked and Facebook friends aren't necessarily friendly, applause may mean less than ever. And given the new civility and the strange arrangement of bipartisan seating at Tuesday's State of the Union address, applause could be literally — and figuratively — all over the place. Denoting unity or signifying nothing.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))