In the 1920s, the sound of music in the black church underwent a revolution. Standing at 40th and State Street in Chicago, Roberts Temple Church of God in Christ was a witness to what occurred.

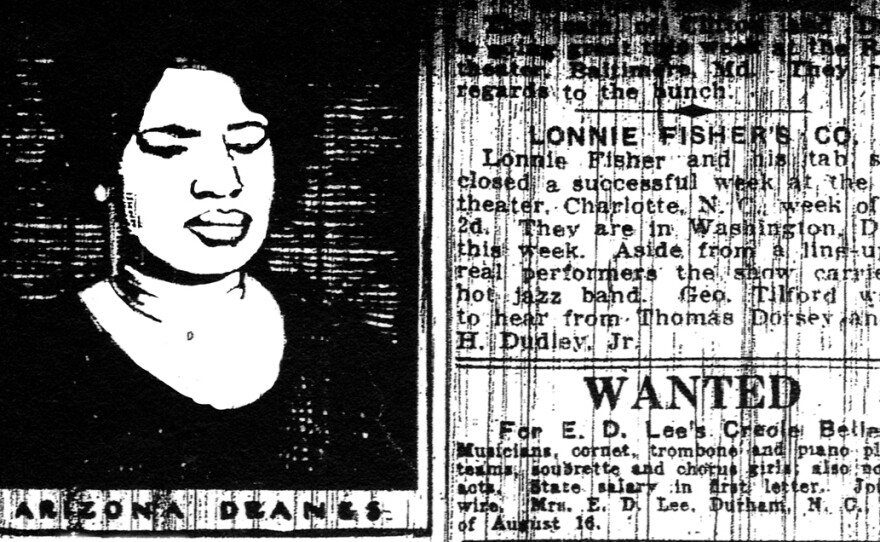

The high-energy gospel beat of the music that can still be heard in this Pentecostal church is the creation, music critics say, of Arizona Dranes, a blind piano player, a woman who introduced secular styles like barrelhouse and ragtime to the church's music.

The Chicago studio where Dranes recorded her music in 1926 no longer exists, but when she played her music at Roberts Temple, she influenced people like 11-year-old Sister Rosetta Tharpe, who sat in the congregation and would go on to become a gospel superstar.

"I mean, it was probably like hearing Jimi Hendrix for the first time," says music writer Michael Corcoran. "There was nothing like it before."

Corcoran has uncovered as much of Dranes' lost history as anyone ever has for the forthcoming CD package, He Is My Story: The Sanctified Soul of Arizona Dranes.

"She really was the first person to take secular styles and put words of praise on top of them to make gospel music," he tells NPR's Cheryl Corley. "It was extremely influential because people like Thomas Dorsey — who is correctly considered the father of gospel music — he figured, 'Well, I can take blues and put that to gospel music and come up with something new.' But he has acknowledged her as one of his influences."

Spirit Matched By Technique

Corcoran says it wouldn't be quite accurate to call Dranes the mother of gospel — her contribution was more specific than that. Dranes, he says, is responsible for giving gospel its rhythmic identity.

"She was Pentecostal," he says. "She was from the Church of God in Christ. I think they call them 'holy rollers' — they believe in speaking in tongues and really letting it go. Her music totally fit the church: The preachers would preach about spirit possession and then say, 'Here's Arizona Dranes.' And she would show them what they were talking about."

Dranes' life isn't well documented. It is known that she grew up in Texas, that she was a student at The Institute for Deaf, Dumb and Blind Colored Youth in Austin, and that she was classically trained. Corcoran says that with a little research, he discovered that Dranes was playing the works of Mozart and Beethoven by her early adolescence.

"It's really important to know that," Corcoran says. "When I first heard the music of Arizona Dranes, it was so spooky — it sounded like 1930s cartoon music, but the lyrics were about lamb's blood and the Crucifixion. Knowing that she was classically trained made a lot of sense, because she had such command of the piano. You match the spirit with her technique, and that is Arizona Dranes."

A Lasting Legacy, A Forgotten Life

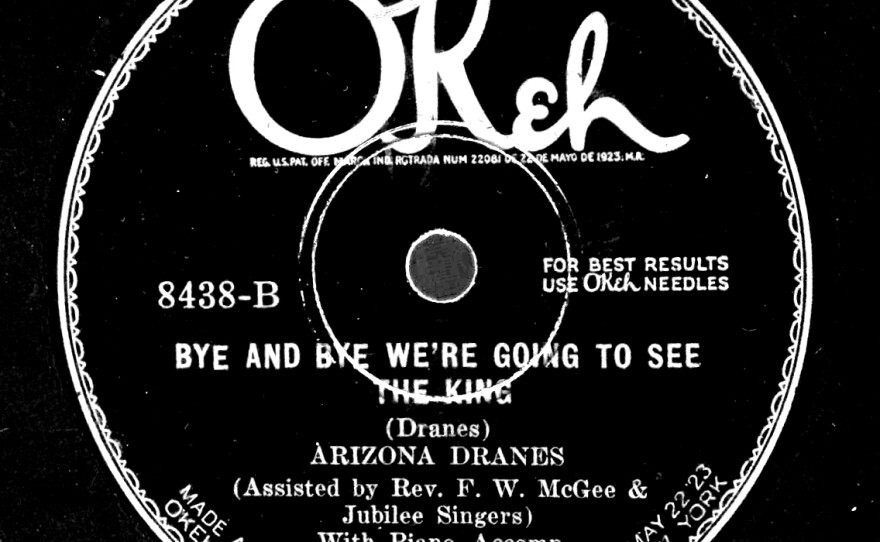

Dranes made her Chicago recordings in the late 1920s, after coming to the attention of an Okeh Records A&R representative who brought her to town to make a handful of test recordings. Corcoran says that by 1930s, however, the Great Depression had dried up demand for the style of raw, energetic performance Dranes specialized in, ending her recording career. She died in 1963; Corcoran says her passing went essentially unnoted.

"There was nothing at all," he says. "I can see where the general public wouldn't know much about her, because she didn't sell many records and she only played in church for the most part. But it really puzzled me that the Church of God in Christ didn't acknowledge her. ... I think that she was never really part of the church organization, and therefore was sort of forgotten through the years."

Though her name was mostly lost to history, Corcoran says, the lasting impact of her music is undeniable.

"You look at Little Richard and Ray Charles and Fats Domino and people like that — they sit down at the piano and they just lose themselves, but they're in complete control of their instrument," he says. "That all started with Arizona Dranes: There was no one before her who did that on record.

"I mean, Jerry Lee Lewis was Pentecostal, too," Corcoran adds. "If he didn't hear Arizona Dranes' records, he heard people that heard her records. I really think she's such an important figure, and completely obscure, for really no good reason."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))