Last September, dozens of public speakers gathered at the Imperial County Board of Supervisors meeting in El Centro. They were there to comment on the county’s proposed lithium spending plan — part of a major discussion taking place across the county about future tax revenue from the burgeoning industry.

But some of the speakers also wanted to talk about something else.

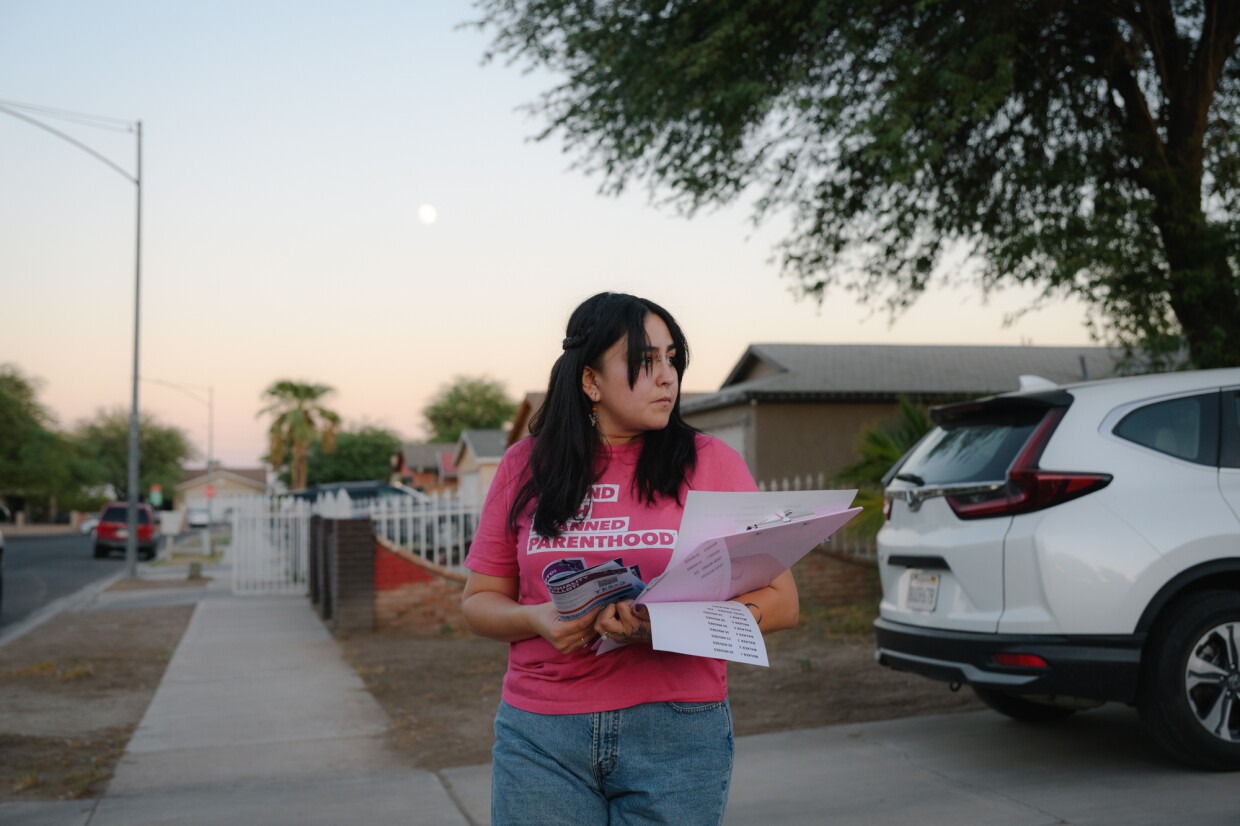

“There's no Spanish translation of the updated plan,” said Fernanda Vega, an organizer with the Imperial Valley Equity and Justice Coalition. “We cannot continue to push aside Spanish-speaking residents, especially when their health and livelihoods are at stake.”

Nearly 3 in 4 Imperial County residents speak mostly Spanish at home, and more than a quarter don’t speak English fluently, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. But the county government and many cities often don’t publish translated versions of agendas and other key documents.

Without consistent Spanish translation in local government, these residents are in essence locked out of the democratic process.

State auditors, local elected officials and civil rights groups have raised repeated concerns about what that means for the rural border region, which remains one of the poorest counties in California.

Many Imperial County residents describe a widespread lack of trust in local government, and people cast their ballots at one of the lowest rates in the state. Latino residents are far less likely to cast their ballots than white residents.

Now, a new California bill could force the county government and the region’s two largest cities to start offering Spanish translations of their meeting agendas, which are currently published only in English.

Among other changes, SB 707 would require that certain counties and cities with large communities who speak languages other than English translate their agendas and also provide translated instructions for tuning into meetings remotely.

In a speech on the California Senate floor earlier this month, the bill’s author, state Sen. María Elena Durazo (D-Los Angeles), said it would make it easier for non-English speakers to follow local government meetings and strengthen access to the democratic process.

Durazo put it simply: “This bill allows local governments to serve their communities better,” she said.

‘The majority language’

For most residents of Imperial County, Spanish is part of everyday life — 74% speak Spanish at home and over 25% are not fluent in English, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s latest American Communities Survey.

The percentages of Spanish-speaking residents are even higher in the county’s two largest cities, El Centro and Calexico.

In Calexico, an overwhelming majority of people, 93%, speak Spanish at home. More than half said they don’t speak English fluently. In El Centro, 76% of people speak Spanish at home, and a little less than a third reported not being fluent in English.

“Spanish is not the minority language,” Raul Ureña, the former mayor of Calexico, said of her city. “It is the majority language — the overwhelming majority.”

A result of all of this is many Imperial Valley residents have a harder time holding their elected officials accountable.

In 2022, the California state auditor’s office released a searing report on Calexico’s finances. The report found that previous city leaders had made decisions based on unreliable financial data and repeatedly overstretched their budget, creating an ongoing financial crisis and losing access to state grants.

In particular, auditors pointed out that Calexico only publishes its budget documents in English, creating a language barrier that effectively barred most residents from involving themselves in the process.

“Residents have asked that more information be presented in Spanish,” wrote Acting State Auditor Michael Tilden. “However, Calexico presents its key public budgetary documents in English only.”

One thing the city does offer is live, in-person Spanish interpretation during its meetings.

Other agencies in the county have also faced criticism over their lack of Spanish language materials.

In 2022, the ACLU accused the county Registrar of Voters of violating federal voting rights laws by failing to make key election materials available in Spanish. The Board of Supervisors has also faced repeated criticism over their lack of translation and interpretation.

Advocates for civic engagement have demanded more translation of documents and interpretation during meetings. Some environmental groups like IV Equity and Justice have taken to translating key planning documents and distributing them themselves.

Historian Benny Andrés says those barriers can lead many people, especially poor residents and people of color, to disengage from local government. Andrés is a professor of history at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte and author of the book “Power and Control in the Imperial Valley.”

“People don't think that much is going to change,” Andrés told KPBS last October. “And so a lot of people are apathetic because it’s like, ‘why bother?’”

Strengthening the Brown Act

As currently written, SB 707 would not require local governments to translate budget documents or provide live interpretation, but it would force the Board of Supervisors and the county’s larger cities to do more than they do now.

Along with Durazo, the bill is co-authored by state Sen. Jesse Arreguín (D-Oakland).

The lawmakers are seeking to strengthen parts of California’s Brown Act, which requires city councils, counties and school boards to hold open meetings that members of the public can attend.

The bill’s requirement for certain counties and cities to translate meeting agendas is significant. Agendas are important documents that describe the actions that elected officials consider and policies they may vote on during meetings.

On top of the requirements for translated agendas, the bill would task local governments with expanding online broadcasts of their meetings and improving access for people with disabilities.

SB 707 passed the Senate earlier this month and is now in the state Assembly.

Imperial County’s top elected officials have opposed the bill, citing the potential costs.

In a letter approved unanimously by the Board of Supervisors last week, County Chair John Hawk said it would be challenging for the county to pay for the required changes without funding from the state.

Historically, California automatically reimbursed county governments for the cost of complying with the Brown Act. But in 2014, voters approved Proposition 42, requiring counties to cover the costs themselves instead.

“Many of the proposed requirements are difficult to implement in regions like Imperial County, where broadband infrastructure is limited, and staffing capacity is already stretched thin,” Hawk wrote.

Other counties across the state, along with associations that represent county officials, have also raised worries about the bill, arguing that they are facing widespread funding challenges.

Although other parts of the bill might be more expensive, the cost of hiring a translator wouldn’t necessarily be extreme. In 2023, the city of Ventura estimated that translating one of their meeting agendas would be between $80 and $170.

Vega, the organizer who spoke up at the county lithium plan hearings, acknowledged that translation services may come at a price. But she feels the county should make it a priority and look into additional funding sources if they need to.

“The county needs to prioritize seeking out grants that can help,” she told KPBS in an interview last week. "That should really be part of their strategic plan.”

When she addressed the Board of Supervisors back in September, Vega was also speaking from personal experience. Her own parents, who live in Westmoreland, often feel like they cannot take part in public meetings because of the lack of translation.

“They've told us, ‘It's in English … I don't want to be in a space where I don't understand and I'm looking all confused,’” Vega said. “By literally just translating a meeting, you're already saying you're invited, you're important, we care about what you have to say.”

Even a meeting agenda, she said, is a start.