"Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle" airs on PBS stations April 29

MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: This is KPBS Midday Edition, I am Maureen Cavanagh. Forty-five years ago did journalists Ruben Salazar was thinking about being Latino in America that no one else would dare say out loud, and some people think that is why he lost his life. Salazar was a Los Angeles times reporter at the time when the Chicano political event was getting under way and he was killed in 1970 during a police action during an antiwar demonstration in LA. The documentary explores his work and his growing empathy with the Chicano movement and the mystery surrounding his half. The documentary Ruben Salazar, man in the middle areas next month and it's being filtered future today at the San Diego Latino film Festival. I would like to welcome Phillip Rodriguez, thank you for coming in. What is Ruben Salazar will remember for most? His germinal journalism or his politics? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: And personally neither, is ultimately his death, he died under mysterious circumstances under the hands of a Los Angeles police officer any and the case with and the circumstances were so unclear and the level of mistrust in the society was so great that very quickly he got turned into a martyr and unfortunately most of that was remembered about him was that he died under mysterious circumstances and was in perhaps killed intentionally by law enforcement officials. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: Tells about his background, where was he born and how did he get the LA Times? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: He was born in New Mexico and raised since infancy in El Paso and he came to the times in 1959 and was one of the very few nonwhites in that newsroom and grew to be a respected reporter and was sent a boat abroad to cover Vietnam and become station chief at Mexico City and was really in the middle of a lot of interesting action in a very fascinating period of history. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: From seeing your documentary it seems that Ruben Salazar became increasingly upset about the way that Latinos and Mexican immigrants were being marginalized and discriminated against, what kinds of things did he see that started his political information? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: Is very difficult from this to bring time and California history were Latinos in the majority of the population to imagine a time and they had absolutely no representation. Absolutely no voice in the media, Salazar comes from a place of relative entitlement to middle-class circumstances and was shocked by the degree to which Mexican Americans and Latinos are marginalized and often victimized by social forces, and he is outraged, fundamentally shocked, he was an assimilated Mexican-American married to a non-Latino religion and County, and he did not have an imagination for some of the injustices that he witnessed so in the course of his life as a middle-aged man and a journalist he confronted these realities and he has to figure out how he is to feel about it and switch do with them. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: What is his relationship like with the LA police department? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: He was with police beat as a young reporter in El Paso, and some of his friends say that he did not have the greatest trust for cops, as many people at work beats like that maybe don't. However, what is interesting about Salazar is a up until that point in Los Angeles history, the law enforcement had free reign and they were unjust by the state. Los Angeles times was simply a lackey of power and it really was not serious power until maybe mid-to-late 50s, Salazar comes at a time which the Los Angeles times has changed its relationship to the town and challenging authority in the way that it had not done previously and so he begins to report on what is going on and what the cops were doing, and that raise the higher of law enforcement and indeed he was called into law enforcement by Ed Davis and demanded that he stops doing these reporting and the Cleese cheese for police reported that Mexicans cannot handle your kind of reporting and you need to stop. Salazar refused. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: That was his turning point? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: It is hard to know what happens in a man's head, but certainly that is where the stakes get raised and he insisted that he had a right and an obligation to report on social realities and he is asked by a authority to six. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: Salazar himself when he began to be interviewed on the Chicano rights movement he said some provocative things, we show him being interviewed in the documentary, what are some of things that he had to say that were perhaps not being set up a time? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: The whole question of assimilation was an era in which up until that point the Mexican-American was by and large attempting to move themselves into white mainstream and into whiteness itself and to perhaps mimic those values of Anglo European society and at this point early in the 60s and I into the late 60s the Chicano nationalist separatist movement emerges where these young people begin to believe or insist that Mexicans don't need to be white but rather that should be themselves whether that whatever that may have meant and they should celebrate their otherness, what is interesting about Salazar is he was an assimilated Mexican-American with a non-Latino life and a non-Latino wife, is interesting to see him Jones by this new egoist of impatient, Brust and brush and demanding baby boomers are taught as part of the story. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: Part of the story and some of these amusing at the time I know in one of the interviews in the doctrine Terry, he said that there can be basically no such thing as American extra American because it undermines both of those words, that it does not mean anything, it does not help anybody try to help figure out who they are. PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: It was fashionable at that point and he cut up into the fashion of this nonwhite ethnic nationalism and it may have been in retrospect a cul-de-sac, admitted may have been if folly, maybe he lived in another time where he took on these identities and the fact is he dead, and his life was determined and his death and some days some ways was determined by these choices. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: The circumstances of his death were a age are part of his iconic status and some say he was liberally killed by a law enforcement and others say that it was an accident, I read that he was killed by shrapnel from it. Let gas explosive set off by a Sheriff's deputy during an antiwar process protest, is that a story that the perfect support? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: He was in fact killed by a tear gas projectile which hit his head, while he was sitting at a bar taking refuge from a stormy and turbulent demonstration. The teargas projectile was indeed fired by law enforcement official, whether or not this was intentional has been subject of great conjecture for over forty years, in order to get the bottom of it I petitioned and stood with the help of Mexican-American legal Defense and education fund for the right to access these people these public records which had been worth withheld and they refused access to for those years and with the help of that data was able to track down witnesses and the fellow that fired the gun and many of the interesting characters as well as Peru's the voluminous data and images to sort the case out and that is what we did. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: To people walked watching the government to come around them away with more answers our questions? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: I come think they come away with answers it is on your point of view but it I believe that the film does provide a rather thorough reading of the events. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: The title of your documentary is interesting you called Ruben Salazar at the man in the middle, what do you mean to buy that? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: He was a second-generation American who in the full flowering of his adulthood comes up against the favored them in baby boomer generation one set of values which is patience and assimilation and stoicism coming up against the shrill and aggressive and demanding and ethnic nationalist sensibilities of a boomer, he's in that crossfire and he's also the Queen white and brown so far in that he is the only nonwhite Latino in the newsroom and has to accommodate both of his identities he's a border man born in El Paso, his identity is always between the spaces and it was his job to negotiate that for himself and also negotiate that for a generation of Mexican Americans and Anglos, non-Mexican-Americans and needed some help and understanding the differences tween these cultures and how they're going to negotiate some kind of peace. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: As we talk about this and these 12 million Mexican Americans living in limbo in the US with no way to get legal status but on the other hand Latino voters of the fastest-growing voting population in the nation, what you think Ruben Souders Salazar would've made of the present state of Latinos in America? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: I don't know what to say to that. There are many more Ruben Salazar's.He was a singular figure who had access as a reporter for the Los Angeles Times and he was also a news director for Spanish language television and fortunately for us there are more voices now so there is no pressure, there is no equivalent amount of pressure to translate every aspect of this complex and difficult negotiation and I don't know, I would certainly, I'm afraid that I can't talk to about that. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: Did he, even though he did controversial things, did he pave the way for Latino journalists today? PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: Again, it's hard to measure his contribution, we only know that he was in extraordinary place in it dramatic moment of history, he put safety on the line for the sake of his job and I don't know how many people have that kind of character or commitment to their profession now, in that way if find it to be a very singular and extraordinary and washable individual and I walked away from doing this extraordinary amount of admiration for the fellow and his conviction and his commitment to the Constitution and the Bill of Rights and the pursuit of truth and a great risk. MAUREEN CAVANAUGH: Every remind everyone that the documentary will be airing on KPBS television and people twenty-ninth in this featured snide at the San Diego Latino film Fest or the festival and for details on that you can go to our website. I've been speaking with filmmaker Philip Rodriguez, thank you so much for speaking with us. PHILIP RODRIGUEZ: Thank you so much Maureen.

In the 1960s, journalist Ruben Salazar was writing about being Latino in America — things that no one else would dare say out loud. And some people think that's why he lost his life.

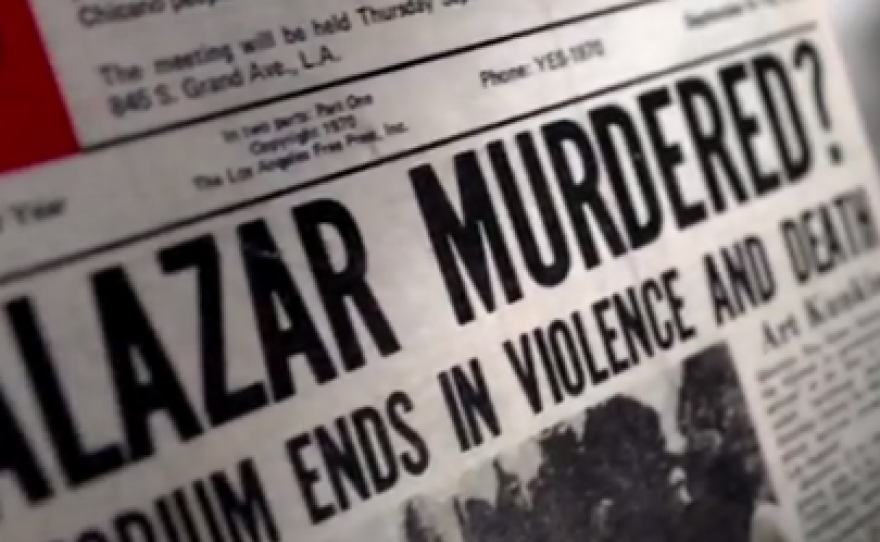

Salazar was a Los Angeles Times reporter at a time when the Chicano political movement was getting underway. He was killed in 1970 during a police action during an anti-war demonstration in L.A.

A new documentary explores Salazar's work, his growing empathy with the Chicano movement and the mysteries surrounding his death.

"Ruben Salazar: Man in the Middle" airs will be part of the San Diego Latino Film Festival this weekend.