If Vice President Joe Biden were to announce his presidential candidacy today, he would get into the race with 384 days until Election Day. And it may be too late for him be competitive.

Three hundred eight-four days is an absurdly long time.

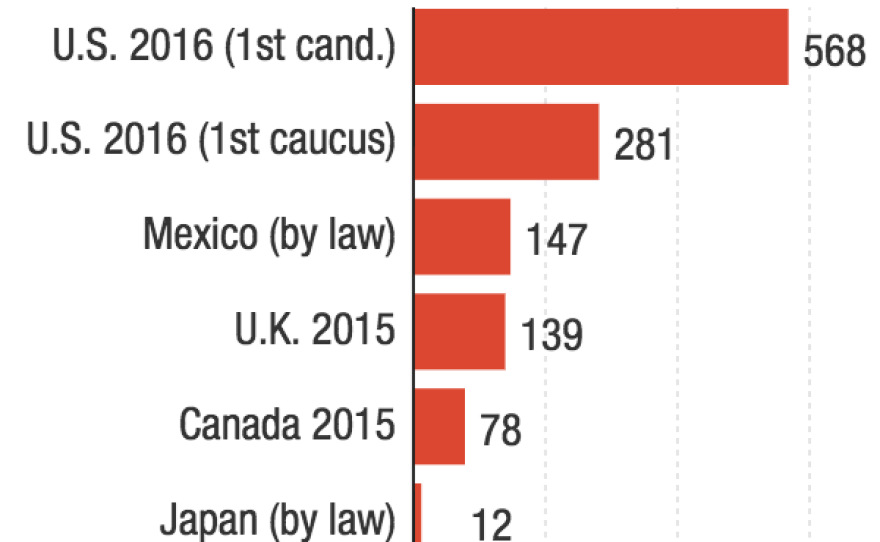

At least, it is when you compare American campaigns to those in other countries. The U.S. doesn't have an official campaign season, but the first candidate to jump into the presidential race, Ted Cruz, announced his candidacy on March 23 — 596 days before Election Day.

Meanwhile, Canada just wrapped up its latest campaign season. That one was longer than usual — at around 11 weeks. To the south, Mexican general election campaigns start 90 days before election day (and have to stop three days prior to the election), with an additional 60-day "pre-campaign" season, in which candidates vie for the nomination.

Different Laws And Different Systems

How do so many other countries keep their campaigns so short while the U.S. drags on so long? The simple answer is that many countries simply have laws dictating how long a campaign period is, while the U.S. doesn't.

In Mexico, a 2007 law limited the length of campaigns. In Argentina, advertisements can only begin 60 days before the election, and the official campaign itself can only start 25 days after that. In France, the presidential campaign is generally only two weeks long.

The system of government can also dictate the campaign season length. In many parliamentary systems, the campaign season is tied to the date when the prime minister dissolves parliament. In August, Prime Minister Stephen Harper dissolved Canada's parliament — 11 weeks before a scheduled election, making for the longest modern campaign season yet in that country, according to the CBC. (The minimum length of an election campaign in Canada is 36 days.)

And though the country has no legal limit on how long a campaign can be, it is constrained by that first date of dissolving parliament.

"That's only feasible with a short campaign period. We obviously couldn't dissolve the Congress 18 to 24 months in advance," says Michael Traugott, professor of political science at the University of Michigan.

Big Money In Politics

Laws may keep some countries' elections short, but other factors allow America's to go long — large amounts of money being chief among them. A candidate can't keep advertising for a year and a half, for example, without millions of dollars at his or her disposal. The U.S. system essentially requires candidates to raise millions of dollars to even mount a serious run.

"Voters in [Canada] would not have the tolerance or would not accept a system where that kind of money is spent on campaigns. There would be a huge uproar," said Don Abelson, professor of political science at the University of Western Ontario. "The elections tend to be very short. They don't tend to be terribly expensive."

Indeed, Canadians balked even at the country's recent 11-week campaign.

And in many countries, there's not room for a massive advertising arms race like the U.S. has, anyway. Brazil, the U.K. and Japan, among many others, simply don't allow candidates to purchase TV ads (but that doesn't mean zero ads — in some countries, like Japan, candidates each get equal, free, ad space).

Primary Creep

But the U.S. campaign hasn't always been an ultramarathon, and the presidential campaign didn't always drag on for a year and a half. Prior to the 1976 cycle, most presidential campaigns started within the election year, as Larry Sabato wrote in the Wall Street Journal (just imagine if all today's candidates were still three months from declaring).

But then Jimmy Carter decided to jump-start his Iowa campaign in 1975. That helped lead other candidates into the early race as well. Add in states' constant jostling to have the first primaries or caucuses, Sabato added, and it helped create the permanent campaign we all know today.

So What's The 'Right' System?

It's easy to think that the grass is greener across the border (or ocean). But it's not as if shorter systems are inherently better. Mexico, for example, is still dealing with the unintended consequences of its recent reforms, says one expert.

"The truth is that it's really impossible, or incredibly complicated, to create a system where the big problems can be removed without creating another set of problems," said Eric Magar, professor at the Mexico Autonomous Institute of Technology.

He points to the country's Green Party as an example. The government recently fined the party for running ads outside the campaign window.

True, the laws are being enforced, but the party's actions point to two problems in the nation's newly reformed system: One is that parties can simply run ads before it's legal, because they think it's worth the fine.

The other: They can use taxpayer money to pay those fines.

"Most of the money is public, so what ends up happening is they're using a bunch of taxpayer money to pay the fines," Magar says. "So it's a system that has lots of holes in its operations."

Other election systems can reinforce a party's power. The prime minister often chooses to disband parliament when his party is popular, Abelson explains, so his party can be assured of winning the next election. This can give the party in power an extra boost — not necessarily a bad outcome, depending on whom you support, but it's a system that plays a big part in determining who leads.

(As an example, Abelson points to a hypothetical Prime Minister George H.W. Bush. Had he called an election in 1991, when he was enormously popular, he could have far more easily held onto his spot than one year later, when his favorability ratings had plummeted.)

And some have made the case that Japan's uber-strict election laws go too far, keeping new ideas out of the public discourse.

Still, a shorter U.S. election season could have plenty of advantages — it wouldn't exhaust voters, and it might not require a candidate to amass tens of millions of dollars to even run, for example.

Not that change seems likely anytime soon. For U.S. voters sick of the perpetual electioneering, there's not much to do but gaze wistfully at other countries — or make that perennial "moving-to-Canada" threat.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.