As scientists struggle to understand the threat posed by Zika virus, there's another viral infection that's a known danger in pregnancy and that harms 100,000 babies a year, even though it has been preventable with a vaccine since 1969.

The disease is rubella, or German measles. Like Zika, the rubella virus often causes either a mild rash or no symptoms at all.

When women get rubella while pregnant, however, there can be devastating consequences for the fetus, including deafness, heart defects and even microcephaly — the brain abnormality that's raised such alarm about Zika.

Worldwide, about 300 infants a day are born with damage from rubella, according to Dr. Susan Reef, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's global immunization division, who notes that a dose of rubella vaccine can be purchased for about 50 cents.

"But in some countries, that's a big financial burden," Reef says, rattling off a list of nations that don't yet vaccinate, including India, Indonesia, Nigeria, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

About half of all children born worldwide have no access to rubella vaccine, she says. But more countries are starting to vaccinate, thanks to a recent push by the World Health Organization and increased funding from the GAVI Vaccine Alliance.

"It's a slow, gradual increase," Reef says.

The United States had a huge rubella outbreak in the 1960s, and in 1965 the disease made the cover of Life magazine, which warned that the virus would harm up to 20,000 babies in the U.S.

That's surely an underestimate, says Dr. Stanley Plotkin, now a professor emeritus of microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania, who had one of the few labs back then that could diagnose the disease.

"I calculated that 1 percent — one out of a hundred pregnancies in Philadelphia — were affected by rubella," says Plotkin. "I was constantly seeing women who wanted to know if they had been infected, and speaking with obstetricians who were either doing therapeutic abortions or delivering babies with congenital rubella."

As researchers try to figure out how much risk Zika virus poses to a fetus, Plotkin says it's deja vu for folks who lived through that extensive rubella outbreak.

"It enabled the virologists, among them myself, to describe in detail what the virus was doing and to show beyond any doubt that the virus was infecting the fetus and causing the abnormalities," says Plotkin.

The outbreak also forced major social changes, says Dr. Louis Cooper, a pediatrician and researcher who is now a professor emeritus of pediatrics with Columbia University. Back then, his small lab in New York was overwhelmed with women seeking tests and information.

"Before Roe v. Wade, because of the rubella outbreak, we were able to pass much more liberalized right-to-abortion [laws] in New York state," says Cooper, who adds that rubella also pushed the federal government to create new programs for special education.

Cooper became very close to families affected by rubella and feels deeply for women who now face Zika. "At the moment we have no way to stop the infection," he says, "and it doesn't look as if we have any way to reduce the risk to the developing babies." The size of that risk, he notes, remains to be quantified.

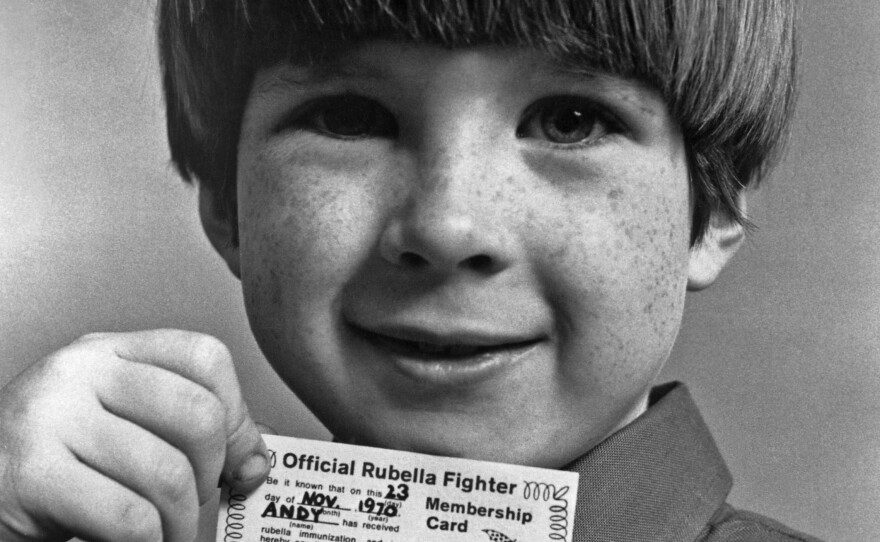

In some countries, like the United States, vaccination against the rubella virus was adopted quickly. And last year, public health officials said rubella had been eliminated from the Americas.

Still, seeing Zika in the headlines is a potent reminder of how scary rubella was for pregnant women. "It brings flashbacks of what rubella was like prior to the pre-vaccine era," says Reef.

Asked if Zika, like rubella, is likely to continue to harm infants even decades after a vaccine is developed, Reef says: "That's a great question, and I really don't know what's going to happen. Maybe that's a possibility."

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.