![Writer's Cabin, Montricher, Switzerland, 2015: "This suspended cabin had to balance comfort and compactness," Aravena says, adding that "the length of the cabin [allows] the writers to transit through different situations: cooking, eating and sharing."](https://cdn.kpbs.org/dims4/default/a8adf6d/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2953x1819+0+110/resize/880x542!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fkpbs-brightspot.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2016%2F01%2F12%2Falejandro-aravena-writers-cabin-01-0e1128beed6155d388b22a69ee1596917a6bcf78.jpg)

![Quinta Monroy Housing, Iquique, Chile, 2004: "The challenge of this project was to accommodate 100 families living in a 30-year-old slum," Aravena says. "We provided the families with the 'half a house' [top photo] that would be difficult for them to build for themselves and we gave them space to 'complete the house' as their means allowed [bottom photo]."](https://cdn.kpbs.org/dims4/default/a5fb898/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2998x1846+0+1212/resize/880x542!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fkpbs-brightspot.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com%2Fassets%2Fimg%2F2016%2F01%2F12%2Fhalfhouse_custom-384a6763be461701a9878680248bcd767da37af7.jpg)

The Pritzker Architecture Prize is often called the Nobel for architects, and this year's winner is 48-year-old Chilean designer Alejandro Aravena. His prestige projects include the headquarters of a pharmaceutical company in China and a dormitory at St. Edward's University in Austin, Texas.

But Aravena is known for socially conscious, sustainable design, often executed at staggering speed and on minuscule budgets.

He pays careful attention to residents of the places where he builds. Aravena gave a TED Talk last year about redesigning the Chilean port city of Constitución — in just three months — after a devastating 2010 earthquake. It includes video footage of fraught town hall meetings, with upset people loudly yelling about their concerns.

"Participatory design is not a hippy, romantic, 'let's all drink together about the future of the city' kind of thing," Aravena says in the talk, with a slight whiff of weariness.

Participatory design and the future of cities are two of Aravena's favorite topics. More than 2 billion new people will move into the world's cities in the next 15 years, Aravena said, and that means getting serious about sustainability.

"Sustainability is nothing but the rigorous use of common sense," he says from his office in Santiago. "If you are rigorous with common sense and a reasonable approach, almost every single architecture would be sustainable."

Aravena's common sense inspired his much-celebrated method of designing houses for 100 Chilean families living in slums. He had enough money to buy land or build houses. Aravena's solution? Buying the land and putting together frames with just a few livable rooms.

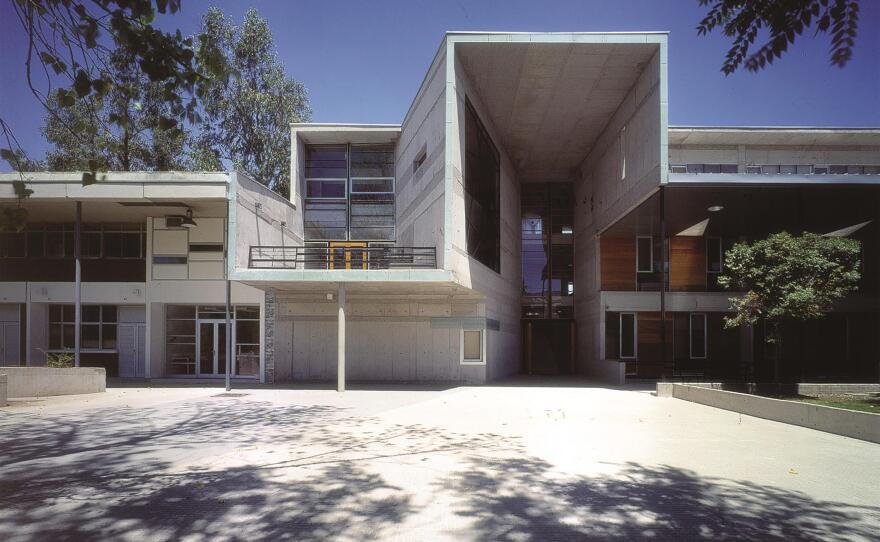

"He builds half a good house rather than building a whole, prepackaged crummy house," says Richard Sennett, approvingly. Sennett teaches urban studies and design at the London School of Economics and at New York University. He pointed out that Aravena's incremental houses gave people a chance to build out their frames according to their needs, and add extra rooms for lodgers or relatives. The two-story structures are basic and made of concrete.

"They're not beautiful," Sennett says. "It's a different kind of aesthetic than that. They're clean. There's no dramatic beauty in them. But when I look at the size of those rooms, I think — God, this is exactly right. It's not decorator beauty. It's deep beauty."

For his part, Aravena says Chile is short on beautiful, inspiring architecture. It didn't have an ancient empire like the Incas in Peru, he says, and the colonial Spanish did not leave sophisticated buildings behind. At least none that survived.

"We were always at war for more than 300 years," Aravena says. "And then, finally, nature, earthquakes have made their work, too. Almost every single old thing has disappeared."

Clearly, this is not an architect terribly sentimental about the art of building. Sennett says Aravena's selection as this year's Pritzker winner signals a generational shift.

"It's really a wonderful choice," Sennett says, adding that he hopes it will inspire other architects to address pressing new design challenges, such as climate change.

"Architects are mostly out of it, which is terrible. This is the big environmental story of our time, and we need to get young architects as leaders."

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.