It is the second week of classes at Cuyamaca College and already Leisha Ankers feels compelled to give her math teacher Terrie Nichols a teary-eyed thank you.

“Struggling with math is one of the biggest reasons I haven’t gotten a degree yet,” Ankers told her. “I was competent in every other area except math, and I failed so many times that I just gave up. If I can just finish math, I’m done here.”

Nichols hugged her. “You are exactly who I made this class for.”

Last year, Cuyamaca eliminated several layers of low-level math classes that students who test poorly must pass before taking math that will count toward their degrees. Extensive research has found many students get stuck in these remedial classes and never graduate, which is why Nichols calls them the “math pipeline of doom.” The problem is especially acute among students of color.

Earlier this month, the California State University Board of Trustees voted to eliminate its own “math pipeline of doom.” Now faculty at Cal State San Marcos and other CSU campuses are scrambling to overhaul of their curriculum in time for the next batch of freshmen.

RELATED: One Less Hurdle For California Transfer Students Beginning In 2018

Cuyamaca’s program offers a glimpse at what the overhauls could look like.

There, students who would have taken one to three semesters of remedial classes before stepping foot in a college-level statistics or precalculus class can opt for accelerated remediation or go straight into a transfer-level class. In both cases, any needed remediation is worked in.

Take Ankers’ class this week. The first half focused on tables.

“Why are we doing this exercise? What's my learning goal here?” Nichols asked her students during group work. “It turns out in statistics, what students have the most trouble with is reading the table correctly, so we're practicing reading a table before we get into some more interesting material.”

Within 15 minutes, the class moved seamlessly from the remediation to college-level work. Ankers took to the whiteboard with confidence to explain it to her peers.

The shift represents more than a change to the class schedule. To remediate students on the go, instructors had to change the way they taught. Nichols employs group work so students can help catch each other up and so she can observe and give individualized support as needed. Nichols said it is also important to couch the curriculum in real-world problems to help students connect.

“They can bring to bear their adult intelligence and their common sense,” Nichols said.

RELATED: San Diego, Imperial County Educators Gather To Improve Algebra Education

The approach opens new doors for non-traditional students far removed from high school math or who might never need college calculus in their careers.

“The last time I took a math class would have been in the late ‘70s, early ‘80s,” said Michael Smith, a 20-year veteran of the Navy. He passed Nichols' class last year.

“I was questioning myself, whether or not I could do it,” he said. “And if I would have had to have done every level, I wouldn't have done it.”

Now Smith is wrapping up his real estate degree so he can help other veterans find housing.

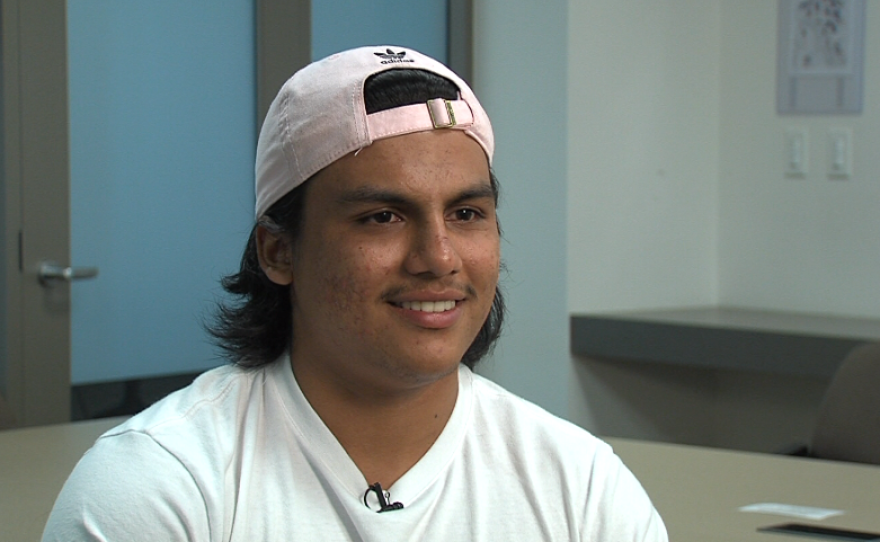

Caleb Rendon Guerrero came to Cuyamaca after spending his adolescence in and out of juvenile hall and bouncing from school to school.

“I was good with numbers, but with money more,” he said. “I grew up with five siblings and a single mom and I’m the second oldest, so I had to buy groceries when my mom was working and stuff like that. I had to be good with decimals and handling money, but fractions and all this other stuff they make us do, I never learned it.”

“I remember one time the teacher asked, ‘What do you want to be?’ And I said, ‘An architect.’ And he said, ‘Well, go play with Legos because that’s all you’re going to do. You’re bad at math,’” Guerrero said.

He came to Cuyamaca lacking confidence and said he probably would have dropped out if he had to take several remediation courses. Now he plans to finish his associate’s degree and start a nonprofit to help youth at risk of getting caught up in the criminal justice system like him.

Guerrero and Smith are two of several success stories. Nichols said before eliminating traditional remediation classes, just 10 percent of students who came to campus needing to catch up on high school math made it through a college-level course and were eligible for a degree.

“Whereas, now we have 67 percent passing a transfer level math class in one semester,” she said.

The change also helped narrow the achievement gap at Cuyamaca. The percentage of African-American students passing a transfer-level math class went from 6 percent before the change to 55 percent last year. Latino students passing went from 15 to 65 percent.

Cal State San Marcos Vice Provost Kamel Haddad said state universities in Tennessee, Georgia and Florida have also seen significant improvements since amending their remedial programs.

“We understand that the need is pressing to do better for the California student,” Haddad said. “So we will try our best to respond to the call.”

He doesn’t yet know what path his faculty will take. It could work remediation into its math classes like Cuyamaca or keep remediation classes but accelerate them and count them toward graduation. Currently, CSU remedial classes are non-credit bearing. They are beginning to make those decisions now.

“The faculty have to make all these changes in the Fall semester for the approval process to run through the Spring semester,” Haddad said. “And this is a challenging timeline for us to redesign several courses.”

The schools must also find a new way to determine which classes to places students in. The CSU is discontinuing the Entry Level Mathematics test it currently uses. It is unclear whether they will use a new test or the students’ high school grades.

Research from the Community College Research Center at Columbia University shows many students are “underplaced,” meaning their placement test scores land them in a remedial class when other predictors show they would pass a college-level course with a “B” or better. In one statewide community college system, between 14 and 28 percent of students were underplaced.

Grossmont College has already been working with local high schools to use class grades and state standardized test scores to place students. A statewide database will allow Grossmont and other colleges to place every student this way.

“We have helped hundreds, if not thousands, of students in this manner,” said Shirley Pereira, co-chair of Grossmont’s mathematics department.

Pereira said Grossmont won’t fully rid its class schedule of remedial courses so it can maintain options for its diverse student population. But it is piloting accelerated remediation to bring some students up to speed in one semester instead of two.

Meanwhile, K-12 educators are watching these changes closely and largely applauding what they are seeing.

Claudia Pruatt, a sixth-grade math teacher at Albert Einstein Academies, said the changes are forcing colleges to build classes that look more like hers — collaborative with individualized support, as opposed to a traditional lecture. Pruatt watched Cuyamaca’s Terrie Nichols present at a math symposium earlier this month.

“We were just like, ‘Yes! We know exactly what you’re talking about, and we get you, and we thank you,’” Pruatt said.

RELATED: Parents: It’s A Good Thing When Your Child’s Math Homework Scares You

Nichols, who plans to retire soon, will continue to meet with educators to share her curriculum — and her enthusiasm — as colleges work toward this new norm.

“I am born anew into the craft of teaching. And I am grateful to get to see 67 percent get through a transfer-level math class when before only 10 percent got through,” she told Pruatt and others at the symposium. “I get to end my career on that note. Like, f-yeah! It's all I want to talk about.”