When closures related to the coronavirus pandemic sent educators and artists into a flurry of online and distance learning practices and tools, many teachers and their students didn't have that luxury, especially those working with incarcerated individuals.

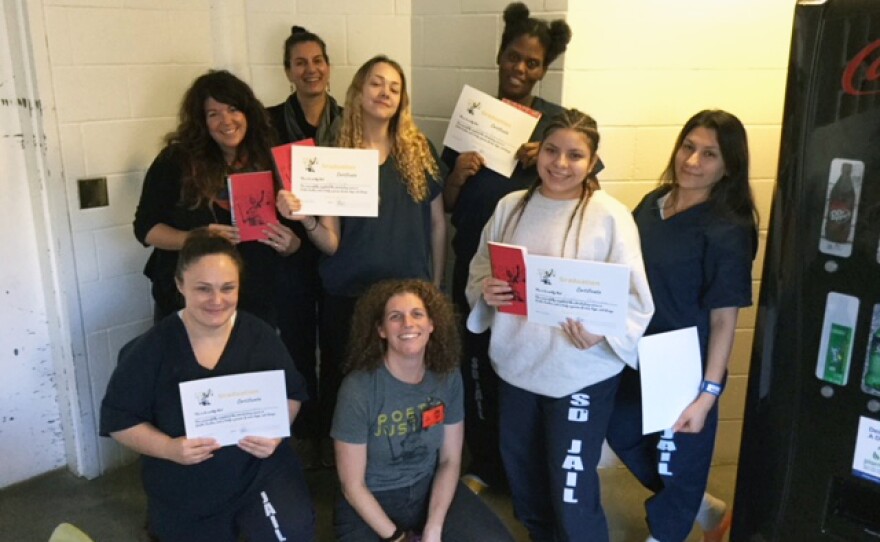

Poetic Justice, a nationwide nonprofit, brings poetry and restorative writing curriculum to incarcerated women, and has a chapter working with the Las Colinas Detention and Reentry Facility in Santee. The organization works closely with the reentry program at the facility to help incarcerated individuals make sense of their time in detention and prepare for reentry.

"Our mission at Poetic Justice is to really combat the root problems of trauma in people’s lives," said Katie Turner, Poetic Justice's California Program Director. Turner said that the sentences at Las Colinas are non-violent and generally drug-related. She said that often, the crimes trace back to problems with addiction or systemic problems associated with poverty or lack of education and resources. Reentry focuses on those elements, as well as individual trauma, and gives women a "leg up" for release, and the partnerships with arts programs like Poetic Justice play a crucial role.

Restorative writing uses writing instruction and practice to address the source of trauma — in many cases, a specific form of trauma known as adverse childhood experience (ACE). Poetic Justice's general, non-pandemic format is an eight-week course that builds from low-stakes community building exercises towards more intensive study, healing and trust building, and ultimately toward rejuvenating writing and building a sustainable feeling of hope.

Sometimes a Poetic Justice writing activity is simple, like writing a letter to their younger selves. Sometimes it's a deep study of a word like "grief." Towards the end of the program, they write about "the first fifteen." What will the women do in their first fifteen minutes after release? It's a specific, practical tool to reduce their chances of recidivism, but it's also a way of internalizing hope.

Poetic Justice volunteers write alongside the students, breaking down barriers and ensuring emotional trust and connection within the community. So what happens when that access is entirely cut off?

"That focus on emotional health is particularly challenging right now, for everyone in our community. But we are at home in our kitchens, we can eat our food, we can step outside onto our back porches. But for people who are incarcerated, when public officials say the word 'lockdown,' it's very ironic to me. What lockdown means to the incarcerated community and to individuals who are involved in the justice system, it's very different and it can be very emotionally difficult for them," Turner said, adding that practicing social distancing while incarcerated can be emotionally upsetting — on top of lifelong trauma and the impact of incarceration.

In traditional classrooms, teachers can adapt their learning environments with the use of digital classroom platforms, teleconferencing and even phone calls with their students, but the landscape within correctional facilities is starkly different. At Las Colinas, security restrictions rule out video conferencing, sending videos of recorded lessons or the use of digital connectivity platforms like Zoom.

"We really had to adapt. We had people going back and forth into classes every single week and then suddenly everyone stopped," said Turner. Instead, the nonprofit developed a new infrastructure to create assignments, receive and transcribe their students' work and find ways to communicate with them in general. They returned to a format that's more like an old-fashioned correspondence course than modern remote-learning.

The group sends new, individualized lessons to the reentry team at Las Colinas to print out and provide to the students. Turner, who has been teaching for 18 years, said that she specifically writes these lessons in first person, so that the students can recognize her voice and feel a connection. The students will then, in turn, write their assignments, which have shifted to focus more on finding joy and gratitude than being heavier, emotionally restorative prompts.

Poetic Justice volunteers then transcribe the works and begin to build the unit's anthology. They're also ramping up their own social media presence, and posting projects like "Lessons from the Inside," to help others understand what it's like to go through the classes, and posting samples of the student poetry each Friday.

"Poetry gives women who are incarcerated a voice, and by having a voice, they can begin to have hope, and by having hope, they can begin to change," Turner said. "And so at the end of every single class, we stand up, we hold hands and three times we repeat: I have a voice, I have hope, I have the power to change." These days, Turner includes this mantra at the end of her printed out lesson plans. She invites them to stand up "with" her and say it together. As together as they can be.