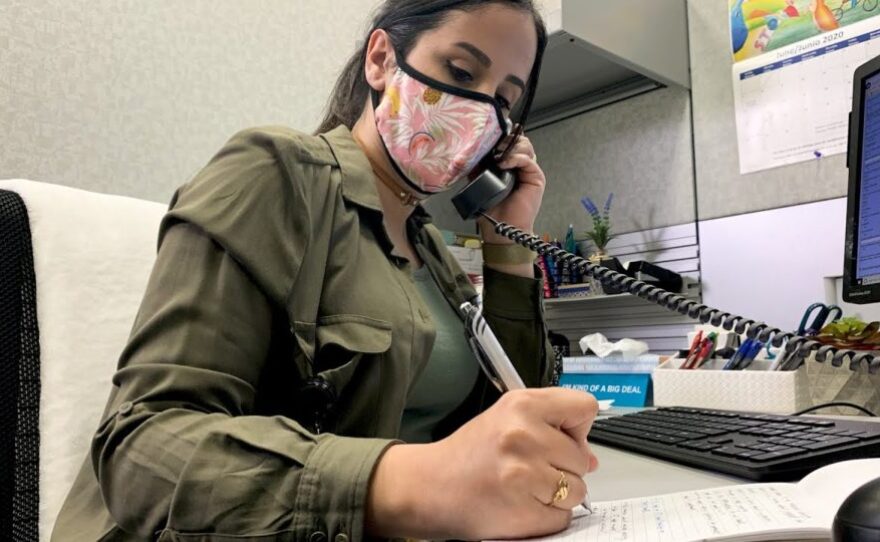

Every day, Asma Al Sabag goes to work and gives people bad news.

"I'll say, 'Hi, I'm calling because you were recently exposed to someone who tested positive for COVID-19,"' she said during a recent call.

Al Sabag is one of nearly 500 contact tracers working for San Diego County whose job it is to find and notify people who were likely in contact with someone who’s tested positive for the coronavirus. And while she's likely made hundreds of phone calls by now, all her hard work might not be paying off.

Since early March when San Diego County’s contact tracing program began tracking COVID-19 cases, tracers have only contacted about 9,000 county residents who were named as a close contact of someone with the virus, according to county spokeswoman Sarah Sweeney.

RELATED: San Diego Gearing Up To Deploy Hundreds Of Coronavirus Trackers

That's likely only a small fraction of those who've been exposed countywide. So far there have been about 17,000 known positive cases of COVID-19 in San Diego County, and each case on average has about 10 close contacts — people the infected person has been less than 6 feet away from for more than 15 minutes in the last two weeks.

Plus, the county does not know how many of the people contacted actually went into quarantine.

"At first, San Diego County and the state were saying it was a very high priority to have a robust contact tracing program," said Andrea LaCroix, an epidemiologist at UC San Diego. "It turned out to be much more difficult than they thought to standardize programs across the state and sew together different institutions. I wish we were farther along."

LaCroix and other epidemiologists say a regime consisting of widespread wearing of face coverings, social distancing, testing and contact tracing is the only safe way to slow the spread of the disease until a vaccine is available.

Cases in the county, however, have surged in recent weeks after the positive test rate trended downward for most of May. Officials say it’s safe to assume the numbers would be even higher without the contact tracing program, but it’s impossible to know how much higher.

U.S. Lags Other Countries

Contact tracing has proven effective in countries with authoritarian systems such as China and those with populations that are generally more compliant with government authority such as South Korea and Germany.

In the U.S., however, San Diego is just one of a number of places where programs are struggling. An NPR survey found that only seven states and Washington DC have enough contact tracers to contain outbreaks. California currently has 6,000 contact tracers statewide, about half of what it would need, according to the survey.

Meanwhile, New York City has hired 3,000 contact tracers, but still, only 42% of people who had coronavirus gave contact tracers information about their close contacts.

The number of contact tracers in San Diego County is approaching what experts say is needed. They typically make 10 to 15 calls a day. The county tracks the percentage of cases they are able to begin investigating within 24 hours.

If the percentage dips below 70%, that's a trigger indicating the contact tracing system is overwhelmed. Late last week, the trigger was hit, and on Monday the investigation rate fell to 57%.

This is even more concerning given that San Diego contact tracers are only required to call people on the first day to tell them about the exposure and at the end of the 14-day quarantine period. Only people with cases that are considered high risk are called more often. In Massachusetts, contact tracers call people every day during their quarantine period.

Al Sabag said 90% of the time, the person she's calling already knows the news she will give.

"They'll say, 'Yes, I know who it is,'" she said because the person with COVID-19 is a family member or close friend. Then, she helps that person find his or her exposure date — the last time they were within 6 feet of the sick person for more than 15 minutes. The 14-day quarantine begins on that date.

But other times, the person who gets a call from a contact tracer reacts with anger, Al Sabag said.

"They'll refuse to complete the interview until we tell them who they were exposed to," she said, which contact tracers won't do. "So they may hang up on us."

If that happens, contact tracers will call back two more times, and then mail the person a letter telling them how to stay safe. At the end of the 14 days, a contact tracer will call back again and "at least try to find out if the person had symptoms," Al Sabag said.

A PR Quandary

Jeff Johnson, the head of the county's contact tracing program, acknowledges the limitations.

"We tell them we really want them to quarantine themselves, and if they're threatening to go to work, we'll have to talk with them and advise them otherwise," Johnson said. "If we become aware someone has threatened to leave, we'd have to verify that first, and if they went to work, we'd call their employer, work with their HR, and keep giving friendly recommendations."

If a person does develop symptoms or tests positive for COVID-19, the county then has the authority to force that person into quarantine, Johnson said.

"There have been a couple situations where we had to issue a specific health order to a person at a specific location," he said. "But the vast majority of people have been very compliant and supportive."

Johnson declined to go into details about when someone has needed a health order to force them to stay home, but said there have been times when a law enforcement officer or San Diego County Sheriff's deputy has "physically issued it."

"It's very rare but in those very few situations, we'll have law enforcement get involved," he said.

The county doesn't want to look too heavy-handed in its enforcement, said LaCroix, the epidemiologist at UC San Diego.

"There's a big PR aspect to this," LaCroix said. "The quarantine notice from the county is a legal document, but they have no intention of chasing down people and putting them in jail. We're depending on each other and our mutual goodwill to stay home."

At first, contact tracers hired by the county were using personal cell phones or Google voice numbers, but now the county has rolled out phones for everyone. They allow a special caller ID to show up when a contact tracer calls — SD COUNTY COVID — so people know to answer the phone, Johnson said.

The county is also considering a text message system, but right now the plan is to stay with the current system for six to nine months, he said.

A few months ago, county health officials also said they would consider developing a contact tracing app that would use Bluetooth technology to track people via their phones. But Johnson said those plans are on hold for now.

RELATED: It’s Public Health Vs. Privacy As San Diego County Considers Contact Tracing App

"We have been engaging with several groups, it could be a simple app that just sends text messages as reminders, or it could be the proximity app that was well-publicized," he said. "We'd have to go through a process where any technology used by the county goes through an IT review and privacy and security review."

He said in the fall or winter, the county could look to other technology like apps to make contact tracing more efficient.

LaCroix with UC San Diego said that widely available testing also makes tracing easier.

If she got a call from a contact tracer, "the first thing I would do is get tested," she said.

A Cultural Divide

Another reality that could be limiting the program’s effectiveness is a lack of bilingual contact tracers.

Asma Al Sabag speaks Arabic in addition to English, but not many other contact tracers speak a second language. There is currently one other contact tracer on staff at the county who speaks Arabic, and 41 who speak Spanish — just under 10% of all the contact tracers. Three contact tracers speak Chinese, one speaks Vietnamese and eight speak Tagalog or Filipino.

Al Sabag said many of the calls she makes are to people who speak Spanish, so she uses software called Language Line that does translation for her. She said she doesn't think that cultural awareness comes into play when making contact tracing calls, but it's important to have sensitivity to different socioeconomic backgrounds. For example, someone may not have health benefits or won't get paid if they stay home from work.

But Johnson, the head of the program, said cultural sensitivity is important. The county is partnering with SDSU to train people from Arabic-speaking, Spanish-speaking and African American communities to do contact tracing and community health work. The first person from that program began working last week.

The county also has an online training system and assigns cultural diversity training to contact tracers, he said.

As for Al Sabag, she plans to continue going to work and helping people through the challenging phone calls they received.

"I'll keep doing this until contact tracing is no longer a thing until there's a vaccine," she said.