Noir reading list

August: "Build My Gallows High" (filmed as "Out of the Past") by Geoffrey Homes

September: "Pitfall" by Jay Dratler

October: "Gun Crazy: The Birth of Outlaw Cinema" by Eddie Muller

November: "The Big Heat" by William McGivern

December: "Badge of Evil" (filmed as "Touch of Evil") by Whit Masterson

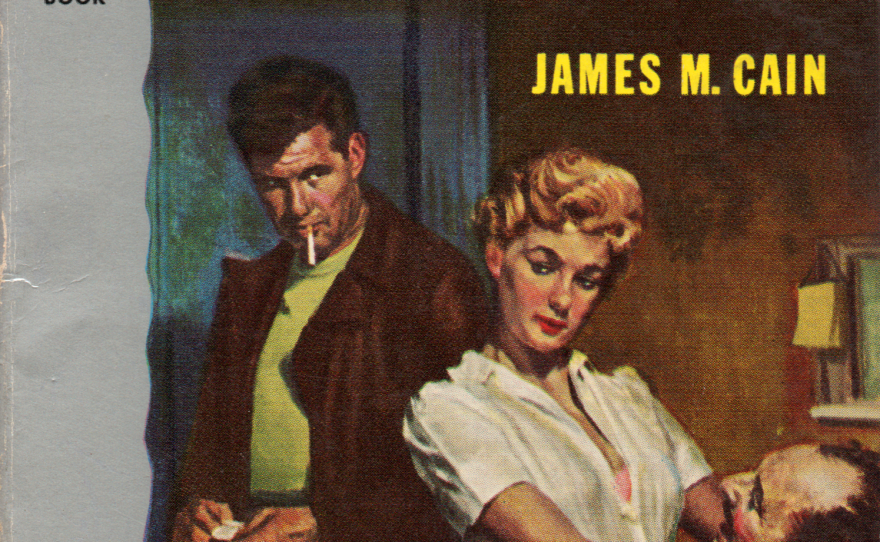

Guest blogger D.A. Kolodenko looks to James M. Cain’s “"The Postman Always Rings Twice" and Marty Holland's Can-inspired "Fallen Angel" for the August Noir Book of the Month Club to complement the Film Geeks SD Noir on the Boulevard film series at Digital Gym Cinema.

Cain and Cainism: 'The Postman Always Rings Twice' and 'Fallen Angel'

An unscrupulous narcissist narrates his downfall, identifying as its starting point a random encounter with a desirable woman whose husband is in the way. If it sounds like James M. Cain’s "Double Indemnity," our May novel in the KPBS Noir Book of the Month Club, it’s because Cain’s first published story, "The Postman Always Rings Twice" (1934) — the basis of the film screened at July’s Noir on the Boulevard — was also inspired by the real-life Ruth Snyder murder case, which Cain covered as a journalist in the 1920s.

Although he wrote 21 novels and novellas in a wide array of styles and genres, because of the international successes of Cain’s two stories with this love/murder triangle theme, and of the 1944 and '46 films based on them, any story in which lovers plot to get rid of a spouse will inevitably be described as Cainian. And it’s fair to say, because he’s in his wheelhouse in these stories: terse, lean, stark, suspenseful, imminently readable, with an unerring ear for plainspokenness, Cain strikes an artful balance between sympathy, disgust, and amusement in considering the dreadful follies of ordinary but damaged men and women and their karmic unravelling. It’s no wonder "Postman" is among Library Journal’s top 100 American novels.

As delighted as anyone that Cain wrote "Double Indemnity," I’ve never really understood why he did, considering how much it echoes "The Postman Always Rings Twice." He wasn’t obsessed with the Snyder case to the point of having written anything more about it after covering it, but to base two novels written within a few years of each other on that same case, with both told from the first-person perspective of the male anti-protagonist, seems excessive.

Cain versus Cain

Whether or not both stories were necessary, each is terrifically readable, and there are significant differences between them.

For one, the attraction of Frank and Cora is as raw as 1934 gets — the animalistic carnality still feels shocking in context. It’s not surprising that the book was tried for obscenity in a Boston court; it’s surprising that it was only tried in one city.

Walter and Phyllis in "Double Indemnity" seem less driven by lust for each other and more for the enrichment they foolishly expect as the outcome of their conspiracy. While Frank and Cora do see getting rid of Nick as a way to get ahead, the idea to cash in on murder emerges after their violent hookup — it’s a way for them to be together, not the force driving them to use each other.

"Double Indemnity" is about sex as a means an end; "Postman" is about sex as a force that makes anything possible. One of the reasons Billy Wilder’s "Double Indemnity" is a better film than Tay Garnett’s "Postman" may be that without their sadomasochistic impulses, Frank and Cora just aren’t as interesting as the venal and conniving Walter and Phyllis.

But there’s more to "Postman" than sex. Cora isn’t a psychotic angel of death like Phyllis; she’s a young brunette lowlife who’s sick to death of the struggle to prove she’s lily white — not easy when she’s often mistaken for Mexican (even at first by Frank) and married to a much older Greek immigrant.

Underlying Cora’s attraction to Frank, the clever hobo, is his whiteness.

Nick may be an American success story with a closet full of silk suits and his own gas station and cafe, but Cora’s resentment toward her husband drives her desire for Frank to replace him. She doesn’t want a different life; she wants the café filled with white customers. Nick proudly imagines he’s achieved the American dream; the racist poison in Cora’s brain and cravenness in Frank’s will turn it into a nightmare.

The replacement of Nick with a dull, white husband in the film version is a major omission. The film barely makes sense without him. It’s hard to blame Garnett, though. The Hays code and MGM’s reluctance to touch anything weighty meant that the most interesting things about Cain’s story would never have made it to the screen even if Garnett had tried. The screen presences of John Garfield and Lana Turner, however, are alone worth the price of admission.

In the Cain vein: sympathy for the devil in Marty Holland’s 'Fallen Angel'

If you came out to April’s Noir on the Boulevard screening of Otto Preminger’s entertaining film version of the novel "Fallen Angel" by Marty Holland (real name, Mary Hauenstein), you may recognize that the opening of "Fallen Angel" was influenced by the opening of "The Postman Always Rings Twice:" a sharp-talking drifter gets thrown off a vehicle in California and wanders into a roadside diner owned by an old guy, where he meets a sexy young waitress and decides to stick around and see if he can hustle her.

Yeah, it’s a rip off, but Cain liked the way Holland wrote. He reviewed the book favorably and wrote the blurb for the jacket on her second novel, "The Glass Heart," which he later adapted as a screenplay, which was never filmed.

Cain must have been flattered by her imitation of his style, which she did as well as any of his male imitators. Holland had already cut her teeth writing short stories for pulp crime magazines during World War II, adopting the nom de plume Marty, no doubt to convince publishers she was a he, as it can’t be overstated how much writing crime stories was a male-dominated domain in 1945.

Holland had always wanted to be a writer since she was a little girl in Beaverdam, Ohio, but there’s no evidence of her work prior to her family’s move to Hollywood, where she obtained work as a movie studio typist and began submitting mysteries to the pulps.

Holland was attractive and also tried acting on the stage but didn’t go far with it. Her family recalls that she lived in a small apartment in the Beverly Hills building that her mother owned. Their memory of Holland is that she spent most of her time in there working at her typewriter, and that she liked to snack on chocolate and owned a gun.

Holland was private, somewhat secretive and never married. Her ambition to be a great writer seemed to be her primary passion.

"Fallen Angel" was her first novel. It may be that her studio connections helped her get the unpublished manuscript read, but somehow Otto Preminger got a hold of it, liked it, and decided to film it. That’s why the novel and film were both released in 1945.

Most noir aficionados would argue that neither the novel nor the screen adaptation really qualifies as a true noir: the first third of the story is promising, with its doom-laden atmosphere and the drifter Eric Stanton’s plot to con an innocent townie for her wealth using a phony medium racket with the help of a traveling spiritualist played effectively in the film by John Carradine. Will Stanton get the money and run off with Stella the waitress and live happily ever after? Fat chance.

Performed by the immensely watchable and convincing Linda Darnell, Stella is knocked off before he can get a dime out of the spinster, and the plot evolves into a whodunnit. What keeps it somewhat noirish, in spite of the considerable drop off in excitement after Stella’s demise, is that the motive of every suspect is an unhealthy obsession with Stella that makes them all believable as the killer.

Holland has fun exposing the pathetic desperation of the men and takes it further than the film, which for some reason deletes an important clue pointing at Pop, the diner owner, which turns out to be a frame that makes sense at the final reveal. The film’s romantic coda is even cheesier in the novel — this isn’t one of those tacked on endings to satisfy the Hays code moral police; this is redemption. That’s not noir and it almost never convinces in these stories. But that hardly matters: once Linda Darnell is out of the picture, I’m only half in.

Overall, the movie works: the mystery holds interest, the photography by Joseph LaShelle is studio craft perfection, and it’s always easy to care about what happens to Dana Andrews (more so, though, in Preminger’s best Andrews vehicle, "Where The Sidewalk Ends"). The novel’s mitigating factor is Holland’s streamlined prose and her interest in the power of her female characters to shape men’s lives.

More hot summer night reads

As I write this, we just screened "Out of The Past" and I’m in the middle of my third read of its excellent origin novel, Daniel Mainwaring’s (a.k.a. Geoffrey Homes) "Build My Gallows High." Even though this is considered by many, including our illustrious host Beth Accomando, the quintessential noir; it’s still not as widely seen as it should be. I’ll have a blog post up comparing the film to the book next week.

Heads up about our September read: Unlike most of the books in our series, "Pitfall" by Jay Dratler has never been reissued. If you want to read along, I recommend going to Abe Books and picking up a Popular Library (1956) or Bantam (1949) edition. This will set you back about $15 or $20, but it’s worth it. The film is not to be missed. It’s an overlooked gem about post-war suburban nightmares starring Dick Powell, who you’ll recall from "Murder My Sweet," noir “queen of the B’s” Lizabeth Scott in her favorite role of her career, and the reliably sinister Raymond Burr. Did I say don’t miss it? You’re going to love seeing this film with a crowd at 1 p.m., Sept. 23 at Digital Gym Cinema.

D.A. Kolodenko: Musician. Waiter. Warehouse worker. Print shop manager. College professor. Lecturer. Columnist. Journalist. Editor. Science writer. Advertising copywriter. These are some of the things I’ve been. Detective. Hitman. Embezzler. Boxer. Prison inmate. Fugitive who escapes by running into a tunnel or climbing up something. These are some of the things that the books and movies I like have taught me to avoid being.