At her daughter’s routine check up appointment, Melisa Castro learned that her 3-year-old daughter Michelle could have autism.

“I was a little taken aback … I thought it was more of her personality, but I also didn’t have a lot of education on any of it,” said Castro, whose daughter attends Emerson Elementary School in the Southcrest neighborhood east of Logan Heights.

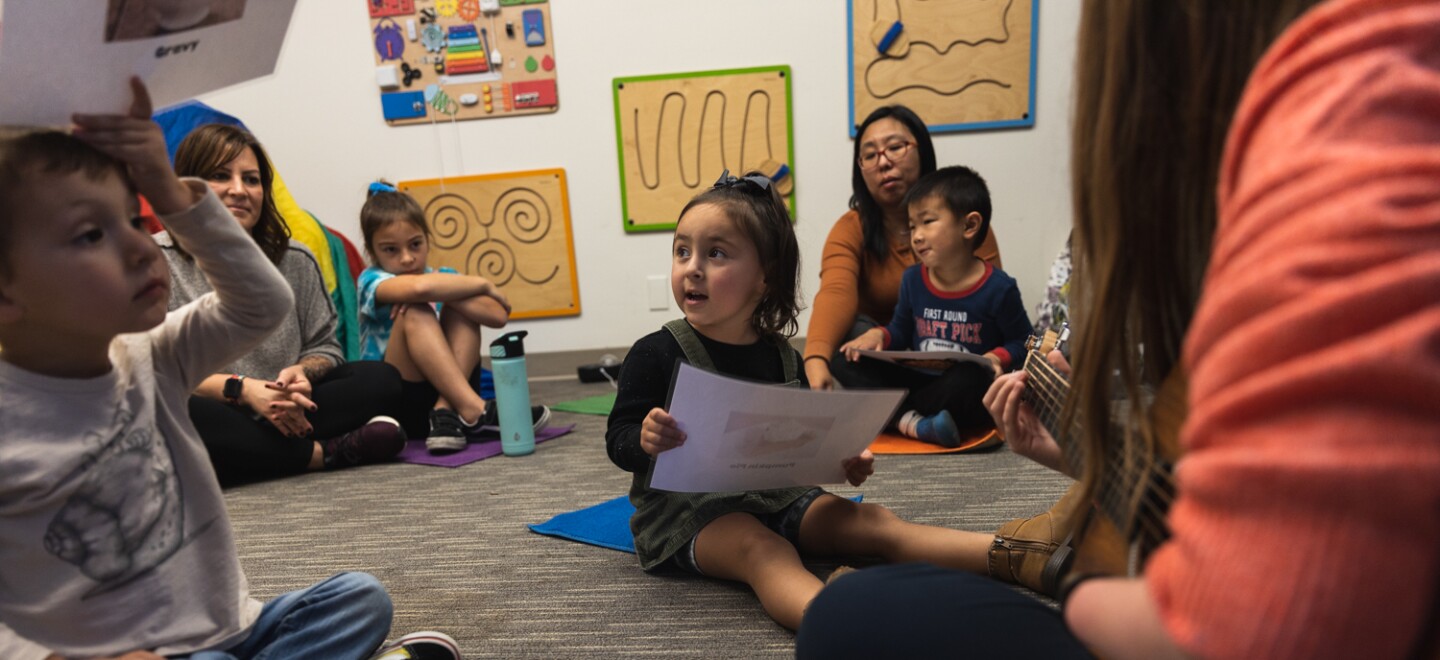

Six months later, Michelle’s pediatrician confirmed the diagnosis, and at the doctor’s direction, Castro asked San Diego Unified to assess Michelle for special education. Early assessment is critical for children like Michelle, so that curriculum can be adjusted to fit their needs.

Yet hundreds of the district's children are waiting a long time for the district to assess whether they need those services -- in fact, many are waiting more than the 60 days allowed by law.

Delays persist as San Diego Unified grapples with a substantial backlog of assessments and more requests for evaluation are submitted. Pandemic isolation may be a driver of increased requests for evaluations, district officials say. And additional staff is needed to meet the demand, but attracting and retaining these professionals is no easy task, the district adds.

San Diego Unified, like other school districts and public agencies, must identify and evaluate children who may have a disability as required by state and federal law – also known as “child find.” However, parents can also submit a request for evaluation to their child’s district, teacher or another school professional.

The district strives to assess children within its boundaries so that when the children turn 3, they can receive special education services and a family education plan, Sarah Ott, executive director for special education at San Diego Unified, told the district’s board of education during a regular special education update at its October meeting.

Once the district receives a request for assessment, parents are notified within 15 days and asked to confirm whether they would like their child to be assessed. After a parent provides written consent, the assessment team has 60 days to evaluate the child, as outlined in the California Education code.

Since the beginning of summer, the district has seen an increase in requests for assessments. In October, the district reported receiving hundreds of requests for assessments and having more than 600 cases outstanding at the time, more than a hundred of which exceeded the 60-day timeline for processing.

Since the start of this school year, the district has completed 560 assessments so far, more than last school year when it only completed 266 by the start of December. But the district vowed to have all overdue assessments completed by the fall and many remain outstanding, Scott Soady, chair of the community advisory committee for special education at San Diego Unified, told board members during the October meeting.

Earlier this month, the district said it has received 703 assessment requests so far this school year. It also has 517 requests still outstanding. Of the students assessed this year, only 173 assessments were completed within the 60 day time frame required by law, and 230 were still pending at 60 days or later.

The backlog is due in part to 378 cases from last school year that the district still had to assess when this school year began. As of this month, 64 of those cases remain outstanding; however, some of the cases have had initial assessments and are awaiting an Individualized Education Plan, said Maureen Magee, communications director for San Diego Unified.

Parents do have some recourse if the district has taken longer than 60 days to resolve their child’s case. If the district is over the timeline, parents can file a complaint with the Department of Education, which will conduct an investigation and ultimately order the district to complete the assessment if it's found in violation, said Paul Hefley, a San Diego-based special education attorney.

A child may also be eligible for tutoring, also known as compensatory services, as a result of the delay, but parents may need to prove the delay caused harm and request the services, he said.

“If we're talking about weeks or months of a delay, then you're guiding into the territory where there's some substantial remedy from that,” he said.

Ott, the district’s special education director, said limited opportunities for socialization during the pandemic and increased awareness of autism may be driving the increase. But evaluations for special education have been on the rise, reaching 1,745 in the 2021-22 school year, up from the 2018-19 school year when 1,375 requests were made, according to the district.

“Students, when they’re younger — one, two year olds — being isolated often can cause language delays or developmental delays,” Ott said. “We’re constantly getting requests, so even to this date that number probably has grown.”

The district says this year, full comprehensive assessments are needed the most. Most students are being assessed for speech and language impairment and after being diagnosed with autism.

Autism is a development disorder that affects a child's behavior, including their social and communication skills, said Crystal Sanford, owner and director of Sanford Autism Advocacy Group.

“It just means that your child's brain works differently,” said Sanford. “In some ways, it's amazing and can have some super great strengths and in other ways, little things that are easy for most of us will be hard for your child.”

Early intervention is crucial for all children, but especially children on the spectrum, said Sanford, who’s daughter was diagnosed with autism at the age of 3 like Michelle. While people with autism can have a range of experiences and need different levels of support, Sanford said her daughter was able to receive early services for a year-and-a-half and was able to enter her in general education in kindergarten.

“The child that you see right now, who is melting down, who maybe has no words, you feel they’re never going to potty train, all these things,” she said. “There is hope.”

Although Castro is fairly new to learning about autism, she recognizes the importance of early identification, too.

“Early diagnosis can help the children significantly because it helps them be in an environment that supports their growth as opposed to kind of shocking them or forcing them into a system that doesn’t always support that,” she said.

But that doesn’t mean that the process of getting your child evaluated is easy, emotionally or otherwise, she said.

“There’s a part of you that’s almost mourning the loss of your child because your mind has a certain expectation of what you think your child will be,” she said. “But now obviously we don’t feel that way. We recognize that this diagnosis is only going to help us take advantage of the resources that are available.”

Staffing shortfalls driving backlog

As San Diego Unified’s assessment backlog grows, the district says staffing shortages are partly to blame. Scheduling conflicts and illness among families and staff are also among the reasons, Magee said.

This past summer, 90 San Diego Unified employees and vendors volunteered to conduct assessments. Assessment teams are made up of a variety of professionals, depending on the type of evaluation the child needs. Teams could include speech language pathologists, school psychologists, occupational and physical therapists, and early childhood teachers.

In an effort to serve families in a more timely manner, the district increased the number of assessment teams from six to nine. Assessment teams typically work Monday through Friday during normal school hours, but now they’re also working afterschool and on weekends to meet the demand, Magee said.

- San Diego Unified teachers reach agreement with district, call off Feb. 26 strike

- Four San Diego Unified Schools named finalists for 2026 America’s Best Schools

- In 'Roots and Blossoms,' San Ysidro High School artists explore their pasts and futures

- U.S. colleges received more than $5 billion in foreign gifts, contracts in 2025

Sanford, who spent 14 years working at San Diego Unified as a speech pathologist, said even when she worked there, staff would be asked if they could work over the summer to catch up on the backlog.

“Their preschool assessment team is, I would dare to say, just not big enough to handle and support the amount of kids that are coming through these days,” said Sanford, who left the district job last year. “We know that autism has significantly increased in the past year, and as a result, there just needs to be more people available to assist.”

Soady, whose daughter, a second-grader in the district, is visually impaired, told inewsource that staffing issues at the district do make him feel worried. He said it’s difficult to attract teachers to San Diego, where the cost of living is so high, or retain teachers who eventually may want to transfer to other higher-paying districts.

He applauded the district’s move to approve a $10,000 hiring bonus for special education teachers last year, but told board members in October that it’s not enough.

“I want to remind everyone that we’re talking about 3-year-olds, so any delay in services is actually a significant portion of their life,” he said. “More needs to be done though to recruit and even more importantly retain teachers, especially in special education.”