Nations and corporations are jostling for a share of the Arctic — a seemingly barren region that everybody wants to own.

The climate is changing, and so is the business climate, which is evident even when visiting a remote spot north of the Arctic Circle.

This place is home to caribou and wolves — and very few people.

"Everybody comes down to meet the planes. That's just about everybody in town, right there," says Canadian Glen Warner, pointing out the window of a float plane. About 10 people are standing below.

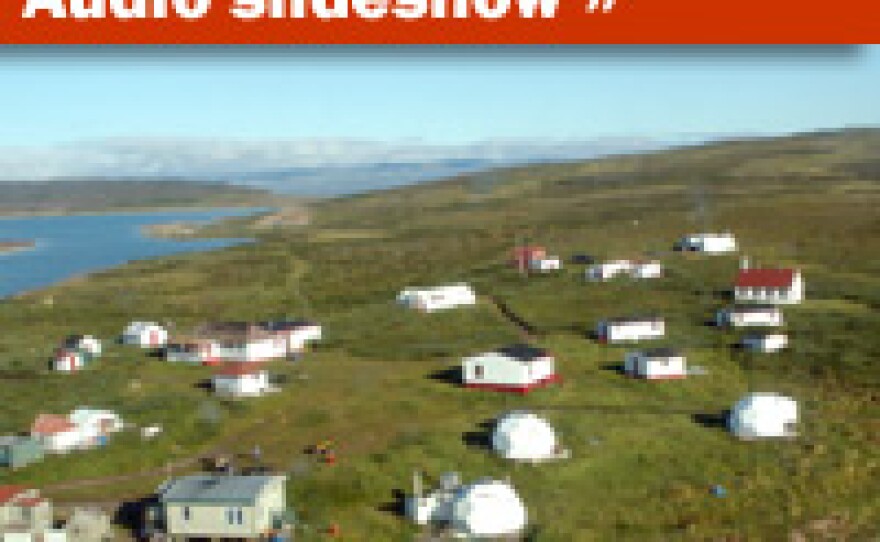

The plane descends to an arctic harbor that's clear of ice in summer. When the pilot splashes down, Warner steps to a dock near the tourist lodge he owns at Bathurst Inlet — a native settlement on the north shore of mainland Canada.

A red-roofed old church rises out of green tundra.

Bathurst is hundreds of miles beyond the nearest highway, but not beyond the interest of business.

Each of the past two summers, the guests at the lodge have included Mike Roberts, who's been working as a geologist.

Last year, a company paid him to come to Bathurst looking for signs of gold. This year, a different company hired him to search for uranium.

Canadian officials pass out maps that show thousands of square miles carved up into mining claims – which provides some indication of why the Arctic is of such interest to governments this summer.

Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper has plans for an Arctic naval base and new Canadian warships. They would defend the Northwest Passage, a sea route that slips right past the opening of Bathurst Inlet.

"Canada's new government understands the first principle of Arctic sovereignty: Use it or lose it," Harper said in a speech Aug. 10.

He wants to use a passage that's famous mainly for the explorers who became trapped in ice there.

Now that seaway offers clear sailing during the lengthening Arctic summer.

Farther north this summer, another country was staking out territory.

A submarine from Russia traveled to the North Pole. The crew planted a flag on the ocean floor and returned home to congratulations from President Vladimir Putin.

"It was a big success for science," Putin said.

But it was also part of Russia's bid to own much of the Arctic Ocean.

Its rivals may include the United States, which recently sent an icebreaker north of Alaska.

Capt. Ted Lindstrom, who leads the Coast Guard cutter Healy, has orders to map the ocean floor, seeking signs that undersea ridges and mountains are technically part of the United States.

The Healy is gathering information just in case the United States joins a treaty called the Law of the Sea, which allows nations to claim much of the ocean floor.

Lindstrom says that's one more factor driving interest in the Arctic.

"The fact that there are concerns about global warming, the fact of increased commercial traffic that could be possible because of the receding ice edge, the mineral rights — those kinds of issues have come together and raised the visibility of many people here in the Arctic," Lindstrom says.

A lot of business could be done on top of the world.

One American who studies these issues sees opportunities as vast as the chunks of polar ice cap that broke apart this summer.

"Less ice means a more accessible Arctic Ocean," says Mead Treadwell, a member of the U.S. Arctic Commission appointed by President Bush.

In his office in Anchorage, Alaska, hangs a map that's oriented so the North Pole is the center of the world.

Surrounding the pole, like rival suitors, are places like Russia and Norway, not to mention the oil-rich state where Treadwell lives.

Look at the world this way, and it's easy to see how the Arctic provides a route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

"The idea that the Arctic Ocean may be as important to global commerce as the Panama and the Suez canals is now a near potential idea," Treadwell says.

One can already sense the possibility of change in Bathurst Inlet — a place where people are accustomed to pulling a very different bounty from the land.

Tony Akoluk is a member of the Inuit nations who have lived on this land for centuries. For him, Arctic ice is good. It lets him go hunting on lakes and streams.

He doesn't need a climate scientist to tell him there's less of it.

"It's warmed up a lot. It's like springtime in December sometimes," Akoluk says.

That thinning ice may delay his hunt in the fall, but it may create opportunities for those hunting Arctic commerce.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))