Along the coast of Peru, a mysterious civilization sprang up about 5,000 years ago. This was many centuries before the Incan Empire. Yet these people were sophisticated. They cultivated crops and orchards. And they built huge monuments of earth and rock.

Archaeologists are trying to prove that an abrupt change of climate created this new culture.

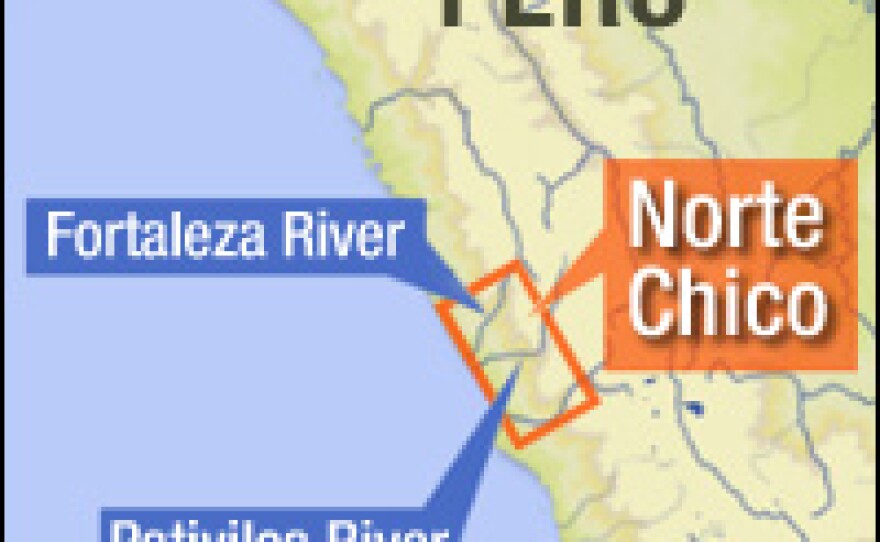

The culture has no official name yet. It flourished in a series of dry coastal valleys called Norte Chico. The place is a moonscape — desolate, misty, a place of rock and dirt, with the occasional cactus and a few hardy trees along the few streams and rivers.

The Mound Builders

What drove people to settle here is something archaeologist Jonathan Haas, of the Field Museum in Chicago, has puzzled over for years.

He doesn't know exactly why they built the mounds he has discovered in Norte Chico. But he has been working on the problem since he first made some unusual finds eight years ago.

"You get down on your hands and knees," he says, showing exactly how he did it years ago, "and what you find is little pieces of seashell. And then you go, 'How do I get little pieces of seashell out here?' And I thought, 'Well, I don't know, I don't know, and I don't really care.' "

But of course he did care.

"I puzzled and puzzled and puzzled over it, and I finally realized it was the people who were building the mounds who were coming out here, and I bet they were fishermen."

Fishermen who had come up from the coast about 10 miles away, bringing shellfish. But why?

The story starts thousands of years ago, when people from eastern Asia flowed into North America and then South America. On a local beach, Haas tells the story.

"People are going where the good resources are," says Haas, a burly, bearded man in his 50s with a wheeze from years of inhaling desert dust. "Right down to this very beach."

This beach is called Barranca. Early Americans — hunters and gatherers — came here to fish and collect mussels and clams. That worked fine until about 3000 B.C., Haas says. "At around 3000, the environment begins to change."

A Change in the El Nino Cycle

Haas suspects that what changed was El Nino, the cycle of warm ocean water and torrential rains that regularly descends on western South America. Some shift in the coupling of the atmosphere and the Pacific Ocean made El Ninos more frequent. Haas doesn't know why it happened, but he believes more frequent El Ninos had a drastic effect on coastal life.

"They were pushing out the cold-water fish," he says of the new El Ninos, "bringing in warm-water fish, killing off local clams and mussels."

The fishing got bad, the weather unpredictable. So people moved inland, to the desert valleys. It was only 10 miles or so, but it might as well have been the moon.

One of the places they went is now called Huaricanga. The ancient people built a mound here about 5,000 years ago. Haas' team is now excavating it. His wife, a professor of archaeology at Northern Illinois Univerisity, is in charge. Winifred Creamer is tall, lanky and soft-spoken. She has a team of students in tow, ready to trowel and shovel away the face of a "profile" — a sheer wall of mound that was created when local farmers dug an irrigation ditch through it.

What they are looking for in this layer-cake of dirt and rock are the remains of floors and walls. There were hearths or fires, too, that show up as dark, burned areas inside the mound. What the team has discovered is that people actually lived on these structures over successive generations.

Working conditions aren't ideal, Creamer says. "We're standing here working outside somebody's house. We're on the edge of the highway, and we're standing in a ditch that may or not fill with water, and the area right behind where we're working is where people throw trash, so it's not really the romance of archaeology, is it?" She laughingly notes that it isn't the kind of place Indiana Jones would work.

A Balance Between Cultures, Old and New

Local people stand above and watch. Alvaro Ruiz, the Peruvian co-director of the project, says these farmers are poor, uneducated but curious about their ancient relatives. But they're also worried about what the digging might do to their life-giving irrigation system.

"We don't want to cause any damage to their irrigation, because people live here, they have many problems, they need to live — that's the point," Ruiz says.

Life was even harder 5,000 years ago. The mound-builders who abandoned coastal hunting-and-gathering and came here had to learn how to grow crops and irrigate them from the precious few rivers and streams. The weather controlled life, especially El Nino.

Standing on a hill, Creamer says El Nino storms would have brought life-giving water, but also destruction.

"You look up this dry wash that we're situated in, and imagine a 40-foot-high wall of water rolling out of that," she says. "That would have a pretty life-changing impact on everybody in this valley."

But people learned a new way of life here in the valleys. Culture grew more complex. Trade flourished. Coastal people brought shellfish — the shells Haas found in the desert — and took back squash and cotton. And they brought their labor to help build the mounds. It was massive architecture on a scale never seen before in the New World.

On a rare sunny afternoon in the Peruvian winter, Haas climbs into a battered SUV and drives out to Porvenir. It's one of dozens of mounds hidden in the creases of the valleys. It's at least 1,000 years older than other mounds in the New World.

A Stone Birthday Cake

Past fields of sugar cane and a network of narrow irrigation ditches, a narrow pass leads to a flat area surrounded by hills. The mound is a pile of rubble, 30 feet high and maybe 200 feet across. Originally, it was terraced, with a flat top, and was the product of enormous labor.

"You have to think of a large stone birthday cake," Haas says with an almost fatherly pride. "And it would have been covered with plaster, and you can have it pink, you can have it light orange." He says the builders would have replastered it regularly, to keep it looking sharp.

Whoever these people were, they built these monuments even before the Egyptians built the pyramids.

On the mound, there are pits dug by present-day looters. Human bones and trash litter the ground. Haas has found precious little jewelry, and this culture made no pottery. Nor has he found weapons.

"This isn't the coolest archaeology in the world in terms of the stuff you find," he says. "There are no beautiful ceramics, no gold masks ... our treasure is trash, residential architecture, and all of a sudden those start bringing together this incredible picture of the origins of civilization in South America."

Haas believes a change in climate started all of this.

"If you think about going from a hunter-gatherer society to this highly centralized society with an organized religion, it's a pretty dramatic change to take place over a very short period of time," Haas says.

There is still a lot of work to do to prove that. Haas is taking sediment cores from a nearby lake that should tell him about climate changes 5,000 years ago. He and colleagues in the United States are studying the rings in seashells he has found. The shells should provide evidence of how ocean temperatures changed during that period.

But whatever this society's genesis, Haas believes its way of life — the mounds, sunken plazas, irrigation agriculture, religion — eventually spread across South America, like a map unfolding.

"There's a very distinctive Andean pattern that starts here and then spreads and forms the foundation for Andean civilization for the next 5,000 years. It's pretty cool," he says.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))