A new phenomenon is spreading through the Christian towns and villages of northern Iraq: Christian security forces, organized through their local churches, are manning checkpoints and working with the Iraqi police.

Many residents are delighted to see Christians standing up to defend themselves. Some, however, worry about the political implications of this latest sectarian armed force in Iraq and wonder where its money is coming from.

A few years ago, Christian churches were being bombed and thousands of Christian families in Baghdad and elsewhere were terrorized into fleeing their homes. Many of them wound up in the north, where they seem to be thriving.

Displacing Iraqi Christians

Qaraqosh is a peaceful town of 50,000 people. But because it's just a few miles east of the northern city of Mosul, one of the most dangerous places in Iraq, security is high.

Every vehicle is stopped, most drivers are questioned, and many cars are searched by members of the Qaraqosh Protection Committee, an all-Christian security force that is spreading to Christian villages across the north.

The coordinator for the Qaraqosh Protection Committee is Sabah Behnem, who says outside agendas — from the Sunnis of al-Qaida to the Shiites in Iran — were behind the brutal efforts to displace Iraqi Christians.

"They thought this community was weak, but it's not," Behnem says. "The evidence is clear: The security violations in our area are very minor."

The protection committee office is bustling. It has the feel of a police station, with officers coming and going, and tips coming in over the phone, except it was founded and organized by church leaders.

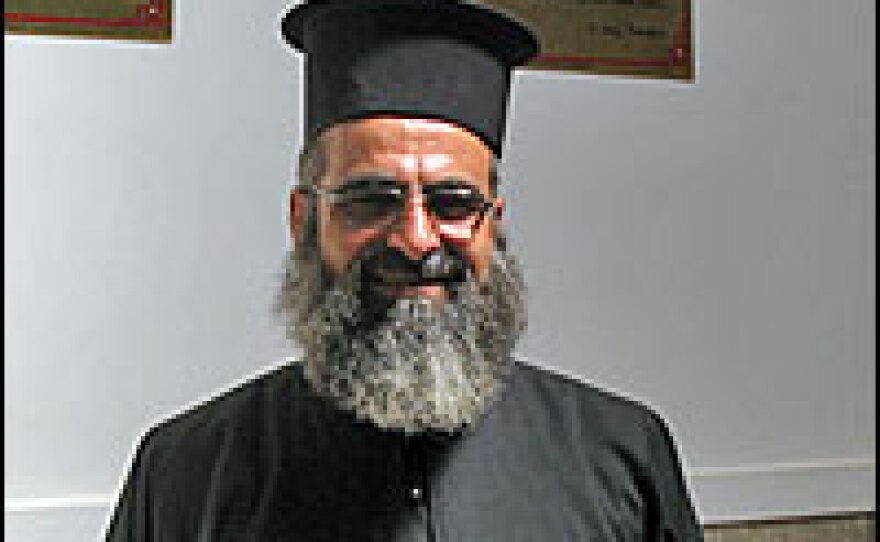

Everyone rises to greet Father Behnam Geggi, the founder of the protection committees. Geggi says the idea germinated back in late 2004, as attacks on Christians escalated.

"After the invasion and the fall of the regime, there was chaos, and we started to think of how we could save this community," Geggi says. "So we did our best to bring security, working with good people who volunteered, and our good brothers the Kurds and, above all, Mr. Sarkis."

Mysterious and media-shy, "Mr. Sarkis" is a key player in this apparently straightforward story of a beleaguered minority learning to stand up for itself, which contains at least two central mysteries: Who is paying for this ever-expanding security force, and what do they expect in return?

Establishing Protection Forces

The ancient Assyrian empire sprang up in this part of the world more than 3,000 years ago. The Assyrians were quick to adopt Christianity, eventually splitting into several branches, including the Chaldeans, Syrian Orthodox, the Church of the East and Syrian Catholics. They may make up a tiny percentage of modern-day Iraq, but they have a fierce commitment to preserving their heritage.

Not far from Qaraqosh, in the village of Bartulla, the market is busy, but that is not necessarily good news for Christian residents. A few years ago, these vendors would be calling out their prices in Syriac, the pre-Christian Assyrian language closely associated with Aramaic. But an influx of Shiite Muslims has squeezed the Christians out, and Arabic now dominates.

Father Daoud Suleiman says the once-Christian village is now evenly divided between Muslims and Christians, and that tensions are getting worse. He says if the church hadn't stepped in and helped create these protection committees, Bartulla would be just another formerly-Christian village:

"After the fall of the regime, things deteriorated," Suleiman says. "We had problems with the Muslims attacking our people. Once the protection forces were established, things got better. Without these forces, supported personally by Mr. Sarkis, Bartulla would be in much worse shape right now."

The Mysterious Mr. Sarkis

Mr. Sarkis seems to be behind every blessing falling on Christians these days.

Villagers say he has single-handedly paid for thousands of salaries — $200 a month for regular members, $350 a month for officers. He has also paid for weapons, vehicles and other infrastructure — and that's just the beginning.

New churches are going up across the north, paid for, everyone says, by Sarkis. New schools, more than 300 new apartments for displaced Christian families from the south, an Assyrian cultural center in Bartulla — the list goes on.

Behnem of the Qaraqosh Protection Committee says that this seemingly endless supply of money comes with no strings attached.

"Mr. Sarkis has given us direct and unlimited support, and he asks nothing in return," Behnem says. "There are no political aims here. He just wants to help Christians stay on their land and preserve their legacy."

Sarkis at first accepted and then declined repeated requests for an interview. Kurdish journalists said that is not unusual — he rarely speaks to reporters. With a little digging, however, some details did emerge.

His full name is Sarkis Aghajan Mamendu, and while his supporters may portray him as a wealthy independent benefactor, he does have a day job that suggests to some where the money may be coming from. He is the finance minister for the Kurdish regional government, and he is a member of the Kurdish Democratic Party believed to be close to Kurdish Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani.

Nazar Hana Patros, with the Assyrian Democratic Movement, says that — with all respect and gratitude to Sarkis — he is bothered by the secrecy surrounding the millions of dollars being spent rebuilding and arming the Christian community.

"We know Mr. Sarkis and respect him, but we know that before the 1990s, he wasn't wealthy," Patros says. "So what is the foreign or regional power that's backing him?"

Converging Minorities

This is where the stories of the tiny Assyrian minority and the much larger Kurdish minority begin to converge — perhaps a bit too closely for some Assyrian nationalists.

Like the Kurds, Assyrians are to be found in northern Iraq, southern Turkey and parts of Iran. Like the Kurds, they have been betrayed by Western powers and brutalized by former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. Perhaps most important, both the Kurds and the Assyrians have long sought their own autonomous region in the north.

This, Patros says, is the problem: Assyrian autonomy means autonomy from the Kurds as well as Iraq's central government.

"We have no problems with the Kurds," Patros says. "They are our brothers on this land. We fought with them against the former regime. But just because we are fewer in number doesn't mean they become our guardians."

Many Christians, as well as Turkmen, Yazidis and other minorities recall bitterly how the Kurdish Peshmerga forces prevented thousands of non-Kurds from voting in 2005, and Christians have no desire to see Assyrian autonomy reduced to a footnote in a Kurdish drive for independence.

On the other hand, some Christian leaders argue, the Assyrians, realistically speaking, have justice but no leverage on their side, and could use all the help they can get.

Meanwhile, the Christian protection committees continue to grow. Their leaders say they want to join the Iraqi police, but like the Sunni Awakening forces to the south, they are finding it slow going.

Geggi says he and his Assyrian, Chaldean and Syriac colleagues are quite comfortable staying involved in the security of their villages for as long as necessary.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))