When earthquakes happen, earthquake scientists want to be there, especially with an earthquake as large and destructive as the 8.8-magnitude quake that hit Chile last month.

In the days and weeks that have followed, geophysicists and geodesists, who study the Earth's movement, have flocked to Chile's "rupture zone," a swath of vineyards and piney hills hammered by the quake.

And more scientists are on the way, with the goal of picking up enough clues to one day predict when the next big one will strike. The country has a propensity for big quakes because of two huge underground plates crashing head on into each other.

Among the first to arrive after the Feb. 27 quake was Jeff Genrich, a German-born geophysicist who works at the California Institute of Technology. With airports closed in Chile because of the quake, he flew to neighboring Argentina and then crossed the Andes overland.

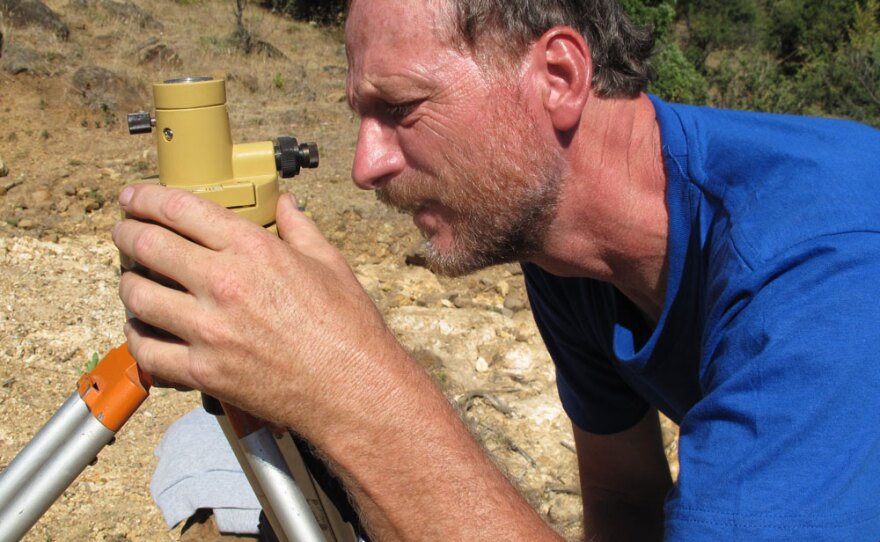

On a recent day, with a searing sun beating down, he tramped up the rocky foothills of the Andes not far from the hard-hit city of Talca.

Accompanied by a university engineer and an official from the Military Geographic Institute, Genrich's task was to install a sensor to measure the big aftershocks that have been rattling this ribbon-shaped country.

The data being collected by earthquake scientists is being used to help them reach what Genrich calls "the Holy Grail."

Most of us are still awed by the size of it.

"The Holy Grail is to be able to predict an earthquake," Genrich said. "And to somehow at least say, OK, it's going to happen at this and this location, and it has this and this magnitude. So people that are within this zone should be evacuating their homes, should be out in the open where nothing can hurt them."

Chile has been rattled by dozens of aftershocks, one of which was 6.6 magnitude. The fact that the aftershocks have been so big gives scientists who have rushed here — many of them from the United States — the chance to more precisely measure exactly how the ground is shaking.

"It's very exhilarating," said Michael Bevis, a professor of geodynamics at Ohio State University who has been studying ground movements here for 17 years. "I think there are a lot of people running now mainly on adrenaline."

Bevis should know. He has been in Santiago, the capital, organizing logistics and raising money as he sends team after team of scientists into the earthquake zone.

"Time is very precious," he said. "If you don't get there until, say, two or three weeks afterwards, you've missed an important part of the signal."

Even scientists in the United States are watching closely, like Dana Caccamise, a geophysical engineer who designs many of the sensors earthquake specialists use. From Ohio State, he has been closely monitoring what his colleagues have been doing.

"Most of us are still awed by the size of it," he said. "The race we're having is to get down there."

Indeed, the quake was so big that NASA scientists believe it sped up the rotation of the Earth, possibly making the day about a millionth of a second shorter.

Ben Brooks, director of the Pacific GPS Laboratory at the University of Hawaii's School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, estimates that the quake moved part of Chile 3 meters — about 10 feet — to the west. Even faraway Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina, moved up to 4 centimeters, Brooks said.

Geophysicists and geodesists are now roaming all over the Bio Bio and Maule regions, two of the hardest hit, putting up sensors. Brooks said that Chile, which has an advanced scientific community, already had about 50 data collection stations up and down the 2,800-mile-long country. But he said he is hoping that as many as 25 more sensors are put up in the area where the quake caused the most damage.

"This is going to be arguably the best-measured great earthquake," Brooks said.

This is going to be arguably the best-measured great earthquake.

Genrich has already been doing his part, installing a sensor on a rocky bluff overlooking the Pacific and also farther inland, including here in a region where pine forests carpet the mountains.

"Sometimes it may take quite some time to find these points," he said, breathing hard as he and his team made their way up.

They were searching for a tiny, stainless steel pin embedded in the bedrock years before by Chilean technicians. He said that pin, the size of a nail and installed in 1992, would be measured using a GPS receiver. The idea is to determine how much the pin — and the Earth around it — moves with each aftershock.

"This is what we're looking for, this little stainless steel pin in the ground, of diameter of a fingernail, the size of a fingernail," he said, moments after his team found the steel dimple.

Genrich said the instruments permit scientists to pick up seismic events "that produce motion larger than a millimeter."

There could be nothing obstructing the GPS receiver — which collects signals from a satellite, he said. Genrich and his team steadied the tripod that holds the receiver with big rocks — to keep it in place in case some wandering cow decides to rub up against it.

Genrich said that scientists have come a long way from the days when pendulums were used to measure the shaking Earth. Now, with high-tech instruments and satellites, they can assign probabilities for when a quake might strike.

But Genrich said they can still not say with certainty when the next big one will hit, and that is the goal, if lives are to be saved in the future. In Chile, that means looking for as much data as possible.

"That's why we're scientists," he said. "We like to collect the data, we like to analyze it, because we like to understand what's going on there."

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))