A hand-held shovel is jammed into the dirt at the edge of one of San Diego’s coastal wetlands. The goal is separating a fully grown cattail from its home.

“You can see how hard it is to dig out,” said Joseph Noel, a researcher at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies. “That’s why it holds the sediment extremely well. And so there’s very little erosion.”

RELATED: San Diego Researchers Looking To Grow A Climate Solution

Joseph Noel watches his colleague Todd Michael lift up the plant.

“Oh, here’s a nice shoot coming up,” Noel said.

The pair of San Diego researchers are working with cattails as part of the Salk Institute’s Harnessing Plants Initiative, a far-reaching effort to tap the potential of plants to help stave off the worst impacts of global warming.

RELATED: Researchers Find How Venus Flytrap Plants Can React To Touch

On this day they are digging in San Diego’s Batiquitos Lagoon, a coastal wetland right beside one of the region’s busiest highways, Interstate 5. The steady din of passing traffic is completely ignored as the scientists gently examine the four- to five-foot-long stalks.

Michael, a biological geneticist at the Salk Institute, jams the shovel through the cattail’s interconnected roots and into the softer sediment. A hard pull separates the plant from its anchor but it still clings to a clump of rich wet dirt.

RELATED: New Habitat Preserve In North San Diego County Helps California Gnatcatcher

The dark mud is created by the constant push and pull of this coastal wetland environment. Saltwater regularly flows into the estuary, pushing back and even killing the freshwater cattails. When freshwater dominates, the cattails thrive.

The constant cycle of fresh, salty, and sometimes lack of water, creates a cycle of life and death that builds a bed of carbon-rich sediment.

Michael’s hands clean sticky black mud off the base of a cattail stalk.

“Yup, it’s an example,” Michael says as he handles the plant’s roots. “It’s still alive, so you can see a new shoot is forming off of the rhizome here. So, this is the rhizome.”

The rhizome is an underground stem that grows sideways, much like roots of grass found in Southern California yards. But that’s not what Noel is interested in.

“Turns out that wetland plants,” Noel said, “plants that have wet feet, either like this or even fully submerged; they make a lot of suberin, particularly in their roots.”

And suberin has the Salk team’s attention. Suberin is a cellular material that acts as a protective barrier on small rootlike extensions, letting fresh water in and keeping salt water out.

And the little suberin-covered appendages are full of carbon molecules.

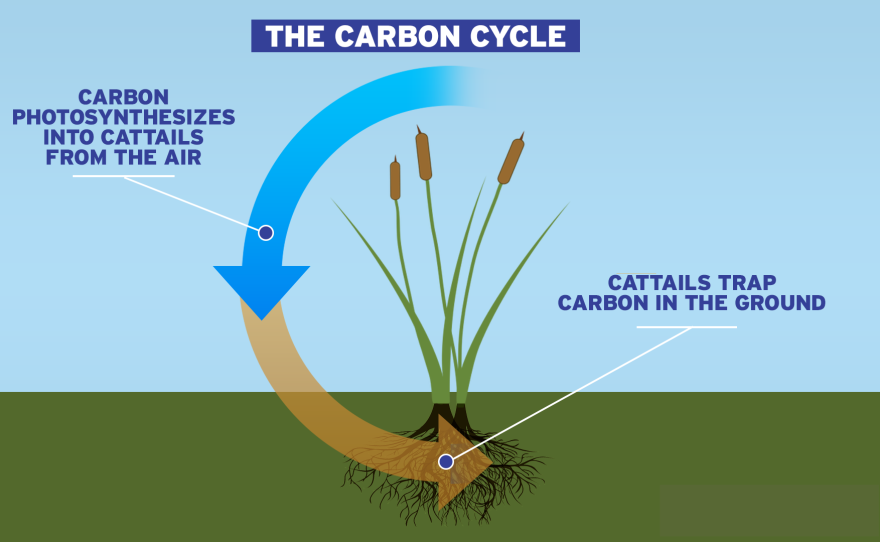

“Plants are naturally carbon accumulating machines, right,” Michael said.

“They suck carbon dioxide out of the air. All this right here,” he said as he grabbed the plant’s stem. “All this biomass is basically just carbon. That carbon gets transferred to the roots when it dies back like this. It gets stored in the soil, naturally. This is one thing that already happens.”

And the carbon molecules in suberin don’t break down when the plant dies; rather, the carbon stays in the thick sediment where it is constantly covered by newly dead plants.

“You can almost see it,” Noel said. “It’s very dark and black. So it’s full of carbon. In fact, I bet if you dug down, up to 10 feet below this, depending how long this existed, it would be a huge amount of carbon that is stored, relative to what would happen on dry land where you have a lot of erosion. That’s another reason why wetlands are so efficient because they continually build up more and more carbon.”

Noel and Michael sequenced the cattail genome and they hope to transfer the plant’s ability to make suberin into crop plants like corn and sorghum.

“With these new gene editing technologies,” Noel said, “We really think we’re going to be able to go into these crop plants and tweak them to make them more like typha (cattails) so the roots will have more of this substance.”

The impact could be huge.

Crop plants with the modified roots could pull as much as a quarter of the planet’s excess carbon out of the air. That’s enough to have a real impact on climate change.

And typha has other traits that could make crop plants more resilient.

“Each cattail makes 300,000 plus seeds," said Michael. "If you’ve ever seen a cattail release its seeds, it looks like snow. And all of those seeds have the potential to be a new stand of typha.”

But the habitat that is so efficient at storing carbon has been under assault for decades. Urbanization has eliminated 90% of the state’s coastal wetlands.

“There’s been a big change with people,” said Darren Smith, a senior environmental scientist with California State Parks. “I think wetlands were something, almost like an oasis early on in California where you just didn’t run into fresh water very often. And when you did it was a life saver.”

And those same wetlands that are giving researchers hope about slowing climate change are under a lot of stress.

People are making it hard for the habitat to adapt.

“We built right up to them,” Smith said. “We build up the watersheds and we built right up to the edges of them. And so, for them to do what they do, to retreat or for the water to back up and form new vegetative wetlands further upstream, there’s just got to be the space to do it.”

Researchers say giving the habitat that space also gives scientists extra time to find other plant-based keys that could play a role in reducing the speed of climate change.