Just after noon on June 21, 2021, a staffer in Councilmember Raul Campillo’s office had a text exchange with a staffer in Councilmember Joe Lacava’s office.

“So nice to meet you today! I'm shocked your (sic) a campaign person,” Jared Miller-Sclar wrote to Kaitlyn Willoughby.

“I know I am young but if I am following in your footsteps that is definitely a great sign because you have done some great things,” Willoughby responded.

Then Miller-Sclar, who at the time was Campillo’s spokesperson, gave his junior colleague some advice: download the messaging app Signal. He even sent her a download link.

What is Signal?

What makes Signal different from other messaging like texts is that it’s fully encrypted, meaning messages can’t be downloaded or shared, even under subpoena. It also has a “disappearing messages” setting, where messages can be automatically deleted in as short a time as 30 seconds.

“Def download signal, its (sic) preferable for me for communicating about campaign/work stuff, or of course just the tea,” Miller-Sclar wrote.

This exchange over standard text messaging was among disclosures from Campillo’s office in response to a California Public Records Act request made by KPBS. Miller-Sclar’s admission that he was using Signal for communicating about "work" should mean his Signal messages are public records. State law says that most communications about government business must be made available to the public.

However, when KPBS asked Miller-Sclar for his Signal messages about government business, he said he had none to disclose. Lacava’s office also said Willoughby had no Signal messages about government business.

Bright red flags

This raises bright red flags for lawyers and experts in California’s public records laws, who say government employees should not be communicating about public business on an encrypted messaging app because there’s no way to check whether the communications should be made public.

When the state Public Records Act became law in 1968, nearly every disclosable record was printed on paper. Fast forward more than a half-century and the vast majority of records are in electronic form and the public’s business can be done on an array of communication platforms including email, social media, Slack and other messaging apps. It opens endless avenues for public officials to try to keep secret information that the public has a right to know, say open government advocates.

“It tips a balance that's already in favor of the holder of the records, meaning the public agency, because the agency has knowledge of what records exist,” said Shaila Nathu, a lawyer for the open government advocacy group Californians Aware. “And in the vast majority of requests, the public doesn’t know whether the requested records exist or not, to what extent they exist … it decreases the public’s ability to hold its government to account.”

Signal is especially concerning because it is specifically designed for secret communications, Nathu said. It requires the public and the media to trust that government agencies are actually handing over all the public records produced by their employees.

“It's a means of avoiding disclosure to the public, and it flies in the face of transparency and government accountability,” she said. “Government employees should not be able to use Signal to carry out their work as public servants. There should be policies in place at the public agencies preventing (government employees) from using Signal to conduct government business on any device.”

Signal’s delete option is particularly alarming, Nathu said.

“After they're deleted, there's no record of that communication on either the actual device or on the server, and that renders a search for public records impossible,” she said.

Miller-Sclar declined to do an interview for this story, but answered questions by email. He said people in Campillo’s office do use Signal, but on their personal phones and not for communicating about government business.

In a statement to KPBS explaining his texts to Willoughby, Miller-Sclar said the communication was “an in-person conversation with Ms. Willoughby, another city employee, outside of work hours and away from city hall, to discuss possible political and campaign efforts in the future. The context of Mr. Miller-Sclar’s messages shows that Ms. Willoughby wanted to be more involved in campaigns and he was inviting Ms. Willoughby to discuss those matters specifically over Signal.”

However, Miller-Sclar’s texted about using Signal for “communicating about campaign/work stuff,” not just campaign efforts, and he sent those messages just after noon on a Monday.

Records show other staffers in Campillo’s office also use Signal. KPBS requested any records that contained the phrase “on Signal,” and received several.

For example:

However, despite all of these references to Signal, Campillo’s office told KPBS that there were no Signal messages about government business to or from any of those employees to disclose.

When KPBS asked in an email whether those mentions of Signal meant employees were using Signal for government communication, Campillo’s chief of staff, Michael Simonsen, responded by saying: “We will not be commenting further on this issue.”

As of early May, Miller-Sclar stopped working for the city.

Willoughby’s texts with Miller-Sclar were the only references to Signal made in communications among staffers in San Diego City Council offices other than Campillo’s, according to responses to KPBS Public Records Act requests.

That said, some offices told KPBS that their employees may use Signal on personal phones. Councilmember Chris Cate’s office said “some employees may utilize Signal for personal use” and Councilmember Monica Montgomery Steppe’s office said they don’t monitor what apps employees have on their personal phones. Most offices said they use email, text, Zoom and Microsoft Teams for communications.

A spokesperson for San Diego Mayor Todd Gloria said no one in their office uses Signal for work-related communication.

The picture in one San Diego County office is different. Supervisor Nathan Fletcher’s office uses Signal constantly for communication about government business.

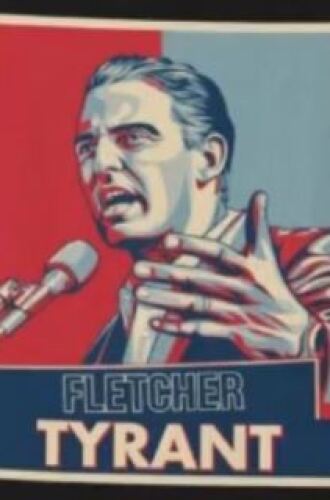

Fletcher’s team has a group text on Signal called “NO NATHAN — All Staff” where they communicate about all manner of things from a staffer asking for the office key code to talking points for Fletcher’s State of the County speech. The office has another group text called “All Staff w/ Nathan,” with a Shepard Fairey-style illustration of Fletcher with the words “Fletcher Tyrant.”

Fletcher’s office provided all of those Signal messages in a response to a KPBS records request.

Fletcher’s spokesman James Canning declined an interview request but answered questions by email. He said Signal is used on “a mix of personal and county devices, but any county work conducted on any device is subject to all county retention policies” and that no one has autodelete settings turned on.

Canning wouldn’t answer directly whether his office includes Signal messages in its responses to other public records requests, instead referring the question to Michael Workman, the county’s chief spokesperson.

Workman said he hadn’t heard of Signal prior to KPBS’s question, but said that going forward: “County employees are required to provide all responsive records of county business regardless of the platform or account in which they are kept. This would include Signal or any other platform used to send communications of county business.”

He added that “communications generally are not required to be retained by law,” but that the county is working on new retention rules.

New laws needed

Despite the apparent openness of Fletcher’s team regarding their Signal use, the use of the app for government business is still troubling to David Loy, the legal director of the First Amendment Coalition. He said it would be much more straightforward for government employees to keep their communication on the government’s own messaging systems like email, which can be easily searched if there’s a public records request.

“But if a substantial amount of those messages are on private channels, the agency's task and burden becomes that much more difficult, because then they have to … not only search their own systems, but also require employees to search their own systems and their own channels and produce those documents, which they have a legal obligation to do,” Loy said.

“If they wanted to avoid that problem they could have a clear, bright-line which says, if you're doing public business do it on the public agency's own system and you can use Signal or Instagram or other direct messages for your own personal business.”

Loy was even more troubled by the response from Campillo’s office, where messages made it seem clear employees were using Signal but then the Signal messages weren’t disclosed.

“The execution and operation of the Public Records Act does depend to a large degree on an agency's good faith,” he said. “The California Supreme Court presumed the agencies would act in good faith. And if they are not, that undermines and defeats the purpose of the entire system of open government.”

While Loy acknowledges the limits of the Public Record Act, he applauds its 1968 authors for writing it in a way that anticipated the coming information revolution. “The definition of what constitutes a record is stunningly and brilliantly prophetic that it was so broad,” he said.

As such, Loy thinks today’s lawmakers need to address the challenge that apps like Signal present by focusing on stronger records retention laws rather than rewriting the Public Records Act.

“There is not a standardized rule across the state over retention of records,” Loy said.

A bill from 2019, written by Gloria when he was a member of the state Assembly would have set a standard record retention rule for local government agencies. But Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed that bill. Now the Assembly is considering another bill that would require just state records to be retained for two years.

Loy said on top of standardized records retention rules, the legislature should pass laws stating “that public business should be done on public platforms, full stop.”

“At the very least a public account must be copied on public business, which avoids the problem of having to search private devices,” he said. “And there should be a clear rule that public business should not be done on applications that have disappearing messages.”

As far as Loy is aware, there is no legislation currently in the works on either of those fronts.

Even without state action, local governments are free to adopt strict rules on the use of messaging apps by their employees. But the record is mixed in San Diego County.

The county’s IT policies do not require employees to get approval of applications before using them, even on government-issued phones. It does, however, require employees to follow certain rules, including retaining records and not sharing private information.

The city of San Diego does require employees to get approval before installing applications on city-issued phones, and so far no one has been approved to use Signal, said Darren Bennett, the city’s chief information security officer.

Employees are allowed to use personal phones for city business, but the city uses an application to manage the work-related business — like accessing work email — done on the personal phone.

The bigger issue, said Nathu with Californians Aware, is that the public wouldn’t know whether government employees are using Signal at all without evidence like what KPBS obtained — emails and text messages that mention talking offline on Signal.

“It’s like 'Fight Club,'” she joked. “I feel like the first rule of using Signal as a public official should be: don't mention that you use Signal.”

-

Records show staffers for local office holders use the encrypted messaging app Signal. Experts say this circumvents California’s public records law because there’s no way to check whether records that should be made public are actually disclosed.

-

This year’s point-in-time count by the Regional Task Force on Homelessness found increases in the number of senior, disabled and Black San Diegans who are living without permanent shelter.