Army studies show that at least 20 percent to 25 percent of the soldiers who have served in Iraq display symptoms of serious mental-health problems, including depression, substance abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Administration officials say there are extensive programs to heal soldiers both at home and in Iraq.

But an NPR investigation at Colorado's Ft. Carson has found that even those who feel desperate can have trouble getting the help they need. In fact, evidence suggests that officers at Ft. Carson punish soldiers who need help, and even kick them out of the Army.

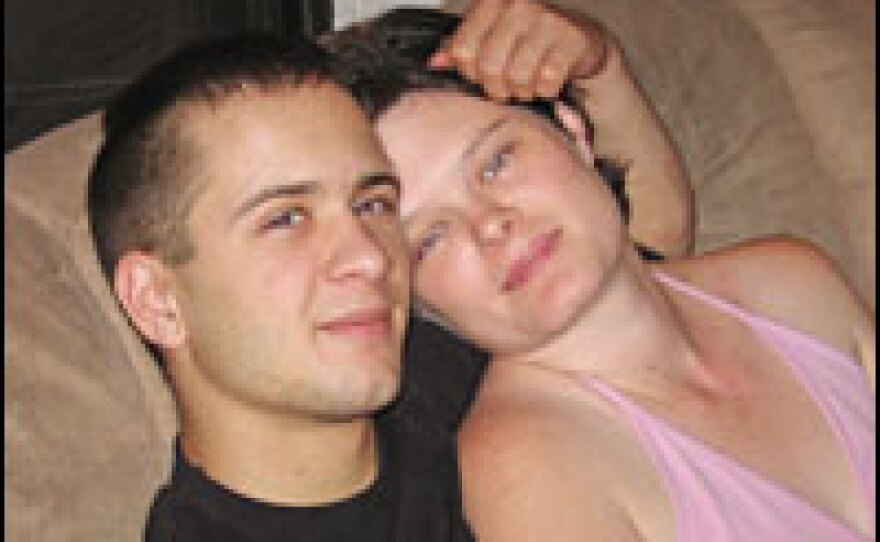

Soldier Tyler Jennings says that when he came home from Iraq last year, he felt so depressed and desperate that he decided to kill himself. Late one night in the middle of May, his wife was out of town, and he felt more scared than he'd felt in gunfights in Iraq. Jennings says he opened the window, tied a noose around his neck and started drinking vodka, "trying to get drunk enough to either slip or just make that decision."

Five months before, Jennings had gone to the medical center at Ft. Carson, where a staff member typed up his symptoms: "Crying spells... hopelessness... helplessness... worthlessness." Jennings says that when the sergeants who ran his platoon found out he was having a breakdown and taking drugs, they started to haze him. He decided to attempt suicide when they said that they would eject him from the Army.

"You know, there were many times I've told my wife — in just a state of panic, and just being so upset — that I really wished I just died over there [in Iraq]," he said. "Cause if you just die over there, everyone writes you off as a hero."

Services Out of Reach for Soldiers

Jennings isn't alone. Other soldiers who've returned to Ft. Carson from Iraq say they feel betrayed by the way officials have treated them. Army files show that these were soldiers in good standing before they went to Iraq, and that they started spinning out of control upon their return.

Since the war in Vietnam, military leaders have said that soldiers who are wounded emotionally need help, just like soldiers missing limbs.

"The goal, first and foremost, is to identify who's having a problem," says William Winkenwerder, assistant secretary of defense for health affairs. "Secondly, it's to provide immediate support. And finally, our goal is to restore good mental health."

The Army boasts of having great programs to care for soldiers. The Pentagon has sent therapists to Iraq to work with soldiers in the field. And at Army bases in the United States, mental-health units offer individual and group therapy, and counseling for substance abuse. But soldiers say that in practice, the mental-health programs at Ft. Carson don't work the way they should.

For instance, soldiers fill out questionnaires when they return from Iraq that are supposed to warn officials if they might be getting depressed, or suffering from PTSD, or abusing alcohol or drugs. But many soldiers at Ft. Carson say that even though they acknowledged on the questionnaires that they were having disturbing symptoms, nobody at the base followed up to make sure they got appropriate support. A study by the investigative arm of Congress, the Government Accountability Office, suggests it's a national problem: GAO found that about 80 percent of the soldiers who showed potential signs of PTSD were not referred for mental health follow-ups. The Pentagon disagrees with the GAO's findings.

Soldiers at Ft. Carson also say that even when they request support, the mental-health unit is so overwhelmed that they can't get the help they need. Corey Davis, who was a machine gunner in Iraq, says he began "freaking out" after he came back to Ft. Carson; he had constant nightmares and began using drugs. He says he finally got up the courage to go to the Army hospital to beg for help.

"They said I had to wait a month and a half before I'd be seen," Davis said. "I almost started crying right there."

Intimidated by Superiors

Almost all of the soldiers said that their worst problem is that their supervisors and friends turned them into pariahs when they learned that they were having an emotional crisis. Supervisors said it's true: They are giving some soldiers with problems a hard time, because they don't belong in the Army.

Jennings called a supervisor at Ft. Carson to say that he had almost killed himself, so he was going to skip formation to check into a psychiatric ward. The Defense Department's clinical guidelines say that when a soldier has been planning suicide, one of the main ways to help is to put him in the hospital. Instead, officers sent a team of soldiers to his house to put him in jail, saying that Jennings was AWOL for missing work.

"I had them pounding on my door out there. They're saying 'Jennings, you're AWOL. The police are going to come get you. You've got 10 seconds to open up this door,'" Jennings said. "I was really scared about it. But finally, I opened the door up for them, and I was like 'I'm going to the hospital.'"

A supervisor in Jennings' platoon corroborated Jennings' account of the incident.

Disciplined, Then Purged from the Ranks

Evidence suggests that officials are kicking soldiers with PTSD out of the Army in a manner that masks the problem.

Richard Travis, formerly the Army's senior prosecutor at Ft. Carson, is now in private practice. He says that the Army has to pay special mental-health benefits to soldiers discharged due to PTSD. But soldiers discharged for breaking the rules receive fewer or even no benefits, he says.

Alex Orum's medical records showed that he had PTSD, but his officers expelled him from the Army earlier this year for "patterns of misconduct," repeatedly citing him on disciplinary grounds. In Orum's case, he was cited for such infractions as showing up late to formation, coming to work unwashed, mishandling his personal finances and lying to supervisors — behaviors which psychiatrists say are consistent with PTSD.

Sergeant Nathan Towsley told NPR, "When I'm dealing with Alex Orum's personal problems on a daily basis, I don't have time to train soldiers to fight in Iraq. I have to get rid of him, because he is a detriment to the rest of the soldiers."

Doctors diagnosed another soldier named Jason Harvey with PTSD. At the end of May this year, Harvey slashed his wrists in a cry for help. Officials also kicked Harvey out a few months ago for "patterns of misconduct."

A therapist diagnosed Tyler Jennings with PTSD in May, but the Army's records show he is being tossed out because he used drugs and missed formations. Files on other soldiers suggest the same pattern: Those who seek mental-health help are repeatedly cited for misconduct, then purged from the ranks.

Most of these soldiers are leaving the Army with less than an "honorable discharge" — which an Army document warns "can result in substantial prejudice in your civilian life." In other words, the Army is pushing them out in disgrace.

Anne Hawke produced this report for broadcast.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))