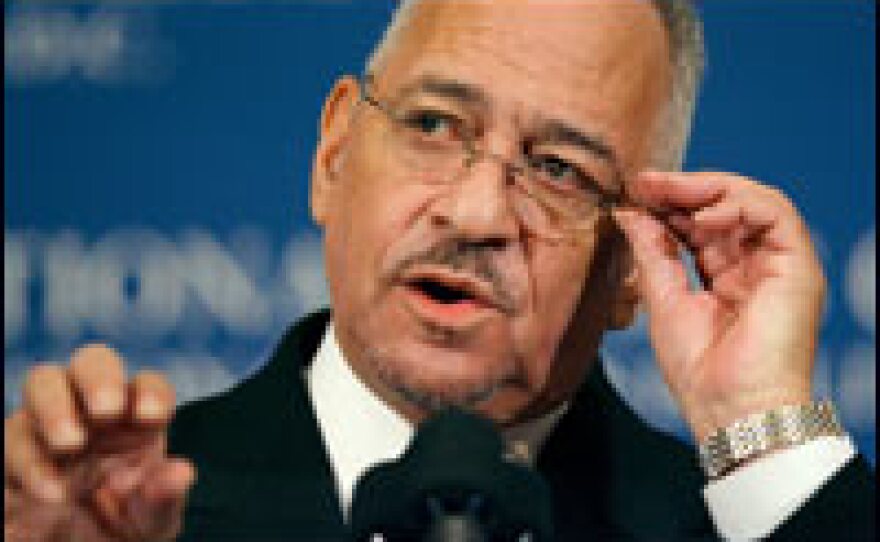

When Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Barack Obama's longtime pastor made his flamboyant appearance at the National Press Club on Monday, he returned to one theme over and over again. The controversy, the Rev. Jeremiah Wright said, was not about him or his statements.

"This is not an attack on Jeremiah Wright," he said. "It has nothing to do with Senator Obama. This is an attack on the black church launched by people who know nothing about the African-American religious tradition."

The Rev. Graylan Hagler was sitting in the audience, watching his friend defend himself. Hagler is the senior pastor of Plymouth Congregational United Church of Christ in Washington, D.C. He says decrying injustice and criticizing ruling powers is what black preachers do, and he believes the controversy has been manufactured to stop preachers from doing so.

"It is an attack on the black church — to muzzle us to silence the preaching and the power of that form of teaching and preaching and action in the world," Hagler says.

Hagler says many black preachers and congregants echo Wright's assertions. He has preached that the U.S. government invited the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks because it has performed acts of terrorism on other countries.

Hagler says given the government's past actions – for example, withholding penicillin from blacks afflicted with syphilis in Tuskegee, Ala. – many African Americans do believe the U.S. government developed the HIV virus to kill people of color, as Rev. Wright has asserted.

Hagler says he supports Obama. But he says if Wright's statements harm Obama's bid to become the first African American with a shot at the presidency, "chips fall where they may. As every preacher will tell you, the thing they're accountable to is God Almighty."

'A Judas Kiss'

But Bishop Harry Jackson of Hope Christian Church in Beltsville, Md., has another take on Obama's pastor.

"Jeremiah Wright is not mainstream," Jackson says.

Jackson leads a Pentecostal church, which focuses on self-improvement and helping people join the middle class. And while the church cares for the poor, it has little theologically in common with the Rev. Wright's focus on injustice and oppression.

"He doesn't represent the majority," Jackson says. "My guess is maybe 25 percent of black pastors may hold that view. So you've got a gifted communicator with what I would call a flawed world view."

Jackson was also shocked that Wright violated his pastoral relationship with Obama by revealing information about private conversations. And Jackson says he believes Wright knew he was torpedoing Obama's campaign.

"For him to speak up now," Jackson says, "was, in fact, a Judas kiss."

Different Wings

These conflicting views of Wright appear to reflect a larger truth.

"The black church is very complicated," says Frederick Harris, who teaches about politics and African-American society at Columbia University.

"It has its Pentecostal prosperity wing. It has the more conservative elements among traditional black Baptists. It has its liberation theology wing. So to speak about a black church is a misnomer," Harris says.

Beyond that, Harris says, Obama's campaign undercuts the role of many black institutions, including black churches like Wright's, that stand outside of, and critique, mainstream politics.

"Given what we know about Jeremiah Wright," Harris says, "I believe he's really impatient with the whole deracialized strategy – one that emphasizes need for racial unity and deemphasizes the role of racism in American society."

For civil rights veterans like the Rev. Ronald Braxton, the fight between Wright and Obama is heartbreaking. The senior pastor at Metropolitan AME Church in Washington, D.C., subscribes to Wright's theology. But, he says, "I'm not sure that at this moment, Jeremiah Wright has a view of the greater cause. And the greater cause, of course, is the nomination of Barack Obama."

But if Obama fails, Braxton says, it won't be Wright's fault.

"He may be blamed, but he won't be the cause for the downfall. The system would have found a way," Braxton says.

Taking Time to Pray

Would Braxton, like Wright, ever say "God damn America" in a sermon?

He shook his head. "I don't know one black preacher who would use that term on Sunday morning."

Nor would it happen in a Wednesday noon sermon, when 35 or so people — some white, most black — gather at the Metropolitan church sanctuary for a midweek service. They sway and clap and even cry during the worship service. Later, several stand to share testimonies of prayer and thanks.

Congregant Hosiah Huggins echoes comments of others when he said he doesn't blame Obama for cutting ties with his former pastor. It pains him to say so, because he has been to Wright's church and admires the work he does for the poor.

Huggins says he feels Obama "had to separate himself because he has a public responsibility to a major constituency" rather than to Rev. Wright's church.

Associate Pastor Kimberly Barnes sees this as a personal tragedy with national implications.

"I think Obama felt wounded, I think Rev. Wright also feels wounded and a need to respond. But I think it's very unfortunate and I really don't like to see them pitted one against each other," Barnes says.

Joanne Clark Booker, who sang at the mid-day service, just lifts her eyes to heaven.

"I think at this particular point, we all just need prayer" — to move past this public rift between the pastor and his former congregant, Booker says.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))