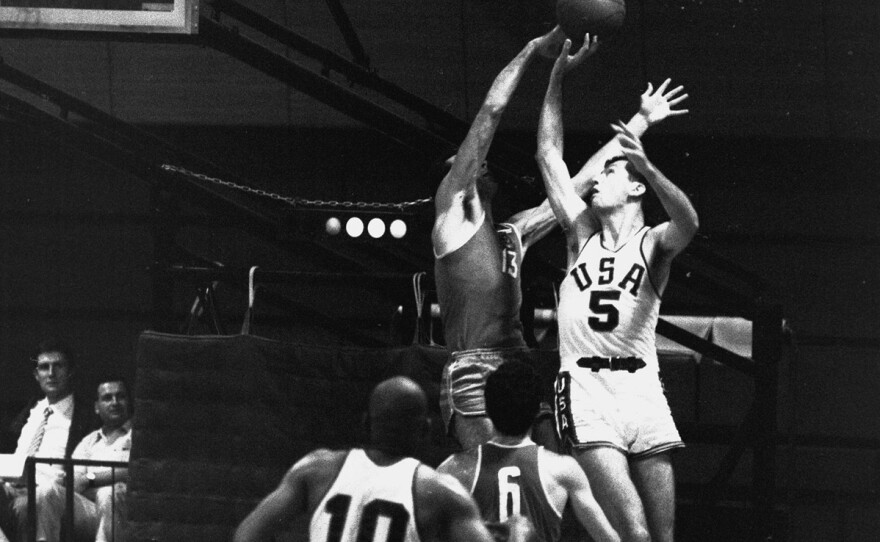

Ralph Metcalfe and Jim Ryun sprinted. Bob Mathias ran, tossed, and jumped. Bill Bradley dribbled. Wendell Anderson defended. Ben Nighthorse Campbell judo chopped.

They competed in different Olympic sports and in different eras, but they had one thing in common: they all ran for Congress and won.

Some of them ended up in the House. Others landed in the Senate.

The Olympics, it turns out, can be an outstanding platform for athletes who'd like to remain in the public eye long after their career in sports is over.

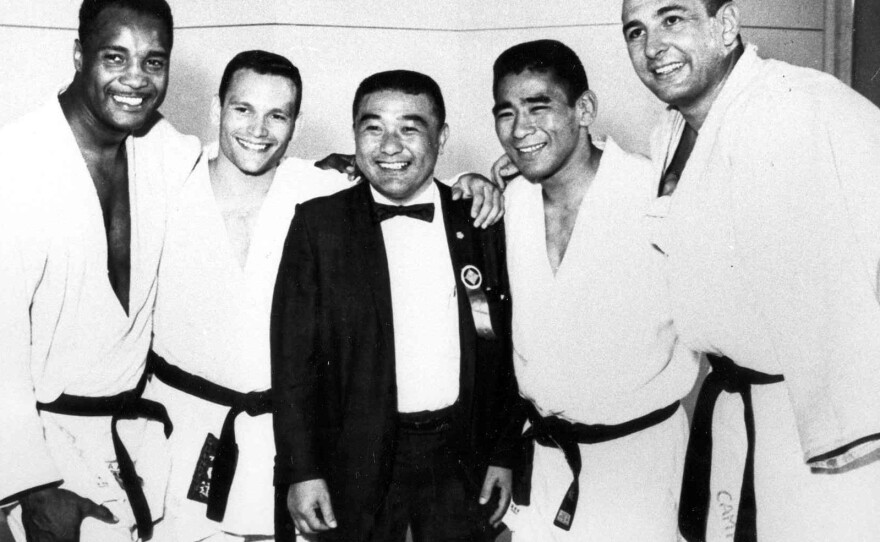

Two decades after the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, judo champion and Colorado native Ben Nighthorse Campbell began a journey that put him in both chambers, where at various times he was able to serve with fellow Olympians Bradley and Ryun.

Campbell says that earning his (judo) chops in martial arts helped in multiple ways when he got into politics.

"Some people say running for office is a form of mortal combat. It can get mean sometimes," Campbell says.

After sustaining countless injuries literally throwing down his competitors, Campbell says running for office was physically easier than an Olympic bid.

But more than being a testing ground for mental and physical tenacity, the Olympics give athletes like Campbell something even more essential in their future bids for office: publicity.

"The thing that athletes get out of their experience is the name recognition and fundraising capability," says David T. Canon, author ofActors, Athletes, and Astronauts: Political Amateurs in the U.S. Congress.

And there's an additional benefit to rigorous training in media exposure at a youthful age.

"You don't get stage fright," explains Campbell.

A High-Profile Sport Helps

With the exception of curling, Olympic athletes tend to be on the young side -- as in under 30 years old. The average senator is roughly 60 years old.

For political purposes, that age lag means two things. First, it provides post-Olympic athletes with plenty of time to get involved in pursuits other than sports. But it also means the public image they created may have faded before they are ready to run for office.

So an Olympic athlete looking to build a political career on their athletic legacy "would have to be a high-profile one -- maybe a gold medalist, or someone who has received a lot of attention," says Canon.

The candidate wouldn't necessarily have to be remembered on a national scale, but just enough to start locally and move up the ranks.

The Enduring Value Of Name Recognition

The milestones along the road from celebrity to politics include a deluge of publicity, followed by encouragement and endorsement by respected local figures.

If you're a former Olympian, your path to Congress might look something like this, ventures Canon: After the Olympics, "You go back to your town. You're the local hero," he says. Time passes. The 10-foot-tall ice sculpture in your likeness has melted, but there's probably a plaque or a sculpture honoring you.

"Then, years later, people are wondering who can run for office," Canon continues. "The rest of us have probably forgotten about him, but he still has that local recognition, which you need to run for a House position."

That's essentially how the story went for Ben Nighthorse Campbell.

He remembers showing up at a county event to support an old friend, who was running for sheriff. Campbell says the meeting coincided with a Democratic search for someone to run for state legislature. When the meeting turned to that issue, someone stood up, looked at Campbell, and said, "Why don't you run?"

Though another meeting attendee insisted the ex-Olympian had two chances of winning -- "little and none," as Campbell recounts the story -- he ran anyway. Campbell went on to serve in the House from 1987 to 1993 and in the Senate from 1993 to 2005.

This year's Olympians

So who among this year's American Olympic contingent might find their way to Congress? None have as yet expressed serious interest in a political career in Washington but a few names would fit the mold.

It would have to be "someone who's had an extended career over a period of several Olympics," says Canon. "Those are the ones who are going to be more in the public consciousness, the ones people will remember 10 years from now. Repeat winners."

That list is fairly short. But it would include someone like Shaun White, the world-famous snowboarder who, despite falling short in 2014, has been the popular face of the sport for years. Skiing stars Bode Miller and Lindsey Vonn (who was forced to withdraw from this year's Olympics due to injury), carry similar cache.

Canon says there's no hard data on what leads athletes into politics, but he guesses that, in the modern era at least, Facebook and Twitter popularity may be a clue that an athlete has at least one of the essential political traits.

Athletes who are comfortable with reporters, who keep their cool during the media crush, he says, would probably have a smoother transition into the political arena than the silent athlete who keeps their headphones on and shies away from the camera.

"The ability to be media-friendly and have a public persona that appeals to people," is an important quality, Canon says. "Shaun White is a great example. He's fun to listen to on television."

As hard as it might be to believe, there might be a politician or two among the chill dudes and shredding babes. Slopestyle skiers Joss Christensen and Sage Kotsenburg, for example, or snowboarders Kaitlyn Farrington and Kelly Clark, have already exhibited some of the traits of successful politicians -- such as determination, theatricality, and comfort in the spotlight.

If that still seems like a stretch, consider the backgrounds of some other athletes and entertainers who also made the jump to politics. Or this unlikely aspiring politician: American Idol star Clay Aiken, who recently announced his own bid for Congress.

If nothing else, the latest Olympians might redefine the traditional victory speech.

Consider Kotsenburg's tweeted response to qualifying for the slopestyle snowboarding finals: "Whoa how random is this I made finals at the Olympics!!!"

Copyright 2014 NPR. To see more, visit www.npr.org.