Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse and Snow White all peer from behind as an elderly Tibetan woman sits in front of the camera. "Do you have any other background?" asks the man who led her to her seat.

"Of course, bring the catalogue," says the weary photographer. He's already taken dozens of portraits that day.

The old woman twirls her prayer wheel as the men flip through the packet. Soon the camera crew lowers a different backdrop, replacing Disney's Magic Kingdom with the historic Potala Palace, where the Dalai Lama once lived.

Almost immediately, the woman gets down on her knee and starts bowing to the image. She refuses to sit back down and face the camera so the photographer has no choice but to change the background.

In the end, the woman — in her red scarf and traditional Tibetan coat — poses in front of a sunny beach with palm trees. The photographer starts counting: "One, two, three" — and the shutter clicks.

That's one of the scenes in Butter Lamp, a fictional short by Beijing director Hu Wei and French producer Julien Feret. Premiering in 2013, the film has won 70 awards. It's now up for an Oscar in the live action short film category.

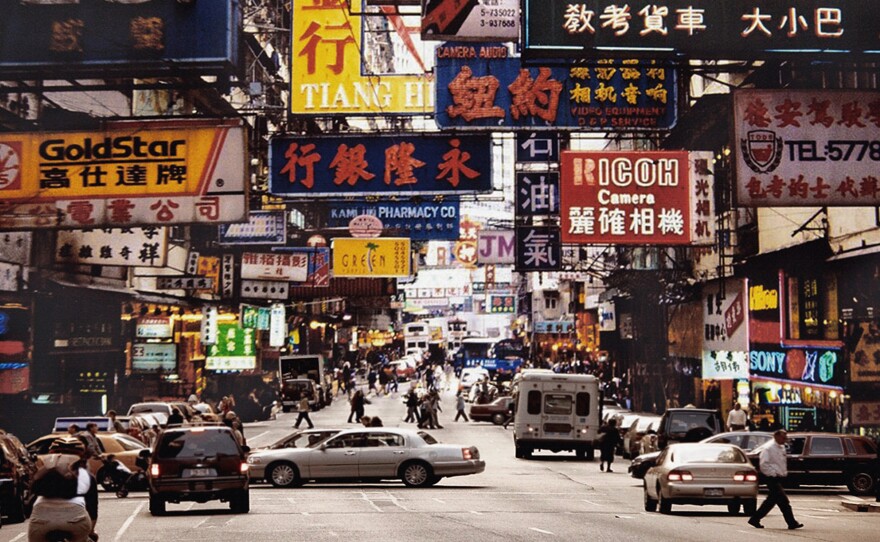

The 15-minute film documents a young unnamed photographer who takes family portraits of Tibetans against backdrops of touristy sites. There's the Great Wall of China, a quaint European country home, Beijing's Olympic stadium.

The name of the film refers to a candle made of yak butter that Buddhists burn to mourn the loss of a loved one. In the film, a young man asks the photographer to bring a butter lamp to the real Potala Palace as an offering to his deceased mother. "But to me it's not just about his mother," Hu told the film blog Indie Wire. "It's also about mourning the culture and traditions that are dying and disappearing."

While there isn't really a plot, Butter Lamp has a clear message about the struggles of Tibetans to preserve their heritage in midst of rapid globalization and modernization.

"[Modernization] is kind of everywhere — in the way they are getting dressed, the fact that they have mobile [phones] and that they can go into the city to work," says Feret, who went to village after village with Hu to scout out locals. "You can also [see] their traditional way of living, like how they pray in the morning."

In each photo, the Tibetans, who are actual villagers and not professional actors, seem out of place and uneasy with the way they're told to pose. At times, when they're asked to wear Western-styled clothing, viewers can clearly see the Tibetans' discomfort. All in all, the film goes through nine backgrounds before the crew pulls the final backdrop up to reveal the actual location of the shoot: a breathtaking view of the vast hills and mountains in the Tibetan region of Sichuan, China, with an unfinished roadway running through.

The idea for the movie was born in 2004, said Hu, when he started visiting nomadic families in a Tibetan village. He visited the village annually over the next three years to take family portraits. Each time the number of families had dwindled, from 20 to 10 to just three. That was the result of a China's "Build a New Socialist Countryside" program, he said. Since 2006, the program has forcefully relocated more than 2 million rural Tibetans to the city.

Feret tells Goats and Soda that he and Hu were (pleasantly) surprised that the film was well-received in China, where officials are sensitive about any media depiction of the complex relation between the government and Chinese-occupied Tibet. The regime has previously banned movies, photos, literature and even celebrities that reference Tibet's call for independence. But Butter Lamp has managed to win several awards in China, including one from the government-run China International New Media Short Film Festival in Shenzhen.

The Oscar nomination was definitely not expected, Feret says. "We have a film that is not really traditional that documents people who may be far from European or American culture."

But they're pleased to be on Hollywood's radar. "It's a tricky subject," Feret admits. "And we always have to fight for the idea that this is a non-political film and that [it's] artistic."

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.