One of the most important American military bases in the world sits in the middle of the Indian Ocean on an atoll called Diego Garcia. It's the largest of the Chagos Islands, a British territory far from any mainland that is spread out across hundreds of miles. Thousands of people, called Chagossians, used to live on Diego Garcia.

The U.S. military moved in in the 1970s only after the British government forced the entire Chagossian population to leave.

For more than 40 years, the islanders have been fighting to return. Now, it seems they have a growing chance.

For the U.S. military, the location of Diego Garcia is perfect: isolated, but with easy access to Africa, Asia and the Middle East. The base was a key staging ground during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The CIA allegedly used it during rendition flights, moving suspected terrorists around the world after Sept. 11.

For the Chagossian people, the islands were perfect for entirely different reasons: abundant fish, a culture of sharing, and a peaceful way of life that lasted generations.

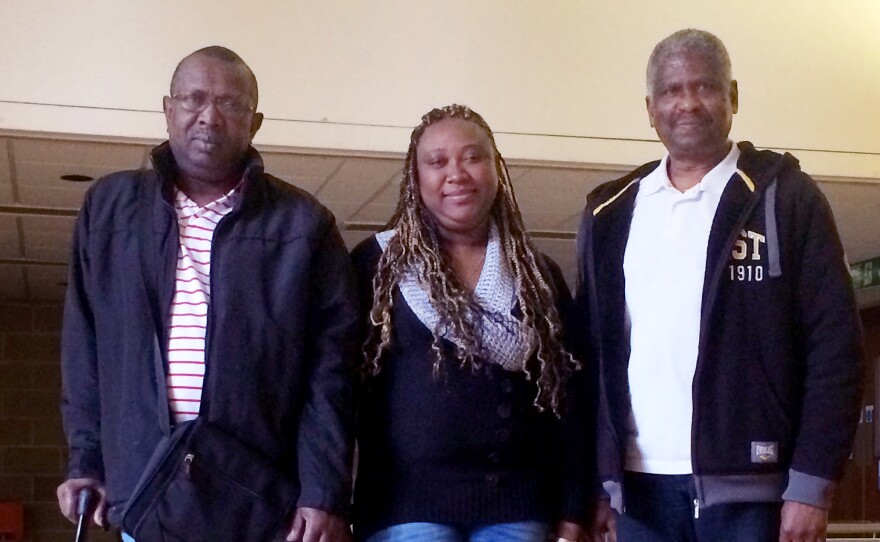

Louis Clifford Volfrin lived on Diego Garcia until he was 10. I met him at a church hall outside of London, where a small group of Chagossians gathered to discuss the latest developments in their struggle.

Volfrin explains that families taught their pet dogs to catch fish for the villagers.

"Our dog would never catch the small fish, only the big ones," he says, speaking in Chagossian patois through an interpreter. "He would catch two, and bring one for us."

In the 1970s, British troops rounded up the Chagossian dogs and gassed them to death. Then they shipped the Chagossian people more than a thousand miles away to Mauritius, a former British colony, where the people lived in abject poverty.

Declassified cables between the British and American governments show a plot to wipe all human life off the islands to make way for the U.S. military base.

"There will be no indigenous population except seagulls," says one cable from 1966. "Unfortunately, along with those birds go some few Tarzans," says another.

"It was a secret deal done between two governments, which resulted in islanders being hoodwinked out of their homes and from their islands," says Jeremy Corbyn, a member of Britain's Parliament who has worked on this issue for decades. "They have sought ever since their right of return."

Sabrina Jean is chair of the U.K. Chagos Refugees Group in London.

"When I been on the island, we say we are in our motherland," she recalls. "Especially when you wake up in the morning, when the elderly told you about the singing of the bird, about the sea — the blue sea. Everything. It was for me a paradise island."

Today, it is difficult to find anyone who will defend the decision to expel the islanders. Many people who represented the British government in the past 40 years now side with the Chagossians.

David Snoxell was Britain's top man in Mauritius from 2000 to 2004. Now he coordinates a parliamentary group working to help the islanders return.

"When I was high commissioner of Mauritius, I sympathized greatly with the Chagossians," says Snoxell. "They did not know it, however, that I sympathized with them. And they did not know that my telegrams to London took their side."

Snoxell says his missives to London were so vehemently critical of the government that he nearly was fired. He believes the reason the issue has not been resolved today is simple bureaucratic inertia — no one in either the U.S. or U.K. government can be bothered to right this wrong.

A decade ago, government officials argued more vocally against resettlement. Back then Bill Rammell, who was then foreign secretary, said return would not be possible.

"They haven't lived in the islands for almost 40 years. There is nothing there. And we would be entering into a financial commitment that would be extremely expensive," he told an interviewer.

Besides the question of cost, there were security concerns about resettlement. The U.S. warned that it could be dangerous to have local people living near the military base.

But British lawmaker Jeremy Corbyn says that rationale doesn't make sense.

"Every other U.S. base anywhere in the world — and there's an awful lot of them — does have communities living quite nearby," Corbyn says. "What's the problem here?"

Even on Diego Garcia, workers from around the world staff the military base.

The U.S. allows 15 Chagossian elders to briefly visit their homeland once a year; a few years ago, Bernard Nourrice was among them. When he arrived on the island of his birth, he says he saw "so many foreigners — like Indonesian, Indian, Mauritian, working with the American base. And there were no Chagossians."

"It's heartbreaking," he says. "I feel so ashamed to see there were no Chagossians gaining their living from the land of their birth, on which foreigners are living happily.

"If the British and the Americans are talking as if they are the champions of human rights, where do the rights of the Chagossian people go, huh? Where does justice lie?"

The U.S. government would not grant an interview about the Chagossians, but a State Department official provided a statement saying, in part: "The Agreement between the United States and United Kingdom on Diego Garcia remains in force until December 30, 2036, unless it is terminated by either party. The United States has no intention of terminating the Agreement, and we have no indication that the U.K. will pursue termination. We refer you to the U.K. Government for further information on issues related to Diego Garcia."

So the U.S. military base is not going to shut down. But there are growing signs that the U.S. might be willing to let some Chagossians return to the land that was taken from them.

A new report commissioned by the British government offers specific proposals for how the Chagossians could return to the islands.

And Snoxell, the former British commissioner to Mauritius, believes this is a breakthrough.

"In view of the study, which showed that there were no real obstacles to resettlement, I think the most likely scenario is that there would be a pilot resettlement or an experimental resettlement on Diego Garcia," he says. "The Americans would never have allowed the U.K. to do a feasibility study which included Diego Garcia if they were against it."

The British government first promised to reach a decision on resettlement by last month, then backtracked.

When asked for comment, the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office provided a statement saying in part that the study "showed that there are still fundamental uncertainties, around how any resettlement could work and the potential costs. Further work is underway to address these uncertainties, to enable a decision on the way ahead as soon as possible in the next Parliament."

That will be sometime after British elections in May.

Momentum does seem to be building in the islanders' favor, though. Last month, a U.N. tribunal said the U.K. does not have the right to make unilateral decisions about a marine preserve on the islands.

That gives hope to people like Luis Clifford Volfrin, whose family was forced off the islands when he was 10 years old.

"If today they say to me I can go," says Volfrin, "I am going."

Until then, he waits.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.