In Detroit, you can snap up a home for just a few thousand dollars these days. But just because a property is cheap, that doesn't necessarily make it a good investment.

Peter Allen with the University of Michigan is equipping local residents with housing investment know-how with the hope that they can go on to revitalize their neighborhoods.

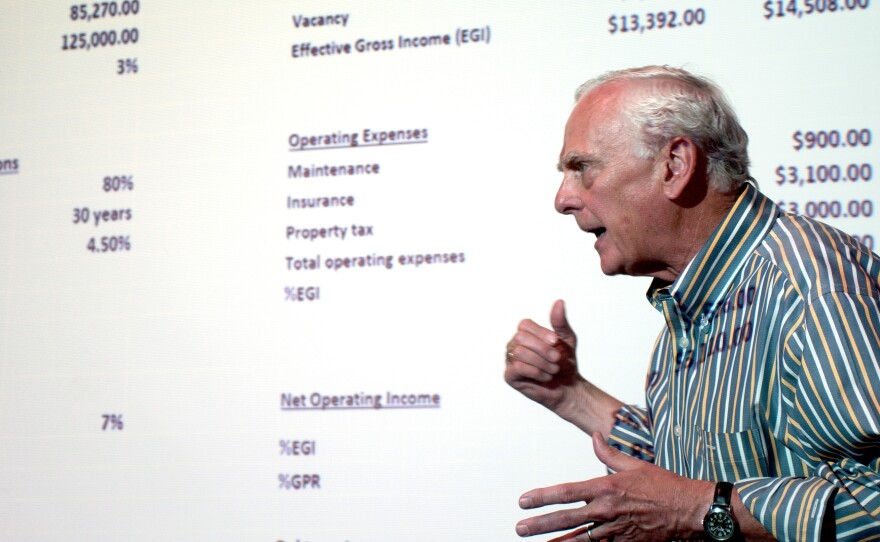

Allen has been teaching a real estate investing course to students in Ann Arbor for more than three decades. This summer, 45 miles east, in Midtown Detroit, he's dedicating his Saturdays to teaching city residents how to also become shrewd investors.

"I crammed this [class] into four weeks for you all, and I was a little sleepless last night," says Allen, standing in front of the classroom.

He's a little sleepless because he's throwing a lot of new terms and principles at his class, pretty quickly.

His 18 students are mostly middle-aged, African-American community leaders. Allen requires them to target a home in Detroit that they could buy, then to work through the numbers.

Lanita Carter stands in front of the classroom showing repair projections for a 900-square-foot house.

"It needs new floors, the plumbing needs to be fixed, the electricity ... ," she says, rattling off a list of repairs.

Her overall estimate is $21,000 in total repairs. Carter bought it last fall for $3,900.

Now, Allen is helping her evaluate if it'd be worth taking out a mortgage for repair costs, briefly living in it and then eventually renting it out.

"So you've got a mortgage payment of $360, you got a tax bill of maybe $50 a month," he says, running through the numbers.

He adds up a few more figures, then reaches the conclusion.

"You've got a rent of $850 and you've got payments that are no more than $600," he says.

That would leave her earning about $250 a month off of a $4,000 cash down payment. He calls that an excellent rate of return.

Allen estimates that he's taught 3,500 students over 34 years in Ann Arbor. He's now in Detroit because he says he wants to help locals revitalize their own neighborhoods through real estate investing.

"This is the best way — individual, grassroots, entrepreneurial, house-by-house, skin-in-the-game approach to neighborhood revitalization than any government program, or city-directed program could achieve," he says.

It's not a get-rich quick class. It's being offered with help from the University of Michigan's Schools of Social Work and Urban Planning, along with the Skillman Foundation, a Detroit organization that helps schoolchildren.

Allen is volunteering his time and says he'd like to continue teaching in Detroit for another five to 10 years.

"I tell the students the only compensation for me is that is when they're finished fixing up a house, they invite me over for dinner," he says.

The students in Allen's Detroit class might be more cautious than the average homebuyer. After all, they are taking a class first.

Consider Dana Hart, a woman in her early 40s. We walked around Detroit's North End neighborhood where she rents.

"My father raised me, and he said, 'Dana, you will never own a home. It can always be taken from you by the bank. It can be taken from you by the city. It's not yours,' " says Hart, who has never owned a home.

She's considering going against her dad's advice because she sees property values in Detroit coming back.

"If you don't own property, you have a likelihood of being pushed out," she says, "and I don't want to be pushed out of this neighborhood."

Hart has her eye on a place with boarded up windows, graffiti and overgrown weeds, but she doesn't see an eyesore.

"I think brick, I think look at the steps and the landings that you can put flowers on, I look at the balcony and I'm like, 'Oh you can sit there and relax,' " she says.

And now she thinks about property taxes, interest rates and the first three first rules of real estate, which everyone knows have to do with location.

"I know how to do, you know, walkability scores and such," she says. "These things that add value to that property, not just the property itself."

She's evaluating proximity to schools, parks, grocery stores and public transportation.

There are some things, though, that are hard to predict in Detroit.

I went to the new home of Lanita Carter, who spoke in class. It's a charming bungalow, at least from the outside.

"It was used as a doghouse. So, that's why, you don't want to go in right now," she says from the front porch. "There were literally seven pit bulls inside this home."

You can still detect the faint odor of canine urine wafting out from inside. The dogs were protecting three squatters who were living there illegally.

Back in the classroom, Peter Allen used this as a teachable moment.

"As you look back on that process could you have improved upon it?" he asks Carter.

She says she would've moved faster. "I bought the house in October and they just got evicted last month," she says.

The squatters did a lot of damage in that time, and she eventually paid a bailiff $2,000 to evict them.

Allen asks if it might've been better to offer them $1,000 to get out.

That might seem like a form of extortion, but ultimately, Allen says, it's really just about being a wise investor.

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.