Back in 1947, Alexander John Haddow made a discovery that didn't seem particularly important.

He was part of a team doing research on yellow fever in Uganda, and he identified a new virus that was making a monkey in his lab sick.

He named the virus Zika, after the Zika forest where his lab was located.

At first, Haddow believed only monkeys were affected. It turns out humans could catch the virus, too, but in Uganda, there have been only two documented cases (although that may be because the symptoms are often mild or even nonexistent).

The Scottish scientist kept detailed records of his research. There were journals, videos, drawings and photographs.

From his records, it's clear that Haddow was not particularly alarmed by the virus. And there were other more dangerous viruses to focus on, like yellow fever.

When he died in 1978, he left his collection of Zika records to the University of Glasgow. The collection was rarely disturbed — until this year, when the Zika virus grabbed international headlines. And so Haddow's archives came into the spotlight.

"After Zika became such a hot topic, it struck a chord with the people in the archive," says Claire Donald, a researcher in the university's Center for Virus Research who is part of a team working to develop a Zika vaccine. "They went through it and found this treasure trove."

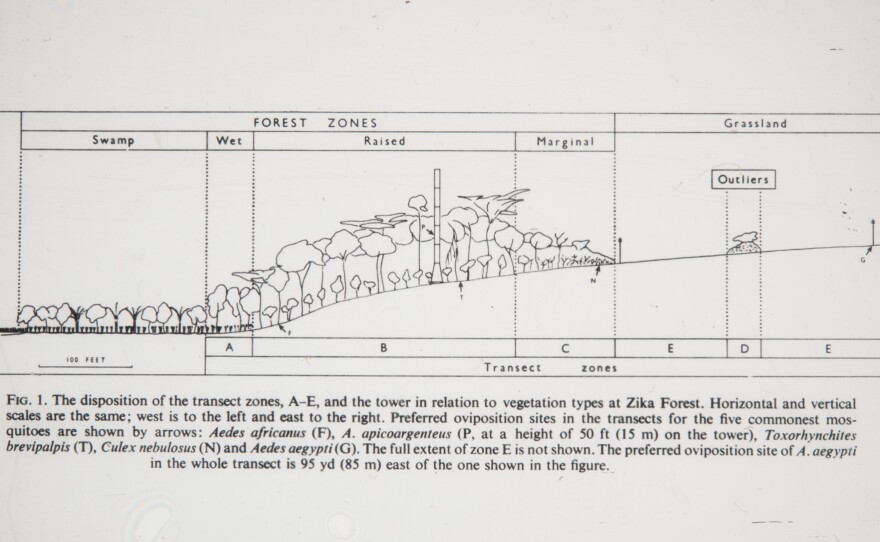

Mosquitoes were a big part of the research. The team daily would capture hundreds of mosquitoes using "human bait" — young boys from nearby communities. The boys would allow the mosquitoes to alight and bite before the scientists would pluck the insects off and drop them into test tubes. The researchers built something called Haddow's Tower — a six-level wooden construction where the "bait" would stand. Haddow would note the elevation at which the mosquitoes were captured, indicating if they swarmed high in the air or near the ground.

They also built platforms in trees for their mosquito "bait" to wait.

The handwriting in the journals that Haddow filled with details and graphs is neat and precise. Because of the old-fashioned style, "I found it a wee bit difficult at first," admits Eleanor Tiplady, a doctoral student in immunology who has just wrapped up a three-month internship dedicated to burrowing through the Haddow collection. "He obviously took great pride in his penmanship."

In 1948, Haddow pinpointed that the virus came from the Aedes africanus species of mosquito. He'd caught the Zika-carrying mosquito on the tree platform.

"That was the key finding," says Donald. Those mosquitoes are "very aggressive daytime biters." And they bite a wide range of animals in addition to humans.

Today, the Aedes aegypti mosquito is the one spreading Zika in Latin America.

"I was struck by the meticulousness of his records," Tiplady says. His science books are crammed with data from the mosquito catches, including how many were captured and where, which species and the time of day.

There are also photographs of the tower — and drawings. Haddow was a talented artist who sketched some of the monkeys infected with yellow fever. Tiplady says she thinks the drawings were mainly for scientific purposes, but he seemed to enjoy sketching and also drew Ugandans in ceremonial headdresses.

Some of the archival material will be displayed at a panel on "Zika Virus: Past, Present & FUture" at the Glasgow Science Fesitval on June 15.

Zika was one of 10 to 15 other new viruses discovered by his team, but most of them haven't been studied. One is the Semliki Forest virus, which like Zika is mild. Another is the chikungunya virus, "which is quite debilitating," she says.

Tiplady says the unearthing of Haddow's archive reminds the world that Africa's jungles harbor many relatively unknown viruses and pathogens. These viruses can remain relatively dormant for years before making a grand reappearance, or morphing from minor irritation into major public-health problem.

"The next Zika," she says, "could be one of the other viruses they discovered."

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.