Reports of diseased and deformed fish at a Carlsbad hatchery run by the Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute are raising questions about the nonprofit’s role in running a proposed fish farm four miles off San Diego’s coast.

The nonprofit partially funded by SeaWorld has been raising white sea bass in Carlsbad for more than 20 years. It’s also planning to build an offshore aquaculture project the size of Qualcomm Stadium’s parking lot that each year would produce 11 million pounds of yellowtail and striped and white sea bass for people to eat. Hubbs would use similar systems for raising fish in each location.

As first reported by the online news site Voice of San Diego, thousands of the Carlsbad fish have come down with diseases, including herpes, or developed blindness or deformities. When fish are deformed, Hubbs often kills them by flooding their tanks with carbon dioxide. When fish are diseased, Hubbs either treats them or kills them.

Some environmentalists say problems in Carlsbad are evidence that the offshore aquaculture project, called Rose Canyon Fisheries, will have the same issues.

Scientists at Hubbs say the concerns with Carlsbad are being taken out of context.

‘Kill the messenger’

Hubbs’ sea bass hatchery program, called Ocean Resources Enhancement and Hatchery Program, is overseen by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. A pathologist from that department is assigned to test the fish for problems.

That pathologist, Mark Okihiro, filed reports on diseases and deformities he found. In May 2014, he wrote an email to his colleagues that said the CEO of Hubbs, Don Kent, was angry with his findings.

“He wishes to have my head mounted on a spike outside the gates of the hatchery as a warning to others who would dare reveal the relevant facts regarding OREHP (Ocean Resources Enhancement and Hatchery Program) and the performance of the Carlsbad Hatchery,” he wrote.

He continued, “The fact is that the OREHP is in disarray and that the program has been going steadily downhill for a decade. Production is down, disease epizootics are up, deformities common place, and the survival of hatchery fish post-release is dismal. Additionally, there are huge ongoing problems with ocular emphysema (gas within the eyes) associated with gas supersaturation, biosecurity, hatchery personnel (skill, experience, turnover), tagging and tag retention, predator attacks at growout facilities, and growout facility care.”

Dallas Weaver, a scientist on OREHP’s advisory committee, said Okihiro was biased against Hubbs. In an online comment left on the Voice of San Diego story, Weaver wrote that Okihiro “had quarantined a major part of the facility with a claim of a ‘possible’ virus (VNN) that could be dangerous. However, he had tested (highly accurate DNA testing) for his suspected virus and the results were negative. He attempted to culture the possible virus with negative results. He then speculated about a possible new virus that affected only a few fish. Again, he had no evidence of a virus … His decision was costing the program 100's of thousands of dollars per month for many months. It's difficult to see his quarantine, if not justified by facts, as having been anything but a big waste of resources.”

Neither Weaver nor Okihiro could be reached for comment.

‘An experimental program’

Mark Drawbridge is a scientist at Hubbs-SeaWorld Research Institute and runs the Carlsbad hatchery. He said focusing on the diseases and deformities doesn’t tell the full story.

Last month, he gave KPBS a tour of the hatchery to demonstrate its process. He peered into a chest-high tank of water at tiny specks flickering under fluorescent lights.

“These are white sea bass, and they’re about 30 days old,” Drawbridge said. “It’s a very sterile environment, they’re being hand fed, and at some point they go into the wild and they’ve got to figure it out, and that’s where the challenge can be.”

Fish die frequently, both in hatcheries and in the wild, he said. No one would expect the thousands of fish born from fish eggs to all make it to adulthood. So focusing on the number of fish that have died doesn’t accurately represent the success of the program, he said.

“If you look at it as the cost per fish that is released, or cost per fish that gets recruited to the fishery, I think you're missing the real picture,” Drawbridge said. “And that is that this is an experimental program. And what we're charged to do is evaluate the feasibility of using this technique to help restore depleted stocks.”

Drawbridge pointed to research that shows Hubbs’ fish have better chances of living than at other hatcheries.

But, he added, their chances aren’t as good as in the wild.

“That's where you want to be, the gold standard,” Drawbridge said.

Michael Kent, a scientist at Oregon State University who studies diseases among farmed fish, said he’d expect there to be diseases and other issues at the start of a hatchery program.

“We almost always encounter challenges with nutrition and disease issues,” Kent said. “Then as the industry matures and methods are improved, these problems become significantly reduced.”

Hubbs is aiming to restock sea bass that are popular among fishermen, and the program is funded by recreational fishing licenses. It’s not wasting taxpayer money when fish die, Drawbridge said.

What’s more, he said, the program is a science experiment meant to constantly improve the hatchery system.

“We haven't taken any steps backwards in terms of what we're doing. All of our steps have been improvements,” Drawbridge said. “At the end of the day, if there's concerns about physical qualities of the fish, I look at the results that are scientifically stamped in the peer-reviewed literature, and I say there's no evidence to support the idea that it's a big concern.”

‘We have heightened concerns’

Matt O’Malley, a lawyer with the environmental nonprofit San Diego Coastkeeper, used to not care about Hubbs’ Carlsbad hatchery. That’s because it is a closed system, so fish waste and other pollutants aren’t supposed to spread to the ocean. Also, the state’s Fish and Wildlife Department oversees its operations and ensures diseases are contained.

Then Hubbs began working on its much larger offshore aquaculture project. O’Malley has long been worried that proposed fish farm would spread disease to wild fish, so the internal documents about the Carlsbad hatchery increase his fears.

“We have heightened concerns now,” he said. “It's like anything. If you're hiring someone to do a job, you look at their resume, look at their past performance.”

Because Hubbs’ process for raising fish will be similar at Rose Canyon and Carlsbad, O’Malley is now paying attention. He put in a public records request for the internal documents that showed the Carlsbad hatchery’s diseases and deformities.

“We know that similar system or management style is resulting in the prevalence of disease, then certainly we have issues,” O’Malley said. “Once you take these fish and put them into a confined system, it actually fosters the type of disease spreading we're concerned about.”

Back at Hubbs, Drawbridge acknowledged “it’s a valid concern” that disease could spread to wild fish, but he said “there are safeguards in place to minimize that concern.”

Hubbs follows a strict procedure in Carlsbad, he said. The fish are inspected by veterinarians several times, including a state fish veterinarian, before being cleared for release. If an infectious disease is found, the fish may be treated, quarantined or euthanized. He also said they do inspections for deformities several times.

“Certain malformations will result in a group of fish being euthanized,” Drawbridge said.

That same process would be used at Rose Canyon: Fish would be tested and examined, and diseased and deformed fish would be killed before they ever made it into the ocean.

Kent, the scientist at Oregon State, said it’s a good sign that Hubbs is screening its fish for diseases, but he said they also should have taken a baseline of the wild population before they began releasing fish. That way they can be sure the fish they’re releasing aren’t spreading diseases, and they would have something to compare their fish to.

“I’m not saying they should stop the project until they do all of this, but it would be optimal to have a good understanding of the underlying pathogens and diseases in these fish beyond just saying they look good and pulling out the fish that don’t look good,” Kent said.

Drawbridge said Hubbs didn’t do a wild fish assessment before it began releasing fish in 1986 from the Carlsbad hatchery. But, he said they do regular wild fish assessments now. And, he said, he can tell the good fish from the bad.

“I don't want to say it's common sense, but a lot of people can look at a fish and say that's a beautiful looking fish, and that's what we're striving for,” he said.

Drawbridge added that several regulatory agencies review Hubbs’ current work, and that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency would oversee the Rose Canyon offshore aquaculture project.

“You can't be abusive because they will come down on you,” he said.

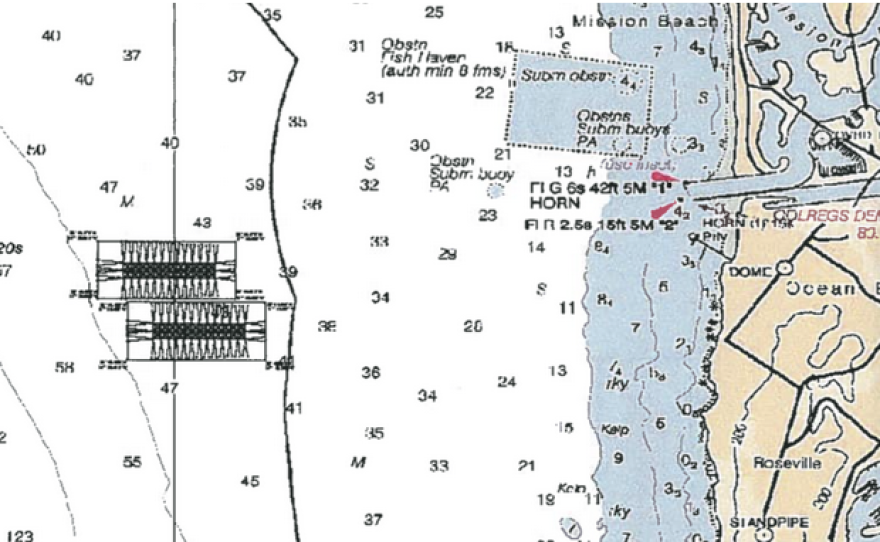

The project would be 4 miles off Ocean Beach, which means it’s in federal, not state waters. O’Malley contends the government won’t have enough oversight of the project.

While there are other fish farms in the United States, this is the first on this scale that would be built in federal waters. That means federal agencies, not California, will have ultimate authority over it. O’Malley said that’s not enough.

“Only two minor permits are required for this project to move forward, and California does not maintain authority over it,” he said.

Last year, it was decided that the EPA would review whether the project follows the National Environmental Policy Act, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration adding input.

O’Malley has submitted a letter with his concerns to the EPA, which is in the process of reviewing the project’s permit.

Other agencies, including the city of San Diego’s water department, the Navy and the California Coastal Commission, also submitted letters. The water department worries fish feces produced from the project could disrupt its wastewater treatment plant in Point Loma.