Guest blogger D.A. Kolodenko examines the Graham Greene novel that was the basis for "This Gun For Hire" as the Noir Book of the Month Club continues in conjunction with the Film Geeks SD Noir on the Boulevard film series.

'A Gun For Sale'

In the 1936 English novel "A Gun For Sale," by celebrated writer Graham Greene, the alienated murderer, Raven — whose hired assassination of a British socialist government minister working in eastern Europe triggers a march toward war — is haunted by his mother’s having committed suicide by slashing her throat, which he witnessed as a child.

“She didn’t even lock the door,” he reminds himself bitterly throughout the story and later in a verbal confession to the novel’s female protagonist, Anne Crowder, as one proof point among the many injustices and failures of humanity he catalogs to justify his murder spree. Likewise, Raven’s nemesis — and Crowder’s fiancé — police detective Jimmy Mather had discovered in his childhood the body of his brother who also killed himself, which leads him to a life of order rather than crime.

These parallel suicides in the back stories of the main characters could feel like a too-obvious conceit to demonstrate how the trajectories of depressed people may be shaped differently by extreme poverty or class privilege. But consider that Greene tried to kill himself several times when he was a young student at the boarding school in Hertfordshire, England where his father was headmaster — once by Russian Roulette; another, an attempt to drown in a swimming pool.

His lifetime of depression informs the way he underpins the contrived plot with deep character insights. Never mind that "A Gun for Sale" was one of his novels that he himself categorized as an “entertainment” as opposed to his serious, literary novels like "The Power and the Glory" (1940), about the persecution of Catholicism in Mexico.

Yes, "A Gun for Sale" is entertaining enough — a suspenseful crime thriller that overcomes its reliance on Woolrichian coincidence and illogic through the sincerity of its author’s compassionate investment in its characters, the quite real and serious political underpinnings, the novel’s manic, dark energy, and a prose style that evokes Dostoevsky in its balance of rich storytelling force with deep social and philosophical investigation. Greene deftly lays bare the in-the-moment minds of his characters: revealing their insecurities, desires, judgments, and self-justifications. It’s breathtaking to read Greene because he deploys the third-person limited omniscient perspective so fluidly that his seamless shifts from character to character can leave you feeling that you’ve been given a God’s insight and empathy — but tempered with a generous dose of cynicism.

Creating the killer Raven

“Patriotism had lost its appeal,” Greene is quoted as saying about his creation of Raven, in W.J. West’s biography, "A Quest for Graham Greene." “It was difficult in the years of the depression to believe in the higher purposes of the city of London or the British Constitution.”

Thus, Raven the working class anti-hero is out to avenge the raw deal he’s been handed by life, not to fight for his country. And, thus, the book’s true villain, the greedy industrialist Sir Marcus, who betrays Raven, was based on real-life, notorious arms dealer Sir Basil Zaharoff, a “plausible villain for those days,” Greene said.

The warning Greene implies — that war profiteers ought to be or are likely to be murdered by the common man — is hardly the stuff of light “entertainment.” And even the main machinations of the plot, according to West, were derived primarily from testimony Greene heard at a 1935 armaments conference, where the question of whether to nationalize the manufacture of weapons led to the grilling of private gun manufacturers, whom Greene described as being unprepared and unforthcoming in the hearings.

One gets the feeling Greene could never have written anything as pure entertainment. After all, according to Michael G. Brennan’s "Graham Greene: Political Writer," in the year he began work on "A Gun for Sale," Greene told his brother, Hugh, that he would rather catch bubonic plague than write another novel.

Heroes and villains

But it’s not just the motivation to take down the crooked gun money-makers that elevates "A Gun for Sale." It would be one thing for the story to be an entertainment qualified with an underlying critique of avaricious capitalism; but it’s not enough for Greene to show us just that the murder of the minister is the catalyst in Sir Marcus’ plot to foment war to cash in on steel production. We need to feel the self-satisfaction and hedonism of Marcus and his lackey as desperate bulwarks to stave off rejection and death. We also need to experience Raven’s rage at his own awful upbringing and at his ugliness from a botched hare-lip operation, which has fostered in him a monstrous, festering resentment, leaving him a loveless “sour bitter screwed-up figure.” It’s Greene’s interest in the destructiveness of villainy to the psyche that anticipates the noir ethos.

By contrast, the courage and perseverance of the nightclub-performer protagonist, Anne Crowder, and of her devoted detective boyfriend Jimmy Mather, read as an unsurprising illustration of British middle-class resolve, and, as in many noirs, the heroes are more sympathetic but less interesting. But Greene sets them on different paths and exposes and thoroughly tests their doubts about each other, lending an extra layer of noirish insecurity to the half of the novel when they’re apart. Greene shows us how easily anyone can die, how easily war can be drummed up for sinister self-interest, and how easily we can lose faith in love, humanity, anything.

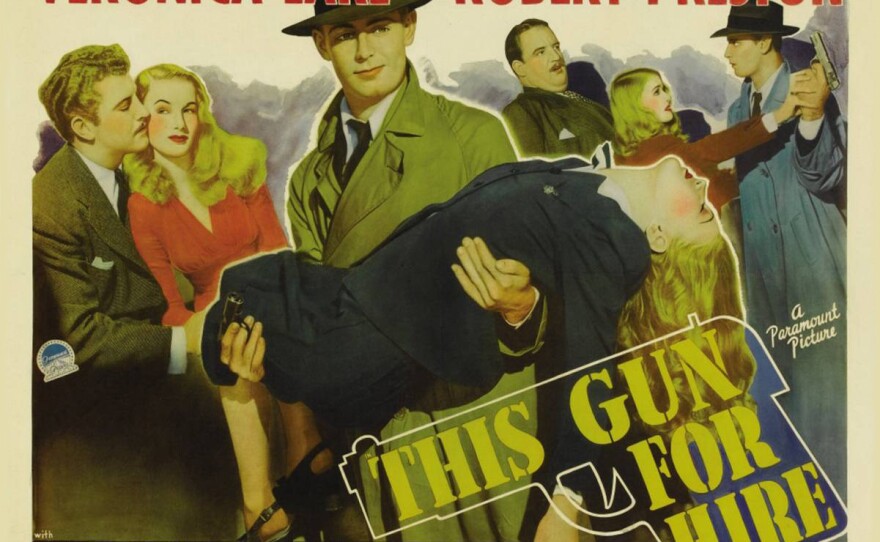

'This Gun For Hire' film

"A Gun For Sale" might have been a different book had it been written a few years later, when post-World War I depression-era anti-war sentiment would lose its wide appeal as the Nazis marched across Europe. The 1942 American movie, "This Gun For Hire," the most famous of the several film adaptations of the book, illustrates not only the Hollywoodification of the novel, but also this different “great war” context: the film transforms the industrialist into a California chemical manufacturer selling out to the imperial Japanese enemy — and Raven not only opens his heart a little to confess his mental anguish to the patriotic Ann Crowder (Ellen Graham in the film, portrayed by Veronica Lake), the only friend he ever had, he also forces confessions from the bad guys and redeems himself by helping in the war effort.

The film preserves the architecture of the novel but lightens up the behavior — the back-story of his mother’s suicide replaced with an abusive aunt, Raven kills, but he no longer sadistically finishes people off at point blank range to watch their heads “shatter like a China doll;” there’s a greater emphasis on his redemptive behavior in the film. And Laird Cregar’s Gates is ridiculously weak and funny in the film, where Willie Davis in the book is a repulsive monster who tries (unsuccessfully) to murder Anne and stuffs her in a fireplace. And of course, Raven’s facial disfigurement in the novel is changed to a more innocuous wrist deformity in the film, to help preserve the compelling onscreen sex-appeal of the similarly featured Ladd and Lake — in the film that made his career and reinforced hers, as they went on to star in six other films together.

The movie is the entertainment that the book claimed to be. The book is as serious, dark, despairing and brilliantly written as anything of the era. And in spite of Greene’s blatant antisemitism — Zaharoff was Greek, but his fictionalized counterpart Sir Marcus must be made Jewish — and some period-typical and equally cringeworthy racism toward Chinese people, Greene’s novel, now overshadowed by the movie, is better than the movie.

Reading along?

Greene was prolific but didn’t create in bursts of inspired activity. He was methodical and consistent, writing in a small black leather notebook with a black fountain pen approximately 500 words each day. When he reached 500, he’d put his pen away and be finished for the day.

Our Noir Book of the Month Club can be just like that: most of the crime novels we’re reading are fairly short. If you read about five or six pages a day, you’ll finish a novel a month. So, if you haven’t started reading along yet, I encourage you to head on over to abebooks.com and pick up an inexpensive reading copy of "A Gun for Sale," as well as any of the novels ahead in our series:

April: "Fallen Sparrow" by Dorothy Hughes

May: "Double Indemnity" by James M. Cain and "Farewell My Lovely" (filmed as "Murder My Sweet" by Raymond Chandler

June: "Fallen Angel" by Marty {Mary} Holland

July: "The Postman Always Rings Twice" by James M. Cain

August: "Build My Gallows High" (filmed as "Out of the Past") by Geoffrey Homes

September: "Pitfall" by Jay Dratler

October: "Gun Crazy: The Birth of Outlaw Cinema" by Eddie Muller

November: "The Big Heat" by William McGivern

December: "Badge of Evil" (filmed as "Touch of Evil") by Whit Masterson

D.A. Kolodenko: Musician. Waiter. Warehouse worker. Print shop manager. College professor. Lecturer. Columnist. Journalist. Editor. Science writer. Advertising copywriter. These are some of the things I’ve been. Detective. Hitman. Embezzler. Boxer. Prison inmate. Fugitive who escapes by running into a tunnel or climbing up something. These are some of the things that the books and movies I like have taught me to avoid being.