Photographer and former San Diegan Alanna Airitam just opened a new solo exhibition, “New Histories: Where Present Meets Past,” at The Photographer’s Eye. The work features several distinct series, including works never before shown in San Diego, and will be on view through March 2. Escondido's 2nd Saturday Art Walk offers extended evening hours from 4-7 p.m. on Saturday, Feb. 10. A reception with the artist is 5-7 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 17.

Airitam's work is otherworldly, not just in the sometimes surreal settings, but in the craft and aesthetics — the mark of her photographer's hand.

"I always thought that I would be a painter, but I never learned how to paint," Airitam said. But her artworks beg to differ. Astonishingly lit and staged, her photography invites leaning in — to check for brushstrokes, or for other proof of unrealness. It's easy to forget it's a photograph. "It's a way for me to paint with a lens."

Airitam's photography challenges racism and representation, about who decides what — and who — is art, and also how society perceives Black bodies in or out of a work of art. In rewriting history, her work is as unflinchingly real, essential and necessary as it is stunning and magical. The symbolism in her work is powerful, but it also shares space with singular beauty.

The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity:

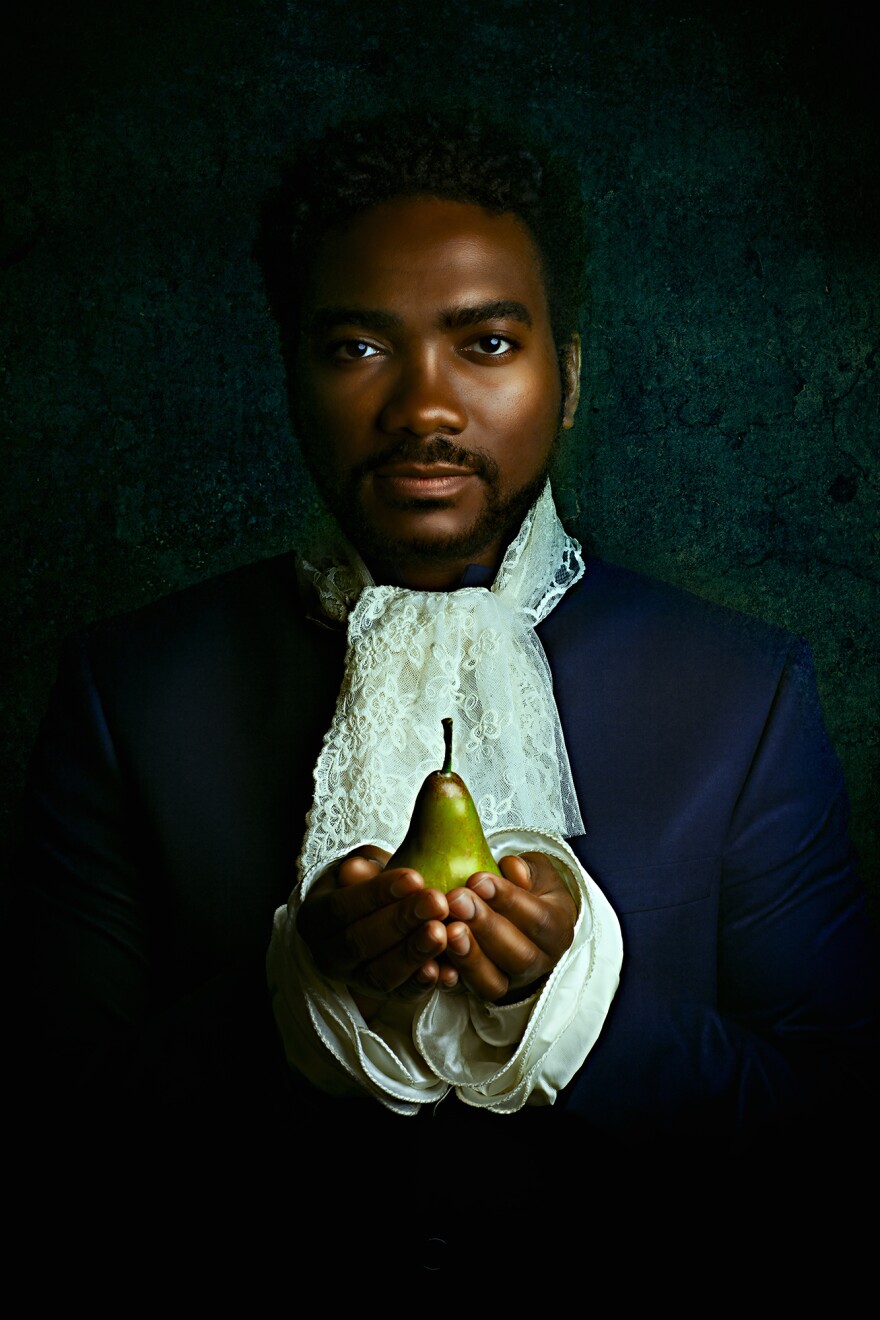

I wanted to start out by having us describe one of your photographs. This is from the Golden Age series and it's called "Dapper Dan." Would you mind telling us what we're looking at here?

Airitam: It's a gentleman, a very striking, handsome gentleman, holding a pear. And he's sort of offering it out to the viewer, you know to the audience, to the person looking. With Dapper Dan and a lot of the other especially male figures in this series, it was really important for me that there was eye contact. He's really looking through the lens, like there's this offering, not just of the pear. There's also this offering of connection.

It really struck me when I was doing this work how oftentimes Black men don't get the respect of being looked at in the eyes. Like, I watch people sort of walk by Black men and like not look at them and I just thought, I wanted to really sort of initiate and sort of force that relationship to happen in this work. It was important to me to do that. So, with "Dapper Dan," as well as the other men in the series, there is a strength about them, but there's also like this softness, right? And it was important for me to make sure that they are multifaceted and not just these one-dimensional figures that our society often puts Black men in.

"He's really looking through the lens, like there's this offering, not just of the pear. There's also this offering of connection. It really struck me when I was doing this work how oftentimes Black men don't get the respect of being looked at in the eyes."— Alanna Airitam

Some of my favorite works of yours are from this series, "The Golden Age," and it's sort of like this powerful opus on representation, because you have Black figures set in almost Renaissance style portraits, the photography is lit and staged just like a painting, these costumes are timeless … Can you talk a little bit about where the idea for the series grew, and why you make these works?

Airitam: That was my first body of work, so it's really interesting to kind of look back on it now, and think about how I relate to that work now, which is very different than when I first created it. I just was feeling very frustrated with everything that I was seeing in the news and the way that I personally was being treated in the corporate America and I think it all just sort of came to this culmination where I felt like I just needed to say something, but I didn't really have a place to say it. So art is really one of those phenomenal and one of the few spaces that we all have available to us where we're able to speak our truth and not be held to that, not be, like, punished for it necessarily. So it felt like a safe place for me to talk about the lack of representation that I was experiencing in my own life, or the way that Black people were being presented through the media. It was a safe place for me to talk about how I hadn't seen myself represented in art spaces in a way that felt powerful and empowering and so I needed to create those things for myself. I was really being — all of us we're being inundated with these messages around police brutality and you know like, watching the targets on the backs of Black people and it really felt for me like I needed to see something different, and I knew that if I needed to see something different, I knew that there were other people that needed to see something different — to a different way to represent Black people in the way that I know Black people to be, you know, beautiful and intelligent and and innovative and you know just big-hearted and have so much to offer this world and I don't feel like we're granted the right to be seen that way often, so I thought I have to make it.

Can you walk us even further back and talk about when you knew you wanted to be an artist and then a photographer?

Airitam: I think I always wanted to be an artist. I was told that's not a viable career, my bank account might agree. But you know, I think I spent the majority of my adult life trying to figure out a way to be creative and get a paycheck at the same time, which is why I went into advertising and I went into the design departments in these ad firms thinking that I can make a difference there. I wasn't seeing Black people represented properly through advertising and marketing and so I thought I could, maybe, be that voice in the room. And I very quickly realized — I was in that career for 20 plus years, but I very quickly realized that I don't have a voice in those places that I still wasn't being taken seriously, even after 20 years. That the suggestions that I had in order to try to make progress wasn't, I guess, money-making or important to these places. Yeah, it really felt like I was hitting dead ends, and also when you're giving your creativity away like that to these institutions, you just don't have it left over for you on the weekends. I think a lot of people think that. I'll go to work and I'll put my energy into this and I'll do something creative in my nine to five and then on the weekends, or at night, I'll come home and make work. And that's really hard to do. And I did it, and I see a lot of other people doing it. For a lot of artists, it's the only way to be an artist — is to hold a job and do it when you can, so I know how difficult that is.

"Photography came a little bit later because I always thought that I would be a painter, but I never learned how to paint and I think that's probably why I make my photography in the way that I do. It's a way for me to paint with a lens."— Alanna Airitam

But yeah, the art bug has always been there. Photography came a little bit later because I always thought that I would be a painter, but I never learned how to paint and I think that's probably why I make my photography in the way that I do. It's a way for me to paint with a lens.

I also, going back into my own personal history, have a lot of interesting threads to the photography world through my mom who worked for Time Life Magazine back in the '60s in the photography department and she worked with people like Gordon Parks and Margaret Bourke-White and a whole slew of amazing photographers that were out there photographing a Civil Rights Movement and everything that was happening in the '60s. And so, you know, she would come home with and this is before my time, because I'm not — I'm almost that old, but I'm not! — But you know, she amassed a collection of books and gifts and stories and photographs from these amazing people that she worked with and I think that there was something that anchored in me around that as a kid because it's just kind of always been there in the background. So photography, yaah, it makes sense.

I want to talk about another series that is represented in this exhibition, called "Ghosts." These are primarily self-portraits and they also push the boundaries of reality and still keep that that painting feeling the timelessness. Can you talk about the series and what you're wanting to say?

Airitam: Yeah "Ghosts" has been really interesting for me to work on. I started it during COVID when I couldn't get people to come over and sit for me and it dawned on me, after being absolutely frustrated and panicky and all the things that happened to artists when they can't work, you know complaining and being in a bad mood. I was like, okay. Well, I guess it's gotta be me. I don't know how long we're going to be locked down, so I guess I gotta do it. It occurred to me that I, as much as I love photographing other people, that it's also a way for me to not have to look at myself, right? Like I can put those stories into someone else and I it's almost sort of fantastical, in that sense like I can create these stories and remove myself away from it. But when you're put in a position where you have to photograph yourself, suddenly all this stuff comes out.

With "Ghosts," I realized that there is this interesting duality that many people have to sort of reconcile with, but most especially Black folks or people of color or anybody from really a marginalized community, where you have to do a lot of code switching in order to stay safe, in order to survive, right? For example, in these corporate settings I can't just go in there and be myself. I have to play the part. I have to be one of the good ones, right, in order to just keep the job and not be targeted. And I feel like that is the case in a lot of different spaces that just don't feel safe or you know, don't feel safe for Black folks to just be themselves. The code switching is real and when you do it so often, you know, I started wondering where do I end and this other personality begins? It's so enmeshed that I found myself really trying to pull it apart during COVID to really deconstruct it and figure out which parts of me are truly me and which parts of me I've had to sort of put on this other hat, in order to get by and be successful and move through the world.

It's been a really interesting process, and quite honestly kind of a painful process to go through this — to really be truthful and honest with myself. This work is, it's very personal. So there's a vulnerability about it and showing it and talking about it that is scary to me.

"It's been a really interesting process, and quite honestly kind of a painful process to go through this — to really be truthful and honest with myself. This work is, it's very personal. So there's a vulnerability about it and showing it and talking about it that is scary to me."— Alanna Airitam

But also I'm moving beyond lens-based work and I'm creating other types of work with this. Like I have a bronze piece in the works. It's a little token from Jamestown. It was a little locker token that you could, I guess, put in at the airport to put your stuff in or whatever and I took this token, and I was able to take out all of the information from the middle part and just leave the top and the bottom part that says "American" at the top and "token" at the bottom. Then, the middle, I changed the wording to "one of the good ones." That's becoming a bronze piece because I feel like I've had to be that person in a lot of these spaces that I found myself, whether it's corporate or the art world, or friendships. I find myself being, sometimes a lot of times, like the only Black person in the room. So I have to be the representative for all Black people in that sense and it's a hard place to be. So it's a really sensitive project and it's the first time I'm showing it here. I feel like I'm showing it amongst family, so that feels sort of safe.

Can you talk a little bit also about another series in the show? It's called "Colonized Foods."

Airitam: Yeah, so again another series that I started during COVID, and this one was just more, a little bit more for fun. It's not as personal or sensitive as "Ghosts," but I was really wanting to sort of break up the self-portraiture that I was doing because that was heavy lifting — with something that wasn't as strenuous, right?

Working with still life is something that I love doing and I was really curious about the foods that we eat and the stories that they hold. I was doing a lot of research and came across some really interesting stories about the foods that we consume and how they have come to our plates and the sort of darker stories that some of them hide like, the wars that had to happen in order for us to have bananas in our cereal in the morning, and how many people have died for that. I think about these things because I think about the hidden history that we're all connected to and how often we don't think about these things. We just sort of take it for granted that these things are there for us.

"I came across some really interesting stories about the foods that we consume and how they have come to our plates and the sort of darker stories that some of them hide, like the wars that had to happen in order for us to have bananas in our cereal in the morning, and how many people have died for that."— Alanna Airitam

I think it's a part of a larger story about how we are, as humans, or maybe Americans, but I think probably humans in general about how we just sort of move through the world very expectantly and, like, things are here for us and we don't have to think about the people who have allowed us to live so freely and luxuriously and conveniently. Like, there's a lot of stuff that had to happen in our past in order for us to be here now, and I think that history and these ties to our past are really important for us to understand and acknowledge, in order for us to move forward into the future in a healthier, more holistic and happier way — joyful way.

Do you feel like there's been movement in the art landscape over the past couple of years, particularly when it comes to works that push the boundaries and talk about race and oppression?

Airitam: Absolutely. I mean, I feel like that type of work's always been there, right? There have been huge movements way before I was in the picture, or a lot of the works that you see in galleries and art spaces now and museums now, like these types of works have been around for a long time.

I think the difference is there's been a lot that has happened, that has created space for us to be able to have these conversations. So we're being we're able to talk about it in a broader sense now. Which is great and I think that Black artists are having a moment where we are being shown a lot more. I do think that on the collection side that hasn't changed very much, and I think that's something that really needs to be remedied. It's not enough that we're being shown in art spaces, but the work needs to be collected. Black artists need to be paid. And the work needs to be in spaces that allow other people to come in and study that work.

"It's not enough that we're being shown in art spaces, but the work needs to be collected. Black artists need to be paid. And the work needs to be in spaces that allow other people to come in and study that work."— Alanna Airitam

I haven't read the most recent report, but there are reports that come out annually around what's happening in the art world, and I know just even up until last year like I'm looking at these numbers and they just have not changed. White men still sit up at the top, and Black women are still at the bottom. So there really still needs to be a balancing of which which artists get to also be collected and appreciated in those ways for over a longer term, historically becoming a part of the canon.

You received the San Diego Art prize in 2020 (announced in 2019). That's an annual award that recognizes excellence in art in the region. And you also recently moved away. What does it mean to bring your work back to San Diego?

Airitam: I'm so happy to be coming back. You know, it wasn't my choice to leave San Diego. I left because I simply could not afford to live there anymore as an artist. You know, I've never really gotten over the breakup, honestly. I love it. I love the community that I formed there. I still have very strong ties to San Diego. My heart is there.

But yeah, it was an honor to win that prize. It made me feel very much appreciated by the city that I love so much. And I love Tucson. I moved here, it took me a while — I'll be honest with you and I moved here in 2019. It was right before we all got locked down and I hadn't really even finished truly unpacking before we were just sort of locked in place and so forming new community and getting out and meeting people and doing all of that kind of stuff didn't really happen until really just last year, and I'm just now getting my footing out here and it's been a wonderful place to be. I feel like it is, in a sense, sort of a sister city to San Diego, and we're not far away so I can make it back to San Diego often enough.

But to bring my work back there — and to bring new work back there and work that I haven't shown anywhere else — feels really special. Like it really honestly does feel like a homecoming of sorts, and very comfortable. I'm really looking forward to being there on the 17th, because I'm gonna get to see so many familiar faces and it feels very comfortable and I'm excited about it. Not that I'm not excited about going to other places, but it's different, it feels more formal when you don't know the space and you don't know the people, right? It really does feel like coming home.