The pandemic has undoubtedly changed the way we work. Gone are the days of clocking in and out at the office every day, as companies and organizations are more comfortable with flexible working situations.

But does the flexibility that comes with working remotely impact men and women differently? According to some economic experts, it could.

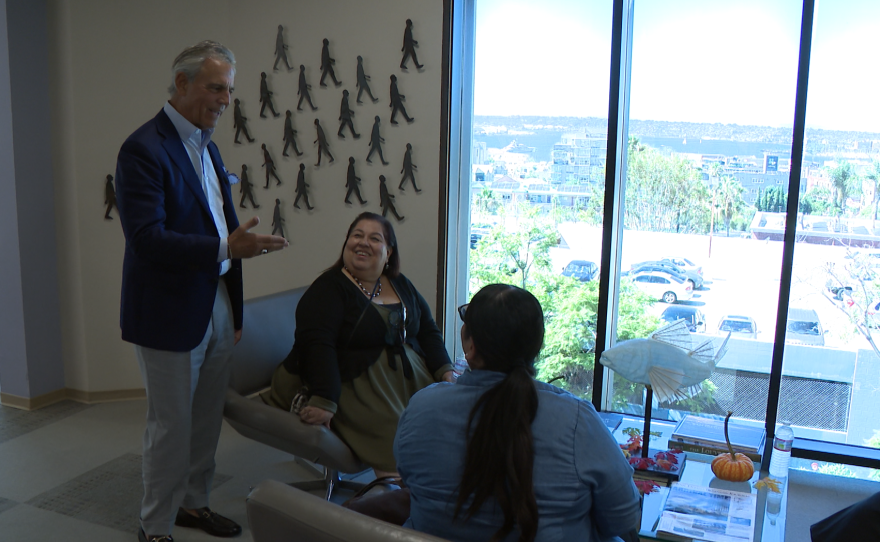

Manpower San Diego CEO Phil Blair lives and breathes employment trends. “We're churning. That's our business, is to churn people. So we see everything in the employment market, good and bad,” Blair said.

He added that in the post-pandemic age, organizations are more comfortable with flexible working hours and locations, allowing companies to keep good employees. But, he said, in-office networking, like so-called “water-cooler conversations,” can be a crucial part of career advancement.

“Where's your bump in the hall where you say, 'Let's go have lunch or join us?’ It's that human nature of knowing people and trusting them. So you have to be visible to do that. On the screen — Zoom or Teams, or whatever — it's not the same,” Blair said.

Recent data suggest men and women aren’t returning to the office at the same rate.

According to a U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics survey released in June 2025, more men are returning to in-person work over women. That survey shows 34% of men worked remotely in 2023, but that number dropped to 29% in 2024. During the same time frame, the share of women working from home stayed largely the same at 36%.

Other data show some women left the workforce entirely because of return-to-office requirements.

'Having a one size fits all approach to management doesn't work'

Elizabeth Lyons is an associate professor who studies organizational and innovation economics at UC San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy. She also co-founded a company, Amplisal, that helps companies with their hybrid and remote work policies.

Lyons said it is not surprising that more women opt for remote work as long as they disproportionately shoulder the burden of non-pay based work, like child or elder care. But she said that lack of visibility could put them at a disadvantage that exacerbates income and wealth inequity.

“The idea that forcing women into office is going to fix this is not the right idea,” she said, “because when that does happen, we're seeing women exit the labor force altogether.”

Lyons said the benefit of remote work is less about location than it is about flexible working hours.

“I don't think it's like this unique moment,” she said. “It's just that if we want to continue the progress that we have been seeing, allowing for individual needs and not taking a kind of blunt force approach to management, I think is important.”

Lyons said managers can personalize work arrangements as incentives. An example would be allowing workers to choose days to come into the office to facilitate interaction.

How to make interactions count

Phil Blair said women have to be more assertive when they are in the office and serendipitous interactions like that “bump in the hall” can be priceless.

“Come in with ideas,” Blair said. “Have a purpose to walk down and talk to my boss about a new idea, or ask how a project's going, or volunteer to do a project. Don't just come in, put your head down, do your work, do a great job, and walk out.”

Lyons added that nonwork interactions, like sending silly videos and finding other ways to ping co-workers, can open doors to those valuable moments, too.

She also said women can be more brave in talking about their accomplishments.

“I know many women, relative to men, are uncomfortable with that. But just doing it and reminding yourself that, you know, if you want to be able to stay in the workforce, manage your competing demands on your time — which is so hard for so many women — speaking up for yourself can support that,” she said. “And so if that can give them some courage to be uncomfortable in that way, I think that's really critical.”

Lyons said there have been no studies showing hybrid work is bad for productivity, yet many studies show it is good for productivity. “So, the productivity-based explanation for not allowing hybrid work, you know, just doesn't resonate. And I've never seen a good explanation for it,” she said.

While the workplace has largely changed from a single-worker type, Lyons and Blair believe it is incumbent on the individual to close the gap in visibility, while enjoying the age of flexibility.