Autumn marks the start of the fishing season in Istanbul, when schools of bonito begin migrating south from the Black Sea via the Bosphorus strait, the busy waterway which bisects the Turkish city. They are met every morning by the fishermen of the ancient coastal city.

The street-cleaning machines are still working the dark, empty roads of this sleeping city when Mustafa Gelgit walks out of the gloom, up to the waterfront in a working-class Istanbul neighborhood called Eyup. The bearded man barely acknowledges his guest, as he steps lightly on board his small, blue-and-white fishing boat, and cranks up the engine.

Gelgit's younger brother approaches in a smaller wooden fishing dinghy, and ties a tow rope to the stern of Gelgit's boat. They don't say a word to each other as they putter away down the Golden Horn, one of the waterways this ancient city was built around. Their backs are to the fat yellow moon, which is slowly sinking behind the Ottoman hilltop cemetery in Eyup.

It's 5 a.m.

Over the clatter of the motor, I can barely hear the pre-dawn call to prayer from Istanbul's waterfront mosques. We putter under two bridges, which even at this early hour are bristling with fishing rods. Sometimes I'm amazed at Turks' addiction to fishing.

For Gelgit, it's a way of life.

The 57-year-old's last name means "tide" in English. He and his two brothers learned the trade from their father, who was also a fisherman.

"The technology has changed a lot since then," Gelgit explains. "First of all there wasn't this much traffic. And also these kinds of motorboats didn't exist. Everything was quite different."

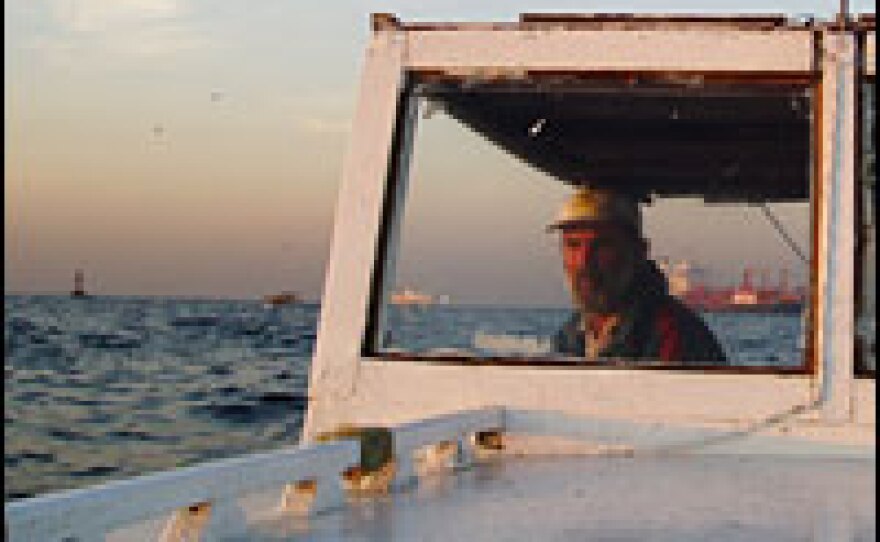

Back in the day, Gelgit's father had to row his boat to work. Today, Gelgit sits in the tiny cabin of his boat, puffing on a cigarette as he hunches over the helm, a comically small wooden steering wheel.

It takes about 45 minutes to reach the much choppier waters of the Bosphorus strait, and we drop off Gelgit's brother along the way. Here, Gelgit drops a long fishing line studded with hooks over the edge of the boat, and begins trolling in circles around the channel.

We start near the European banks of the Bosphorus, a few dozen yards from Dolmabahce Palace, the ornate 19th century home of Ottoman Sultans. Higher up on the hill, stand the neon-lit skyscrapers that are fast becoming the modern face of this sprawling city.

"Fish are like the devil," Gelgit declares at one point. "You see them in one place, then they appear somewhere else. You can never predict where."

After two hours of trolling, the fisherman has only pulled in two palamut, the Turkish name for the breed of bonito that are now migrating from the Black Sea, down the Bosphorus strait to the warmer waters of the Sea of Marmara.

In the meantime the sun has risen, and the waves from Istanbul's water-born rush hour traffic are now knocking us silly. Mammoth oil tankers, lined up in a row, steam north up the Bosporus.

A constant stream of at least four different kinds of ferryboats shuttle east and west, carrying commuters and cars between Istanbul's European and Asian shores. The wake from all of these ships, combined with the fast current, has got our boat as well as a fleet of some 50 similar bathtub-sized fishing vessels pitching madly in the high waves.

"It's actually forbidden for us to fish here," Gelgit admits. "But they kind of tolerate us."

Gelgit leaves the center of the channel, and the palamut to fish by the European shore for a smaller breed of bonito called "istavrit." He has better luck here, pulling in two fish at a time while drifting in the shadow of an eight-story white cruise ship called the Rhapsody.

This fisherman, whose grandfather died fighting in the World War I battle of Gallipoli, exhibits a curious mix of nationalism and religious pride that is uniquely Turkish.

"Eyup is the best place in the world," he says at one point, about the neighborhood in which he grew up.

That pride extends to fishing, which Gelgit says he does seven days a week.

"I like being a fisherman, because I'm my own boss and I can choose my own hours," he says.

Then the fisherman from Eyup drops me off at a ferry landing just a few blocks from my apartment. There's a Total gas station here, right next to the waterfront. I step off the boat, and walk past the cars and gas pumps and convenience store, determined to eat bonito tonight.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))