When Pope Benedict XVI arrives this week in Brazil, he will no doubt recall the stir he made in the world's largest Roman Catholic country two decades ago.

Then, as Cardinal Ratzinger, the Defender of the Doctrine of the Faith, he clashed with Brazil's leading liberation theologian, Leonardo Boff. Ratzinger warned that his teachings conflated Christ's mission with Marxism, which drained Jesus of his divinity and unique role as the son of God.

Ratzinger ordered Boff to be silent for one year in 1985. When the church went after the ordained Franciscan a second time for addressing the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, Boff told Rome: "The first time, I accepted punishment out of humility. Now it is humiliation. That is a sin, and I won't do it."

Boff quit the priesthood but remained a Catholic, pressing for what the 68-year-old theologian, philosopher and author calls the central tenet of liberation theology.

"The opposite of poverty is not wealth – it is justice," he says. "And the objective of liberation theology is to create a more just society, not necessarily a wealthier one. And the great question is, how do we do this?"

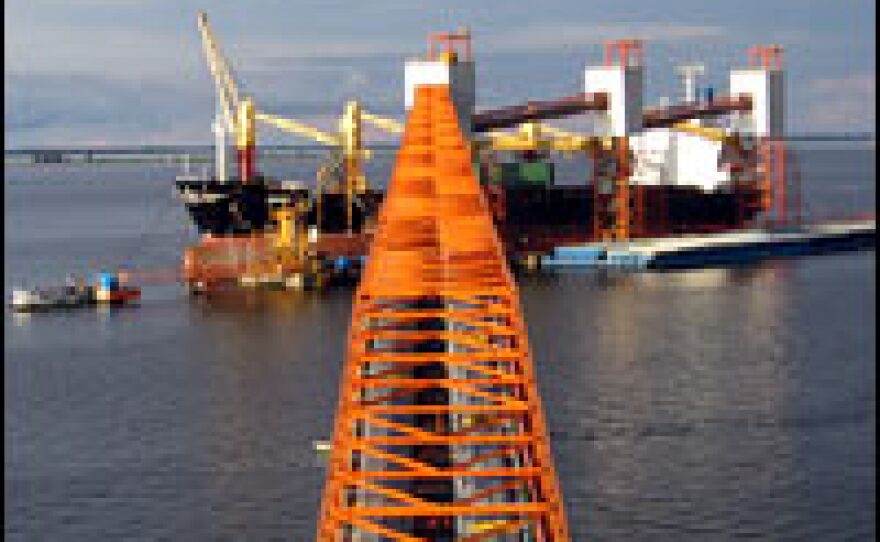

A generation after Boff's rebuke, Brazil's Catholic clergy is actively, at times defiantly, pursuing the struggle for social justice on behalf of the poor: Catholic bishops stage hunger strikes to halt dam projects that they say put profits of big business above the needs of the people. They broker deals with banks to build housing for the homeless. And priests take to the airwaves to denounce the growing footprint of agro-business that has cut down the rainforest to make way for cattle and much-in-demand soy.

Nowhere is that fight fiercer than in the Amazon, home to 23 million people, 43 percent of whom live on less than $2 a day.

Rural Radio, a station owned by the Catholic Church, bristles with debate over the future of the Amazon. Station manager Father Edilberto Sena holds forth on Friday mornings from his corner studio in the Amazon port city of Santarem. Sena's mission is to arouse public action against what he terms the four enemies: logging, mining, cattle-ranching and soy farming.

About 104,000 square miles of trees have been felled in the state of Para, the most deforested in the Amazon according to new government data. Sena refuses to air advertisements of businesses that he says trample the environment, a decision that's drained the station of its coffers, but not this cleric of his zeal.

"Look, look, look – that's timber! " the priest shouts, pointing out a truck laden with logs that he's spotted as he trundles down a pot-holed highway after his Friday show. He's packed visitors into his car for a firsthand look at the deforestation around Santarem. Government satellite imagery shows that in just an eight-year period, from 1997 to 2005, deforestation in Santarem jumped from 30 percent to 40 percent. They say it is impossible to say which is the biggest culprit – soy, cattle-ranching or logging.

As carpets of green rice and fields of soy flash by, Sena's stream-of-consciousness tour inveighs against foreign capital, expounds on the moral decay of the West, and extols Christ as a subversive who fought the status quo.

"Morality is not just about sex," Sena says between exclamations about the next truck filled with timber. "Morality in Jesus' mind means social morality, solidarity, responsibility, ethics – that is morality. And you cannot go to communion on Sunday, and on Monday destroy the forest. It is against the law of God."

Soy farmers and companies who have come to trade in timber and soy in the Amazon argue that their presence represents the kind of development that this under-developed area needs.

If that is what they are providing, Sena asks: "Why, then, is the state of Para 22nd out of the 26 states in Brazil in terms of human development?"

Sena's forthright style has mobilized members of the Catholic laity who organized a recent symposium on the threats facing the rainforest. It drew plenty of environmental groups from civil society, illustrating the interconnectedness of the religious and the secular in the Amazon.

Even the federal prosecutor occupied a prominent place at the assembly. A supporter of Dorothy Stang, the American nun murdered for her defense of the indigenous people's land rights, prosecutor Felicio Pontes applauds the church's work on behalf of the Amazon.

The new Bishop of Santarem says there is "no clear-cut line" between the work of the Church and the work of civil society in the struggle for the rights of people.

"I give the people the power of the word to help them recognize what they should be doing. So it's a path to citizenship — a strong word — and it means the people are going after their own rights," Bishop Esmeraldo says.

Boff, the theologian, says 1 million "Bible circles" in the world's largest Catholic country regularly meet to discuss the Scriptures from the vantage point of liberation theology.

Some 500 miles east of Santarem, Bishop Carlos heads up a new diocese outside the port capital city Belem. He rejects labels, including one that would designate him a liberation theologian. But this bishop with a business sense hurls himself into the politics of the poor, taking their case to halls of power and finance.

It got him the state bank's financing to construct individual homes, modest but well-made, for some 500 people who had been evicted from land they had illegally occupied.

"When you treat the last as being first," he says, "you rescue their dignity and self-esteem."

New homeowner Anderson Gemaque says that "without Bishop Carlos, there wouldn't be dreams."

Harvey Cox of the Harvard Divinity School says liberation theology is thriving in the Brazilian church, and the Vatican is not likely to change it.

"It might make them uncomfortable, but there is not a lot they can do about it," Cox says. "There is an independent streak in the Brazilian church, including the hierarchy, and ... it often takes the form of deep interest and commitment to important issues of social justice. Silencing [priests] doesn't really quell the kinds of current you might like to quell."

That the Vatican is still preoccupied with liberation theology a generation after it held sway over Latin America is evident in its rebuke of the Rev. Jon Sobrino, a Jesuit of El Salvador, who is considered the dean of liberation theology.

Pope Benedict will have ample opportunity on this trip to Brazil to discover how Latin America's clergy sees its mission.

But Boff expects the Brazilian bishops to be model hosts.

"The social injustice is so enormous here that the bishops must answer to the situation," he says. "[But] the bishops never criticize the Pope. They always say he's wonderful, he's for the social justice and the poor. Then they can simultaneously go ahead and do what needs to be done in Brazil. It's the Brazilian way," he says with a smile.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))