In Manila, where housing and hope are in short supply, some people have come up with a novel alternative to their housing woes.

The Philippines capital is crowded and chaotic. It's a city of stark contrasts, where the rich live very well, many in gleaming high rises with stunning views of Manila Bay.

But the vast majority of the 11 million people living here are poor. As much as one-third of the population lives below the poverty line, often squatting in shantytowns, unable to afford anything better.

Manila's North Cemetery offers a respite for some, a place to rest, not just for the dead — but for about 10,000 living, breathing souls who call the cemetery home.

The cemetery, covering more than 100 acres with a main street lined with shade trees and bright pink bougainvillea. The street is kept tidy by city workers who come often to sweep and cart away the trash.

It's vastly different from some of the dirty, crime-infested slums nearby, though electricity and clean water are a problem here, too. So is learning to live with the dead in close proximity, sometimes in the same crypt.

Clare Ventura, a 28-year-old vendor and mother of three, has lived in the cemetery all her life.

"I've had to teach myself to like living here … because we can't afford to rent a place outside," she says. "And also this is where I have a chance to earn a little bit. You get used to it, and it's a lot safer here than most places outside."

Many families like Ventura's came as caretakers, hired by prominent families to clean the mausoleums and protect them from vandals.

But as Manila's population grew, so did the cemetery's. There are now basketball hoops, fast-food stalls and mini-markets tucked in among the crypts and tombs. Groups send volunteers to teach the children. And there are less-welcome visitors, too.

Boyet Zapata, 42, grew up here and helps maintain tombs for several families. He says spirits from the other side sometimes inhabit his coworkers' bodies. Those spirits are of the newly dead, pleading for God's forgiveness, he says.

Roque Rapon, 60, has lived here since 1960, tending the tomb of former president Manuel Roxas.

"I used to be afraid at the beginning, especially at night," Rapon says. "But I learned to live with it. Now, I'm more afraid of the living than the dead because some of the new people are drug addicts and criminals who try to break into the tombs and steal gold or jewelry from the dead."

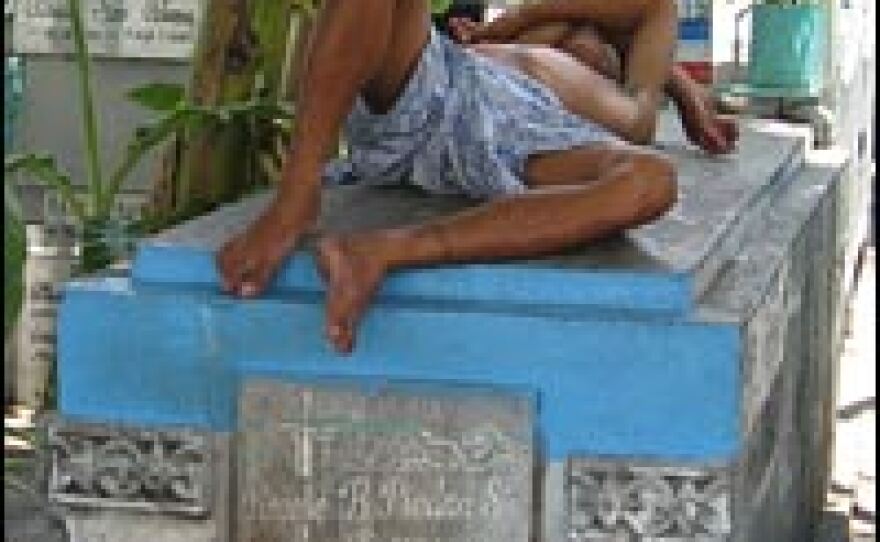

This used to be a nice place to live, he says, a sentiment echoed by 31-year-old Christopher Fernandez, who seems embarrassed by several men gambling atop a nearby tomb.

"I wish these newcomers would go away," Fernandez says. "They're giving us a bad name. They play cards or sleep on the tombs. They walk around without their shirts on. They have no respect for the dead. They have no sense of shame."

And the actions of these few may have ruined it for the majority. Manila Mayor Alfredo Lim says there have been numerous complaints recently about criminals intimidating visitors. Lim is sympathetic to the squatters' predicament, but says he has no choice but to ask them to leave.

"We have to respect the dead," Lim says. "How could they rest in peace when people are drinking and fighting each other … scaring people, those who would like to visit their dead? It's not a nice environment, so we need to restore order. Being poor or being in poverty is no justification for violating the law."

Back at the cemetery, Fernandez mixes the cement he'll use to seal the tomb of Danilo Abad, laid to rest just a few minutes earlier.

The dead man's brother Jun says he has no problem with the laborer and his neighbors living here. If they help keep an eye on his brother, he says, why not?

Fernandez, meanwhile, says he would love not to live here.

"Of course I'd like to leave," he says. "I'm 31 years old. I've already grown old here. But that doesn't mean I want the same thing to happen to my children."

The problem, he says, is they have nowhere else to go.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))