Karachi is one of the world's most populous cities and getting more crowded all the time. New neighborhoods are being built as quickly as people can pour the concrete.

Near the farthest reaches of the Pakistani city, a cement mixer hums and spins in a dusty lot. A workman drops some of the concrete into a wheelbarrow. He then dumps that load into a metal frame and pulls down a handle. A steel mold stamps out eight concrete blocks for one more Karachi home.

Many of these neighborhoods are built illegally on vacant land. Millions of people find homes this way. They generate an entire off-the-books economy.

A few houses are under construction on this barren patch of desert. An Urdu-language banner advertises a model home for the equivalent of $5,000. A look inside one of the houses reveals a two-bedroom home with a tile-floor washroom.

Before long, hundreds of houses likely will squeeze onto this dusty parcel of land in the desert. They're built of a few simple materials, most of which can be purchased from a single dealer nearby.

You could think of it as a sort of extralegal Home Depot. What it's called locally is a "thalla," and the boss is called the "thallawalla."

The boss of this thalla is named Wahab Khan, and he was dropping off a truckload of concrete blocks from his store.

Khan is a newcomer to Karachi. He hails from northern Pakistan, in the tribal areas near the border. Half his family still lives there.

Two years ago, he joined the other half of the family as they moved to the city. Now, he rents a tiny patch of dirt by the road, where he has set up a cement mixer.

Khan's employees are rural men who came to Karachi just a few months ago. They live under a little thatch roof a few feet from the cement mixer. The concrete blocks cost the equivalent of 14 cents each. A bag of mortar costs about $4.

Throw in some concrete roofing material, hire some workers for about $3 a day, and you're on your way to building and selling a house.

Because most locals have no money saved, everything is sold on credit. The electricity, at least, is free. Khan demonstrates how nearby power lines are tapped and how those taps are temporarily removed when government officials visit.

When asked about the danger of using hooks to tap into the lines illegally, he says, "What can we do? We have no choice."

Because the whole system is outside the law, builders here say they also have no choice in another matter. They say that police, who have a way of dropping by, will threaten to tear down an illegal house unless they're paid a few dollars.

Occasionally, a whole construction crew will be thrown in jail. It takes a couple hundred dollars to get them out.

The provincial police chief, Inspector-General Muhammad Shoaib Suddle, was not surprised to hear the claims that his men take protection money.

"Of course we all understand that without protection, these things cannot prosper," he says.

The inspector-general says he recently suspended three mid-level officers for their alleged involvement in land deals. It's widely assumed that corrupt officials play a role in most of these deals.

The illegal housing system in Karachi has its defenders. A leading urban planner says millions of poor people who otherwise might be homeless find shelter this way.

Still, the new settlements have caused some anxiety. Many of Karachi's new arrivals have come from the north — from the area bordering Afghanistan, a region that supports the Taliban.

Karachi's mayor, Syed Mustafa Kamal, considers these ethnic Pashtuns a threat. In his eyes, they are plotting to take over the city.

"These Pashtuns means like fundamentalist — religiously fundamentalist, religiously extremist," Kamal says. "They are coming in. When it comes to ethnicity, when it comes to Islam they all are ... the same."

The mayor gives a tour of the area, driving past squatter neighborhoods and Islamic schools. He passes the area where the journalist Daniel Pearl was found slain. And he points out the window at a bearded man.

"The man who's coming in front of you ... look at him, look at his face," Kamal says.

The mayor says he is convinced that Pashtuns are planning the locations of the illegal housing settlements. He says they are choosing strategic spots that block his own plans for the city.

"It's a very strategic location, you see?" Kamal asks. "The superhighway is there. They can control the whole highway. ... They had a master plan before me. And they definitely have a master plan."

Speaking with several residents of the city's new settlements, it's clear that not all are Pashtuns. And they seemed to have no master plan beyond their next meal.

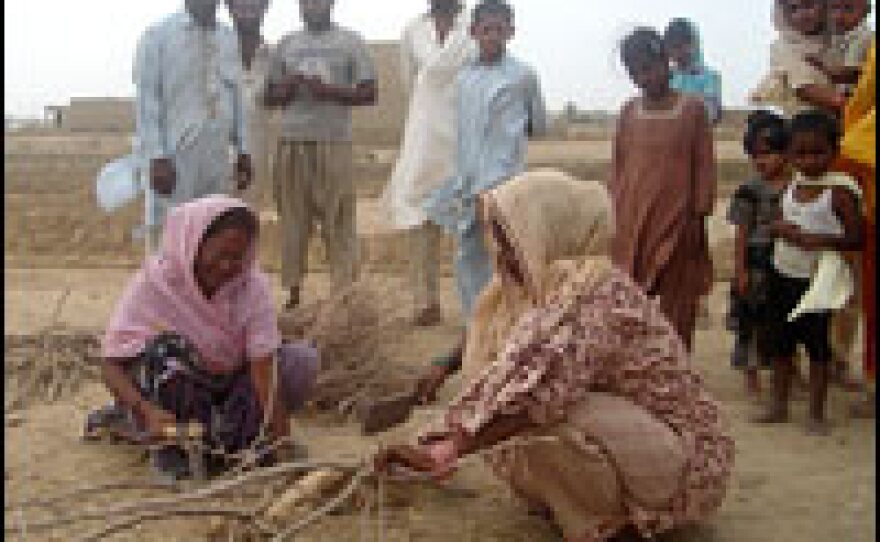

Two of the first residents in the desert neighborhood were outside on their knees cutting firewood. They hacked it out of scraggly bushes they'd found.

Shinaz Begum and Razia Begum live side by side with their families. Between them, they have 16 children, none of whom goes to school.

Their husbands are a fisherman and a fruit-drink vendor. Both women work cleaning houses, and they each earn about 2,500 Pakistani rupees per month, equivalent to $37. The monthly installment on each of their houses is 2,000 rupees, or just under $30.

Look at our children's faces, they say. Don't you think they're underfed?

Even so, the women say their precarious existence on this sandy lot in Karachi is better than their past circumstances.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDAzMjM2NDYzMDEyMzc1Njk5NjAxNzY3OQ001))